Alabama Power Company

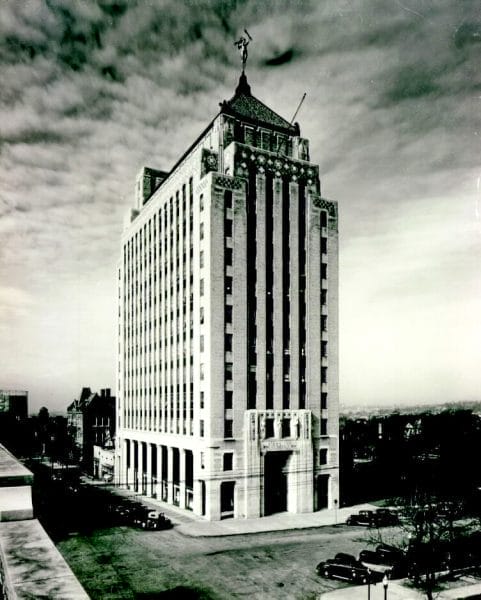

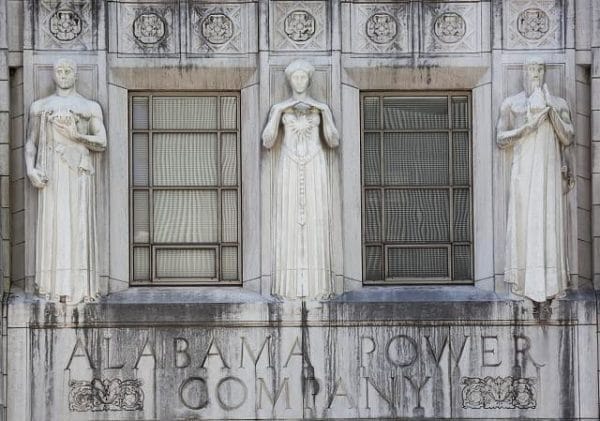

Alabama Power Building, 1925

Alabama Power Company is the largest, oldest, and historically the most significant state utility. Founded in 1906, the company established the first central station generation and transmission system in Alabama. The company’s development is inextricably entwined with the history of Alabama and has been on the leading edge of economic development issues for most of its history. Alabama Power built the first large hydroelectric dam in Alabama and was sending electricity to the Birmingham industrial district by 1914. The company’s ownership and subsequent donation to the federal government of its dam site at Muscle Shoals on the Tennessee River during World War I threw Alabama Power into the middle of a national debate over public versus private generation and transmission of electricity. In the World War II era, Alabama Power lobbied to locate defense industries and military bases in the state and after the war encouraged the conversion of these facilities to peacetime use. Sometimes identified as one of the Birmingham “Big Mules,” (Gov. Bibb Graves‘s term for large corporations in the state’s business center), its policies were often at odds with other big businesses, such as its recruitment of industry into the state, which was opposed by some industrialists who were concerned that labor competition might lead to increased wages.

Alabama Power Building, 1925

Alabama Power Company is the largest, oldest, and historically the most significant state utility. Founded in 1906, the company established the first central station generation and transmission system in Alabama. The company’s development is inextricably entwined with the history of Alabama and has been on the leading edge of economic development issues for most of its history. Alabama Power built the first large hydroelectric dam in Alabama and was sending electricity to the Birmingham industrial district by 1914. The company’s ownership and subsequent donation to the federal government of its dam site at Muscle Shoals on the Tennessee River during World War I threw Alabama Power into the middle of a national debate over public versus private generation and transmission of electricity. In the World War II era, Alabama Power lobbied to locate defense industries and military bases in the state and after the war encouraged the conversion of these facilities to peacetime use. Sometimes identified as one of the Birmingham “Big Mules,” (Gov. Bibb Graves‘s term for large corporations in the state’s business center), its policies were often at odds with other big businesses, such as its recruitment of industry into the state, which was opposed by some industrialists who were concerned that labor competition might lead to increased wages.

Early Years

William Patrick Lay

The Alabama Power Company was incorporated in Gadsden, on December 4, 1906, by Cherokee County native William Patrick Lay. At the beginning of the twentieth century, Alabama was an agricultural state with little electricity-generating capacity and no transmission system. Some Alabama cities and towns generated a small amount of electricity from isolated mostly coal-fired dynamos that operated street lights, occasional street cars, and some residential lighting. A few industries had generators for lights or motors. In 1907, Lay secured congressional approval for the construction of a dam on the Coosa River at the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Lock 12 site, but he was never able to secure money to build the dam. In 1912, he sold his company and its assets, which included only the dam site at Lock 12, to James Mitchell, a Massachusetts engineer with connections to a London investment house. Mitchell founded a holding company, Alabama Traction, Power & Light, Ltd., in Canada to facilitate moving British funds to Alabama banks and hired Montgomery attorney Thomas W. Martin as general counsel.

William Patrick Lay

The Alabama Power Company was incorporated in Gadsden, on December 4, 1906, by Cherokee County native William Patrick Lay. At the beginning of the twentieth century, Alabama was an agricultural state with little electricity-generating capacity and no transmission system. Some Alabama cities and towns generated a small amount of electricity from isolated mostly coal-fired dynamos that operated street lights, occasional street cars, and some residential lighting. A few industries had generators for lights or motors. In 1907, Lay secured congressional approval for the construction of a dam on the Coosa River at the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Lock 12 site, but he was never able to secure money to build the dam. In 1912, he sold his company and its assets, which included only the dam site at Lock 12, to James Mitchell, a Massachusetts engineer with connections to a London investment house. Mitchell founded a holding company, Alabama Traction, Power & Light, Ltd., in Canada to facilitate moving British funds to Alabama banks and hired Montgomery attorney Thomas W. Martin as general counsel.

On Martin’s advice, Mitchell purchased the assets of several companies that held prime dam sites on Alabama rivers, including the Alabama Interstate Power Company, which owned a site at Cherokee Bluffs on the Tallapoosa River as well as the Muscle Shoals Hydro-Electric Company, which owned a site on the Tennessee River at Muscle Shoals. Mitchell opened an office in Montgomery’s Bell Building in early 1912. He acquired the Alabama Power Development Company, which had a small dam and generating facility at Jackson Shoals on Choccolocco Creek, a transmission line to Talladega and Gadsden, and a steam plant under construction in Gadsden. That same year, 1912, Mitchell purchased other Alabama companies that held property on the Coosa River at Duncan’s Riffle (now the site of Mitchell Dam) and Lock 18 (now the site of Jordan Dam).

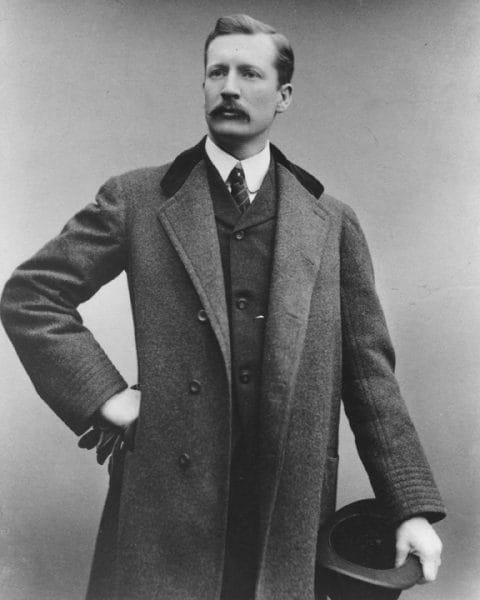

James Mitchell

James Mitchell initially planned to build his first dam on the Tallapoosa River at Cherokee Bluffs (now the site of Martin Dam). In the summer of 1912, Mitchell changed his plans after it became apparent that the Central of Georgia Railroad bridge over the Tallapoosa would have to be replaced. He instead decided to build at Lock 12 on the Coosa and construct transmission lines to Birmingham, the industrial heart of the state, and moved the company headquarters there that same year. The Lock 12 dam (now Lay Dam) was completed in December 1913 and was generating electricity by April 1914 and transmitting it to Birmingham by July. The company’s coal-fired Gadsden steam plant provided backup generation when water levels in the Coosa River were too low to generate electricity.

James Mitchell

James Mitchell initially planned to build his first dam on the Tallapoosa River at Cherokee Bluffs (now the site of Martin Dam). In the summer of 1912, Mitchell changed his plans after it became apparent that the Central of Georgia Railroad bridge over the Tallapoosa would have to be replaced. He instead decided to build at Lock 12 on the Coosa and construct transmission lines to Birmingham, the industrial heart of the state, and moved the company headquarters there that same year. The Lock 12 dam (now Lay Dam) was completed in December 1913 and was generating electricity by April 1914 and transmitting it to Birmingham by July. The company’s coal-fired Gadsden steam plant provided backup generation when water levels in the Coosa River were too low to generate electricity.

World War I and Industrialization

In 1914, candidates in the Democratic primary attacked the company, making an issue of the foreign money that backed the company’s Alabama investments. Soon after the outcry erupted, the outbreak of World War I cut off the supply of capital from England. In addition, landowners around the Coosa Dam filed suits claiming the rising waters were a breeding place for mosquitoes and were increasing the incidence of malaria.

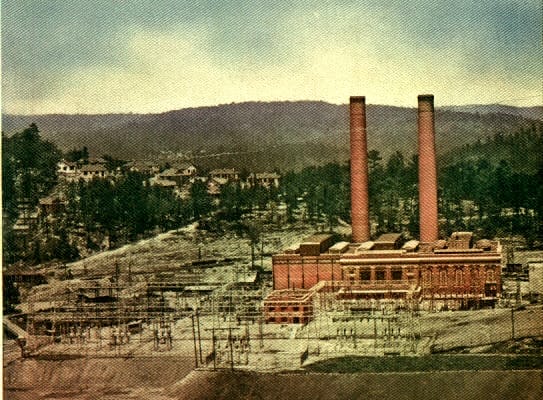

Warrior Reserve Steam Plant, ca. 1920s

At the same time that Alabama Power began generating power, the company also worked to promote industrial development in the state and was responsible for purchasing and placing into production in Anniston the first electric furnace in the South for the manufacture of steel. The demand for electricity in Alabama soared with wartime production, and the company built another steam plant on the Warrior River, a facility later named after William Crawford Gorgas. In early 1917, with U.S. entrance into World War I seeming probable, the U.S. War Department pressured James Mitchell to donate his company’s dam site on the Tennessee River at Muscle Shoals to the federal government so it could produce chemicals for explosives with an ample supply of hydroelectricity. Mitchell chose to donate the site to the government because the federal government threatened to appraise the land at northern Alabama farm rates and confiscate it under war powers. Alabama Power received a $1 check for property that Mitchell and the company had purchased for $500,000. Alabama Power ran transmission lines from its Gorgas Steam Plant to Muscle Shoals to supply electricity for construction of Wilson Dam, which was not completed until 1925, long after the war was over. When the federal government began generating electricity at the plant, Alabama Power was the only utility with transmission lines into the Muscle Shoals area, and it began purchasing power from Wilson Dam and distributing it when needed through connections with Georgia utilities across the southeast as far as North Carolina.

Warrior Reserve Steam Plant, ca. 1920s

At the same time that Alabama Power began generating power, the company also worked to promote industrial development in the state and was responsible for purchasing and placing into production in Anniston the first electric furnace in the South for the manufacture of steel. The demand for electricity in Alabama soared with wartime production, and the company built another steam plant on the Warrior River, a facility later named after William Crawford Gorgas. In early 1917, with U.S. entrance into World War I seeming probable, the U.S. War Department pressured James Mitchell to donate his company’s dam site on the Tennessee River at Muscle Shoals to the federal government so it could produce chemicals for explosives with an ample supply of hydroelectricity. Mitchell chose to donate the site to the government because the federal government threatened to appraise the land at northern Alabama farm rates and confiscate it under war powers. Alabama Power received a $1 check for property that Mitchell and the company had purchased for $500,000. Alabama Power ran transmission lines from its Gorgas Steam Plant to Muscle Shoals to supply electricity for construction of Wilson Dam, which was not completed until 1925, long after the war was over. When the federal government began generating electricity at the plant, Alabama Power was the only utility with transmission lines into the Muscle Shoals area, and it began purchasing power from Wilson Dam and distributing it when needed through connections with Georgia utilities across the southeast as far as North Carolina.

Mitchell died unexpectedly in 1920, and Martin assumed executive authority. That same year, under Martin’s leadership, Alabama Power initiated a rural electrification program and built its first rural line in Madison County. To increase the use of electricity on farms, the company funded research at the Alabama Polytechnic Institute at Auburn and on the state’s agricultural experiment stations to determine how electricity could be used to make farms more profitable and more efficient and improve the quality of life for farmers and their families. In 1920-1921, the company established a New Industries Division and sent a company representative to tour the North and Midwest to recruit industry to locate in Alabama, particularly selling the advantages of less expensive power from hydroelectricity. Economic development would provide more jobs for Alabamians, pump more money into small towns, and increase the company’s industrial electricity sales.

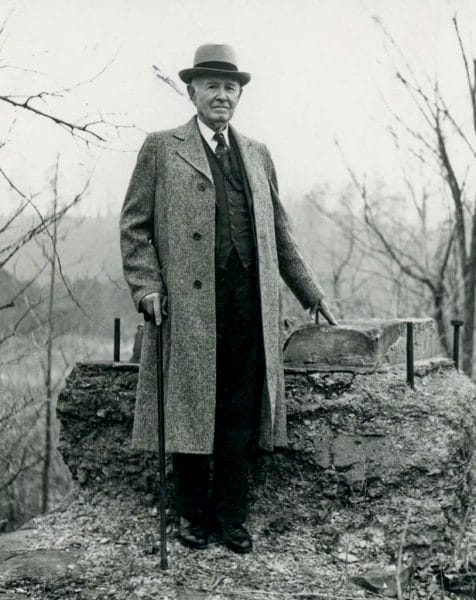

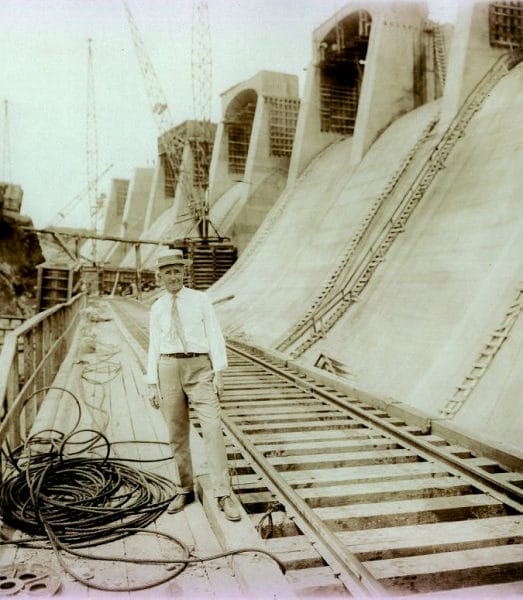

Thomas W. Martin at Lock 18 Site

In 1920, the Alabama State Legislature enacted the Public Utility Act, which was a far-reaching reform effort that gave the three-member Alabama Public Service Commission an increased budget and powers, including the authority to regulate utility rates. After President William H. Taft’s 1912 veto of a bill that would have allowed Alabama Power to build a dam at the Lock 18 site on the Coosa River (where Jordan Dam was later constructed), Congress ceased enacting dam legislation. Alabama Power was unable to build on its other dam sites until Congress passed the Federal Water Power Act in 1920. In the next 10 years, Alabama Power completed Mitchell Dam (1923) and Jordan Dam (1928) on the Coosa River, and on the Tallapoosa River, Martin Dam (1926), Yates Dam (1928), and Thurlow Dam (1930). This additional generation allowed the company to meet the exploding demand for electricity that occurred in the 1920s because of new inventions and the increased manufacture of appliances and industrial motors and equipment. The electric iron was often the first appliance a family would purchase, followed by ranges, refrigerators, and hot water heaters as well as pumps to draw water from wells and provide indoor plumbing for rural homes.

Thomas W. Martin at Lock 18 Site

In 1920, the Alabama State Legislature enacted the Public Utility Act, which was a far-reaching reform effort that gave the three-member Alabama Public Service Commission an increased budget and powers, including the authority to regulate utility rates. After President William H. Taft’s 1912 veto of a bill that would have allowed Alabama Power to build a dam at the Lock 18 site on the Coosa River (where Jordan Dam was later constructed), Congress ceased enacting dam legislation. Alabama Power was unable to build on its other dam sites until Congress passed the Federal Water Power Act in 1920. In the next 10 years, Alabama Power completed Mitchell Dam (1923) and Jordan Dam (1928) on the Coosa River, and on the Tallapoosa River, Martin Dam (1926), Yates Dam (1928), and Thurlow Dam (1930). This additional generation allowed the company to meet the exploding demand for electricity that occurred in the 1920s because of new inventions and the increased manufacture of appliances and industrial motors and equipment. The electric iron was often the first appliance a family would purchase, followed by ranges, refrigerators, and hot water heaters as well as pumps to draw water from wells and provide indoor plumbing for rural homes.

In 1924, Martin folded Mitchell’s original Canadian holding company into a new American company, Southeastern Power & Light, which was incorporated in Maine. Using Alabama Power’s credit and assets, he organized Mississippi Power, Georgia Power, Gulf Power, and South Carolina Power under this holding company. In 1925, Alabama Power built a distinctive art deco‑style headquarters in Birmingham and crowned it with a gilded statue that came to symbolize the industrial revolution brought about by electricity. Over time, she became known as Electra.

The Great Depression, TVA, and Federal Regulation

Thomas W. Martin

The financial success of Southeastern Power and its operating companies attracted Wall Street financiers in 1928 and resulted in a hostile takeover of the company by a group backed by New York banking mogul J. P. Morgan. Southeastern Power & Light was folded into a billion‑dollar holding company, Commonwealth & Southern, which also controlled companies in Tennessee, Michigan, Pennsylvania, Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio. Martin stayed on as president of Commonwealth & Southern but was able to wield little influence because the Midwestern and northern leadership dominated. During these years, Martin maintained his presidency of Alabama Power. The October 1929 stock market crash drastically lowered the value of C&S stock, but the operating companies continued to function despite declining revenues during the Great Depression. In June 1932, Martin resigned as president of Commonwealth & Southern and devoted all of his energies to Alabama Power.

Thomas W. Martin

The financial success of Southeastern Power and its operating companies attracted Wall Street financiers in 1928 and resulted in a hostile takeover of the company by a group backed by New York banking mogul J. P. Morgan. Southeastern Power & Light was folded into a billion‑dollar holding company, Commonwealth & Southern, which also controlled companies in Tennessee, Michigan, Pennsylvania, Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio. Martin stayed on as president of Commonwealth & Southern but was able to wield little influence because the Midwestern and northern leadership dominated. During these years, Martin maintained his presidency of Alabama Power. The October 1929 stock market crash drastically lowered the value of C&S stock, but the operating companies continued to function despite declining revenues during the Great Depression. In June 1932, Martin resigned as president of Commonwealth & Southern and devoted all of his energies to Alabama Power.

In 1932, Franklin D. Roosevelt was elected president of the United States and began to implement his New Deal programs, which aimed to help the nation recover from the social and economic strife of the Great Depression. One program was the creation of the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), a government–funded, public–power corporation. Alabama Power had been supplying electricity to the Tennessee Valley region of Alabama as early as 1912, but when the federally owned TVA began generating power in 1933, Alabama Power could not compete financially and sold its Tennessee Valley assets either to TVA or to newly created municipal power systems. The company lost its profitable Northern Division and had difficulty refinancing its debt to take advantage of much lower interest rates brought about by the Depression. Wall Street investors were uneasy about how far TVA would expand.

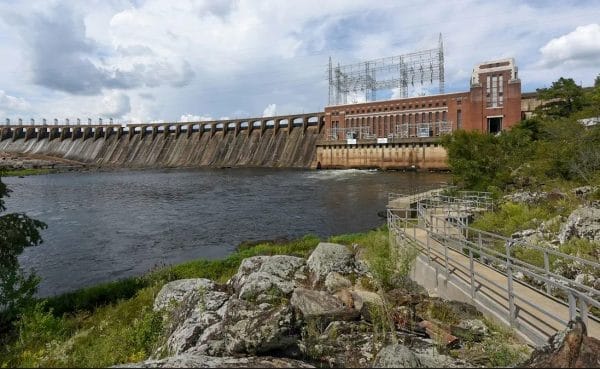

Jordan Dam

The beginning of war in Europe in 1939 and the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 increased federal spending in Alabama on military bases and defense industries. Alabama’s large supply of electricity was one reason the state attracted so many wartime investments. Despite a record‑breaking drought in 1941, Alabama Power was able to provide electricity for war industries, the military, private businesses, and citizens, and was even sending power to aluminum plants in the Tennessee Valley because TVA’s dams and transmission systems were not completed.

Jordan Dam

The beginning of war in Europe in 1939 and the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 increased federal spending in Alabama on military bases and defense industries. Alabama’s large supply of electricity was one reason the state attracted so many wartime investments. Despite a record‑breaking drought in 1941, Alabama Power was able to provide electricity for war industries, the military, private businesses, and citizens, and was even sending power to aluminum plants in the Tennessee Valley because TVA’s dams and transmission systems were not completed.

The 1935 Public Utility Holding Company Act outlawed holding non‑contiguous operating companies, which put Commonwealth & Southern (C&S) in violation. From the mid‑1930s until after World War II, the Securities and Exchange Commission litigated the meaning of the act and its application to the company. The result was a dismantling of C&S and the organization of a new holding company, the Southern Company, which began full operation in 1949 and was allowed to hold only Alabama Power, Georgia Power, Mississippi Power, and Gulf Power. Alabama Power’s president Tom Martin was heavily involved in ensuring that the new holding company was freed from all control by northern or Midwestern financial and utility interests. The 1952 election of President Dwight Eisenhower, who opposed TVA, helped the company achieve congressional repeal of the provision in the 1945 Rivers and Harbors Act that had reserved the company’s upper Coosa River dam sites for TVA expansion. Between 1954 and 1968, Alabama Power constructed five dams and three steam plants, including Logan Martin Dam (1964) on the Coosa River east of Birmingham, Lewis Smith Dam and Lake on the Sipsey Fork of the Black Warrior River near Jasper, and the Barry Steam Plant (1954) north of Mobile. Alabama Power also constructed generating facilities at the Corps of Engineers’ Bankhead Dam (1963) and Holt Dam (1968) on the Black Warrior River and the Miller Generating Plant north of Birmingham (1978). In a major financial commitment, the company built its first nuclear plant on the Chattahoochee River near Dothan in 1977. In 1983 the company completed its most recent hydro facility, Harris Dam on the Tallapoosa River.

The Modern Era

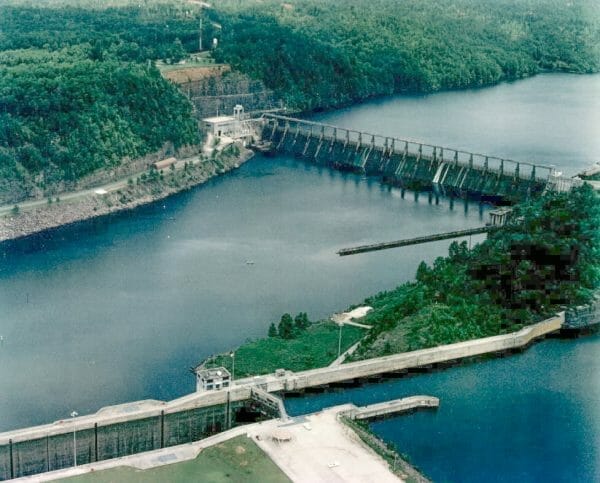

Bankhead Lock and Dam

Through new technology, efficiencies, hydro generation, and economies of scale (meaning that increases in production lead to decreases in price), Alabama Power had managed to reduce its electrical rates between 1913 and 1967. In 1968, however, interest rates and inflation increased so much that the company was forced to request a general rate increase for the first time since the Alabama Public Service Commission began regulating utility rates in 1920. Governor George C. Wallace, who by this time was no longer able to exploit the issue of race to garner political support, opposed the utility for seeking higher rates. The governor’s attacks, which lasted until 1979 and blocked any rate increases, helped drive Alabama Power to the brink of insolvency. Under president Joe Farley (1969‑1989) and his management team, Alabama Power developed innovative ways of maintaining cash flow, such as selling buildings for cash to pay franchise and ad valorem taxes and leasing the building back, leaving vacant positions unfilled, cutting budgets, and deferring non-essential maintenance. These cuts allowed the company to maintain jobs, services to customers, and avoid financial collapse.

Bankhead Lock and Dam

Through new technology, efficiencies, hydro generation, and economies of scale (meaning that increases in production lead to decreases in price), Alabama Power had managed to reduce its electrical rates between 1913 and 1967. In 1968, however, interest rates and inflation increased so much that the company was forced to request a general rate increase for the first time since the Alabama Public Service Commission began regulating utility rates in 1920. Governor George C. Wallace, who by this time was no longer able to exploit the issue of race to garner political support, opposed the utility for seeking higher rates. The governor’s attacks, which lasted until 1979 and blocked any rate increases, helped drive Alabama Power to the brink of insolvency. Under president Joe Farley (1969‑1989) and his management team, Alabama Power developed innovative ways of maintaining cash flow, such as selling buildings for cash to pay franchise and ad valorem taxes and leasing the building back, leaving vacant positions unfilled, cutting budgets, and deferring non-essential maintenance. These cuts allowed the company to maintain jobs, services to customers, and avoid financial collapse.

AM/NS Calvert Plant

In 1983, Alabama Power began to regain a firm financial footing in large part from decisions by the Alabama Supreme Court that the Public Service Commission had to allow adequate rates to cover expenses and a reasonable return on investment. President Elmer Harris (1989‑2001) began to make changes in the company’s infrastructure, organization, and decision-making practices. For example, he gave employees at the district and local levels more authority to make decisions. The company also strengthened its economic development team and supported the organization of the Economic Development Partnership of Alabama, which was jointly founded by Alabama businesses and industries to push economic development in the state. Alabama Power was deeply involved with the recruitment of Mercedes-Benz to Tuscaloosa County. In April 2001, Charles D. McCrary, who had spent his career with Alabama Power and the affiliated Southern Company Services, was elected Alabama Power president and CEO. Since that time, he has continued the company’s efforts in economic development and outreach programs. He led the company in its efforts to attract the ThyssenKrupp (now AM/NS Calvert) steel plant, one of the nation’s largest industrial projects in decades, to the Mobile area. McCrary retired in 2014, and Mark Crosswhite became president and CEO.

AM/NS Calvert Plant

In 1983, Alabama Power began to regain a firm financial footing in large part from decisions by the Alabama Supreme Court that the Public Service Commission had to allow adequate rates to cover expenses and a reasonable return on investment. President Elmer Harris (1989‑2001) began to make changes in the company’s infrastructure, organization, and decision-making practices. For example, he gave employees at the district and local levels more authority to make decisions. The company also strengthened its economic development team and supported the organization of the Economic Development Partnership of Alabama, which was jointly founded by Alabama businesses and industries to push economic development in the state. Alabama Power was deeply involved with the recruitment of Mercedes-Benz to Tuscaloosa County. In April 2001, Charles D. McCrary, who had spent his career with Alabama Power and the affiliated Southern Company Services, was elected Alabama Power president and CEO. Since that time, he has continued the company’s efforts in economic development and outreach programs. He led the company in its efforts to attract the ThyssenKrupp (now AM/NS Calvert) steel plant, one of the nation’s largest industrial projects in decades, to the Mobile area. McCrary retired in 2014, and Mark Crosswhite became president and CEO.

Hydropower, which had been backed by coal-fired generation, was the basis of the company’s first central station system, but by 2007 Alabama Power had switched largely to coal-fired generators, accounting for some 69 percent of output. Nuclear power and natural gas accounted for 19 percent and 8 percent of output, respectively, and hydropower provided 4 percent of the company’s generation. Although seemingly small, this number is significant because it is used for peaking power, the most expensive generation to build because it is used only when the demands for electricity peak on hot summer days.

Alabama Power was involved in conducting studies to protect the environment before there was a Clean Water Act or a Clean Air Act. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, efforts were made to address environmental issues. Through 2008, Alabama Power had invested over $3 billion in environmental controls.

R. L. Harris Dam

Alabama Power Company is an operating company under the Atlanta-based Southern Company, which is the holding company for Georgia Power, Gulf Power, and Mississippi Power. A holding company uses the combined assets of its operating companies to maximize its ability to borrow money and provides certain cost-saving services, which prevents duplication in the operating companies. Alabama Power Company is administrated through six divisions: the Birmingham Division, the Mobile Division, the Eastern Division (with headquarters in Anniston), the Western Division (with headquarters in Tuscaloosa), the Southern Division (with headquarters in Montgomery), and the Southeast Division (with headquarters in Eufaula). In addition, the company has departments that specialize in power generation, transmission, and distribution. Alabama Power currently employs 6,800 people, has total assets of $15.7 billion, and is the largest taxpayer in the state.

R. L. Harris Dam

Alabama Power Company is an operating company under the Atlanta-based Southern Company, which is the holding company for Georgia Power, Gulf Power, and Mississippi Power. A holding company uses the combined assets of its operating companies to maximize its ability to borrow money and provides certain cost-saving services, which prevents duplication in the operating companies. Alabama Power Company is administrated through six divisions: the Birmingham Division, the Mobile Division, the Eastern Division (with headquarters in Anniston), the Western Division (with headquarters in Tuscaloosa), the Southern Division (with headquarters in Montgomery), and the Southeast Division (with headquarters in Eufaula). In addition, the company has departments that specialize in power generation, transmission, and distribution. Alabama Power currently employs 6,800 people, has total assets of $15.7 billion, and is the largest taxpayer in the state.

Today, Alabama Power remains politically active on the state and federal levels, and often on the county and municipal levels as well. As a utility heavily regulated at every level of government, and one of Alabama’s largest taxpayers, decisions made by the Alabama Public Service Commission and legislature, and policies formulated in Washington can have a significant impact on the company’s business. The company thus maintains a strong lobbying presence at the Alabama statehouse. Alabama Power Company has often taken public positions on tax, environmental and energy policy, on education, economic and community development initiatives, and other issues. As for political contributions, the company is prohibited from providing corporate funds to any federal, state or local political candidate, political party or political action committee (PAC). However, its employee-operated state PAC pools dollars contributed by company leaders, as well as the company’s rank and file. Those employee contributions are donated to state political candidates and PACs, but not to candidates for the Alabama Public Service Commission, either directly or through other PACs.

Philanthropic Efforts

Alabama Power Building Detail

Alabama Power has a long history of philanthropy and provides support to United Way campaigns, educational programs, and Project Share, an energy assistance program administrated by the American Red Cross to help low-income families with their energy bills. In 1989, the company established the Alabama Power Foundation using stockholders’ share of profits to streamline and increase the company’s support for communities and improve the lives of Alabamians. By mid-2007, the foundation had awarded more than $100 million to nonprofit organizations across the state. Major programs, among many, have been the Railroad Reservation Park and Red Mountain Park in Birmingham; the auditorium in the Alabama Department of Archives and History‘s new west wing in the state capitol complex; the Maritime Museum of the Gulf Coast, located on the waterfront in Mobile; and A+ College Ready, a national math and science initiative designed to increase the number of students participating in math and science advanced placement courses in high schools throughout the state. Employees and retirees participate in volunteer activities that are coordinated through the Alabama Power Service Organization, founded in 1990. Retirees also performed volunteer work through a company-sponsored group called the Energizers. Together, these groups volunteered more than 100,000 hours of community service in the company’s centennial year of 2006.

Alabama Power Building Detail

Alabama Power has a long history of philanthropy and provides support to United Way campaigns, educational programs, and Project Share, an energy assistance program administrated by the American Red Cross to help low-income families with their energy bills. In 1989, the company established the Alabama Power Foundation using stockholders’ share of profits to streamline and increase the company’s support for communities and improve the lives of Alabamians. By mid-2007, the foundation had awarded more than $100 million to nonprofit organizations across the state. Major programs, among many, have been the Railroad Reservation Park and Red Mountain Park in Birmingham; the auditorium in the Alabama Department of Archives and History‘s new west wing in the state capitol complex; the Maritime Museum of the Gulf Coast, located on the waterfront in Mobile; and A+ College Ready, a national math and science initiative designed to increase the number of students participating in math and science advanced placement courses in high schools throughout the state. Employees and retirees participate in volunteer activities that are coordinated through the Alabama Power Service Organization, founded in 1990. Retirees also performed volunteer work through a company-sponsored group called the Energizers. Together, these groups volunteered more than 100,000 hours of community service in the company’s centennial year of 2006.

The company continues its outreach efforts, and the Renew Our Rivers volunteer cleanup campaign, established in 1999, has grown into the Southeast’s largest volunteer river cleanup program and has received national honors. The company’s Target Zero safety program has reduced employee accidents by 75 percent since 2003 and has been adopted by all Southern Company operating companies. The program has become a model for other utilities across the nation.

Further Reading

- Atkins, Leah Rawls. “Developed for the Service of Alabama”: The Centennial History of the Alabama Power Company. Birmingham, Ala.: Alabama Power Company, 2006.

- Farley, Joseph M. Alabama Power Company: “Developed for the Service of Alabama.” Birmingham, Ala.: Newcomen Society, 1988.

- Jackson, Harvey H., III. Putting “Loafing Streams” to Work: The Building of Lay, Mitchell, Martin, and Jordan Dams, 1910-1929. Tuscaloosa, Ala.: University of Alabama Press, 1997.

- Martin, Thomas W. The Story of Electricity in Alabama since the Turn of the Century, 1900-1952. Birmingham, Ala.: Birmingham Publishing Company, 1952.

- McCrary, Charles D. Alabama Power Company: A Century of Service. Birmingham, Ala.: Newcomen Society, 2006.