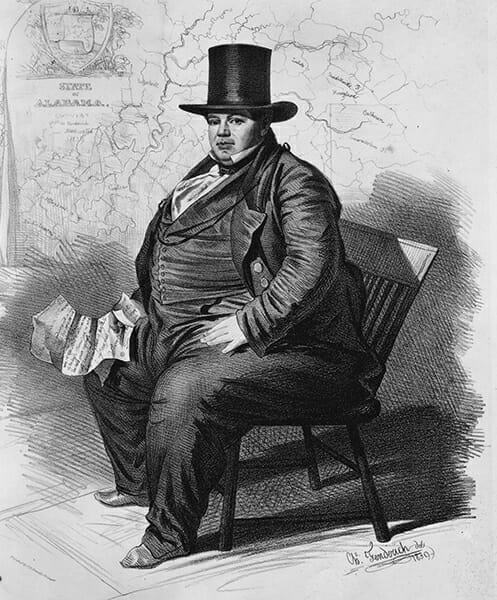

Dixon Hall Lewis

Dixon Hall Lewis (1802-1848) is unfortunately probably best known for his extreme size, but he was also an able legislator who served Alabama in the state legislature and both the U.S. House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate. A gifted orator and politician, Lewis was instrumental in moving Alabama away from its strong position of nationalism at the beginning of the Jacksonian era to a position supporting states’ rights that eventually led to secession.

Dixon Hall Lewis

Dixon Hall Lewis was born on August 10, 1802, in either Dinwiddie County, Virginia, or Hancock County, Georgia, to Francis and Mary Dixon (Hall) Lewis. Lewis graduated from South Carolina College (now the University of South Carolina) in Columbia in 1820 and moved to Autauga County, Alabama, the same year. Lewis became a member of Alabama’s conservative, elite planter class, which supported states’ rights and opposed Pres. Andrew Jackson’s philosophy of a strong centralized government. Lewis read law in Cahawba, was admitted to the bar in 1823 and practiced law in Montgomery. On March 11 of that year, he married Susan Elizabeth Elmore of Autauga County, with whom he would have seven children. In 1826, he was elected to the lower house of the Alabama legislature and was re-elected for two additional terms. In 1828, he was deeply involved with the creation of legislation that would extend Alabama’s jurisdiction over all Native American territory within its boundaries. The bill passed the legislature and it essentially denied Indians rights promised them in treaties with the federal government while protecting the rights of Alabama citizens to settle on lands in the Indian cessions.

Dixon Hall Lewis

Dixon Hall Lewis was born on August 10, 1802, in either Dinwiddie County, Virginia, or Hancock County, Georgia, to Francis and Mary Dixon (Hall) Lewis. Lewis graduated from South Carolina College (now the University of South Carolina) in Columbia in 1820 and moved to Autauga County, Alabama, the same year. Lewis became a member of Alabama’s conservative, elite planter class, which supported states’ rights and opposed Pres. Andrew Jackson’s philosophy of a strong centralized government. Lewis read law in Cahawba, was admitted to the bar in 1823 and practiced law in Montgomery. On March 11 of that year, he married Susan Elizabeth Elmore of Autauga County, with whom he would have seven children. In 1826, he was elected to the lower house of the Alabama legislature and was re-elected for two additional terms. In 1828, he was deeply involved with the creation of legislation that would extend Alabama’s jurisdiction over all Native American territory within its boundaries. The bill passed the legislature and it essentially denied Indians rights promised them in treaties with the federal government while protecting the rights of Alabama citizens to settle on lands in the Indian cessions.

Lewis also served as a member of the board of trustees of the University of Alabama from 1828 to 1831, during the period of its construction. He had an outgoing personality, was liked by his constituents, and was considered an exceptional orator. At the time of his election, he was both the youngest and the heaviest member of the Alabama legislature, weighing in at 330 pounds. Special chairs had to be constructed for his large frame.

In 1828, Lewis was elected as a States’ Rights Democrat to the U.S. Congress and again in 1830 after defeating former Alabama governor John Murphy. During his campaigns, Lewis’s increasing size forced him to travel throughout his district in a vehicle that was specially designed to accommodate his weight. In addition to his special conveyance, Lewis always carried along a large, strongly constructed chair to accommodate his bulk, because standing for any length of time was difficult.

Like many states’ rights advocates, Lewis subscribed to the idea that the Union was a voluntary compact of individual sovereign states. The federal government’s authority was restricted to those powers assigned to it by the Constitution. Since it did not grant authority to the Union to deal with these issues, Lewis was opposed on constitutional grounds to the federal bank, the high protective tariff, and internal improvements made by the federal government. Southerners particularly disliked high protective tariffs, which favored Northern interests at the expense of the South. Tariffs levied on imported goods entering U.S. ports were a chief source of revenue for the federal government until they were surpassed by the income tax in the early twentieth century. High tariffs protected American industries located primarily in Northern states. Southerners exported their cotton and felt that such tariffs hurt their ability to sell it abroad and to buy imported goods.

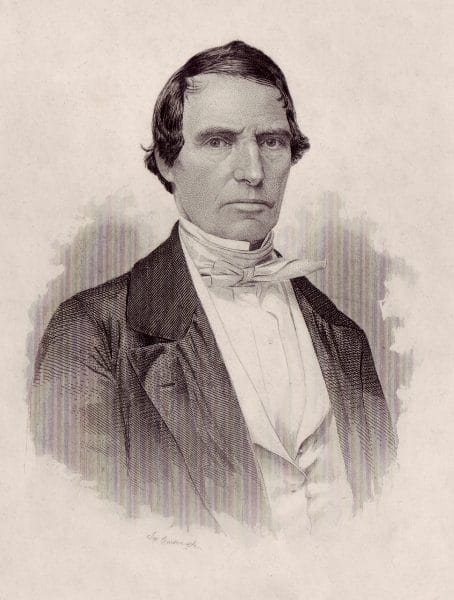

William Rufus King

Lewis chaired the Committee on Indian Affairs for the twenty-second and twenty-third congresses and supported the administration’s policy on Indian removal. He lost the 1832 election, but was returned to the House in 1834 and re-elected for four succeeding terms. After serving out an eighth term, Lewis resigned from the House of Representatives to accept an appointment and subsequent election as a Democrat to the U.S. Senate, filling the seat vacated by fellow-Alabamian William Rufus King, who had been appointed U.S. Minister to France. In the Senate, Lewis chaired both the Committee on Finance and on the Committee on Retrenchment.

William Rufus King

Lewis chaired the Committee on Indian Affairs for the twenty-second and twenty-third congresses and supported the administration’s policy on Indian removal. He lost the 1832 election, but was returned to the House in 1834 and re-elected for four succeeding terms. After serving out an eighth term, Lewis resigned from the House of Representatives to accept an appointment and subsequent election as a Democrat to the U.S. Senate, filling the seat vacated by fellow-Alabamian William Rufus King, who had been appointed U.S. Minister to France. In the Senate, Lewis chaired both the Committee on Finance and on the Committee on Retrenchment.

Weight problems continued to plague Lewis (at his death he weighed at least 430 pounds). Travel from Alabama to Washington was generally difficult under any circumstances but especially so for Lewis. When he was no longer able to travel in his specially designed carriage, he was forced to book two seats on stagecoaches and trains, but even this did not assure comfort or safety. On one trip through Georgia, en route to Washington, the bottom fell out of the stage coach in which he was riding. Variations of this story were told for years in Washington.

Just as he had in Alabama, Lewis ordered a specially constructed chair for his use in the U.S. Capitol. Once settled in it, he tended not to move, but he nevertheless became an influential congressman, well known for his oratory as well as for his good humor and wit. As he attracted increasing attention about his weight, however, his disposition began to sour. Toward the end of his life, he refused to be weighed. His size eventually caused his health to decline, and he traveled to New York to seek medical advice in 1848. While there, his condition worsened, and he died that year on October 25. Lewis’s Senate seat was filled by Benjamin Fitzpatrick. A respected U.S. senator, he was given an elaborate funeral in New York City and interred in Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York.

Further Reading

- Doss, Harriet E. Amos. “Dixon Hall Lewis.” In American National Biography. Vol. 13, pp. 566-568. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Malone, Dumas, ed. “Dixon Hall Lewis.” Dictionary of American Biography. Vol. 11, p. 210. New York: Charles Scribner’s and Sons, 1933.

- Mellown, Robert O. “Dixon Hall Lewis: An Alabama Silhouette.” Alabama Heritage 48 (Winter 1998): 47-48.

- Watson, Elbert L. Alabama United States Senators. Huntsville, Ala.: Strode Publishers, 1982.

- Williams, Thomas M. “Dixon Hall Lewis.” Alabama Polytechnic Institute Historical Studies, 4th series (1910): 1-33.