National Democratic Party of Alabama

The National Democratic Party of Alabama (NDPA) was formed in 1968 to provide blacks with an alternative to the state’s white-controlled Democratic Party. Although it failed to make significant headway in statewide campaigns, the party did have some local success, and perhaps more importantly, it provided many African Americans with their first experience in politics.

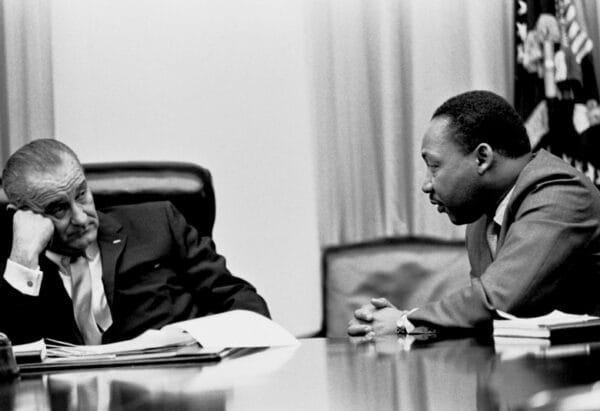

Pres. Lyndon B. Johnson and Martin Luther King

Whites had long dominated Alabama‘s political system at every level, and when Pres. Lyndon Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act into law in 1965, very few African Americans were even registered to vote in the state. Civil rights organizations including the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) quickly began voter registration drives, but despite the increasing liberalism of the national Democratic Party, white leaders at the state level proved unwilling to incorporate blacks into their organization. As a result, many of those blacks who registered in the face of physical and economic intimidation still found themselves excluded from the political process. Frustrated with the continued lack of African American political power, Huntsville dentist John Cashin contemplated a third party that would allow blacks to align with the Democratic Party in presidential elections while providing an alternative at the state and local levels.

Pres. Lyndon B. Johnson and Martin Luther King

Whites had long dominated Alabama‘s political system at every level, and when Pres. Lyndon Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act into law in 1965, very few African Americans were even registered to vote in the state. Civil rights organizations including the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) quickly began voter registration drives, but despite the increasing liberalism of the national Democratic Party, white leaders at the state level proved unwilling to incorporate blacks into their organization. As a result, many of those blacks who registered in the face of physical and economic intimidation still found themselves excluded from the political process. Frustrated with the continued lack of African American political power, Huntsville dentist John Cashin contemplated a third party that would allow blacks to align with the Democratic Party in presidential elections while providing an alternative at the state and local levels.

Cashin, whose grandfather was one of the first black lawyers in the state, was born and raised in Huntsville. He was educated at Fisk University, a historically black institution in Nashville, Tennessee, and after returning from military service in Europe in 1954, he joined his father’s dental practice, which he eventually took over himself. He also became active in politics, particularly with the Alabama Democratic Conference (ADC), a black political league formed by the national party in an effort to bring newly registered blacks into the Democratic ranks. Over time, however, Cashin grew disenchanted with the group’s slow progress and suggested that the ADC reconfigure itself as a third party. He modeled his proposal on the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP), which had mounted serious but unsuccessful challenges to Mississippi’s white Democratic Party in 1964 and 1965.

After other ADC leaders rejected his idea, Cashin split with the group, and on December 15, 1967, he and several others filed for a state charter. They received it less than a month later, making the National Democratic Party of Alabama official. Hoping to convey a connection with the national party, the men requested a donkey as the party’s symbol, but it had already been taken by another independent party, and they settled instead for an eagle. A party symbol was especially important for the NDPA because it would allow those blacks who could not read to identify the party and vote a straight ticket. “Vote Under the Eagle” became a key slogan for the party.

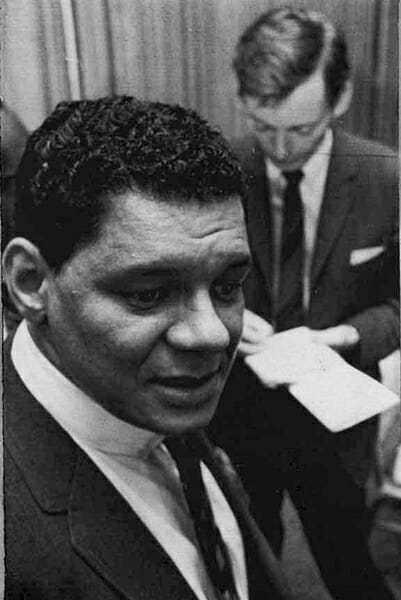

John L. Cashin

Although comprised primarily of blacks, whites—typically upper and upper-middle class—did make up roughly 10 percent of the NDPA’s membership. Exact membership figures are difficult to determine, but in the 1970 gubernatorial election, the NDPA candidate received more than 125,000 votes across the state, indicating that the party had made tremendous strides in the two years since its inception. The NDPA embraced the ideals of the “black power” movement, marking a shift in the methods of civil rights activists in Alabama. Instead of direct-action protests such as marches and sit-ins, which targeted the elusive and intangible goal of “equality,” the NDPA engaged in a political campaign aimed at gaining black control of county and state politics, much like MFDP had done in Mississippi.

John L. Cashin

Although comprised primarily of blacks, whites—typically upper and upper-middle class—did make up roughly 10 percent of the NDPA’s membership. Exact membership figures are difficult to determine, but in the 1970 gubernatorial election, the NDPA candidate received more than 125,000 votes across the state, indicating that the party had made tremendous strides in the two years since its inception. The NDPA embraced the ideals of the “black power” movement, marking a shift in the methods of civil rights activists in Alabama. Instead of direct-action protests such as marches and sit-ins, which targeted the elusive and intangible goal of “equality,” the NDPA engaged in a political campaign aimed at gaining black control of county and state politics, much like MFDP had done in Mississippi.

At the first NDPA convention, held on July 20, 1968, participants elected John Cashin party chairman and adopted the party’s constitution and platform. The platform in particular was quite liberal compared with that of the Alabama Democratic Party (ADP). It called for restructuring the state’s tax system to relieve the tax burden of the working class and promoting industrial development in rural Alabama. The NDPA specifically sought industries that would serve local residents’ needs without exploiting either workers or the environment. The platform also advocated an increase in environmental regulation, a guaranteed right to peaceful protest, and an end to the military draft.

The party first received considerable attention at the infamous Democratic National Convention of 1968 in Chicago, when its representatives challenged the legitimacy of the Alabama delegation, just as the MFDP had done four years earlier in Atlantic City, New Jersey. In their appeal, NDPA representatives presented themselves as Democrats in favor of “political and social justice.” Ultimately, however, the national committee rejected the NDPA’s challenge and chose to seat the ADP delegation. After their unsuccessful challenge in Chicago, members of the NDPA refocused their efforts on local and state politics, particularly in the Black Belt, where a white minority still held political power over a much larger black population.

Rural Greene County became the scene of one of the party’s first major victories, as black candidates won a number of offices under the NDPA banner. When black candidates were left off the Democratic primary ballot by the county’s probate judge, the U.S. Supreme Court held the judge in contempt and ruled that a special election would be held in July 1969. In that election, African Americans swept almost every county post. Nearly four years after the Voting Rights Act, Greene County received national media attention for its electoral gains and black-controlled county government.

Coming off the successes in Greene County, NDPA chairman John Cashin launched a gubernatorial campaign against George Wallace in 1970. He repeatedly challenged Wallace to debate the issues, but Wallace refused. When Wallace pandered to segregationists in the state by calling the election of a black governor the “greatest threat” to the state, Cashin urged Wallace to focus instead on the issues of the campaign. In the end, Cashin received roughly 15 percent of the votes, compared with Wallace’s nearly 75 percent, but the fact that Wallace was forced to acknowledge his presence spoke volumes. Not since Reconstruction had an African American politician spoken so forcefully in Alabama.

Although many of its high-profile candidates were unsuccessful, the NDPA’s county-level gains demonstrated the potential political power of the new black electorate created by the Voting Rights Act. This forced Democratic Party leaders to bring blacks into the political process, lest they risk alienating an entire bloc of new voters. Thus, the NDPA eventually fell victim to its own successes: as blacks showed their political power, the Democratic Party became more inclusive. More than a century after emancipation, blacks in Alabama had finally made their political voice heard. In addition to the NDPA’s local victories in the Black Belt, this was the ultimate legacy of the party.

Further Reading

- Frye, Hardy T. Black Parties and Political Power: A Case Study. Boston: G. K. Hall, 1980.

- Lawson, Steven F. In Pursuit of Power: Southern Blacks and Electoral Politics, 1965-1982. New York: Columbia University Press, 1985.