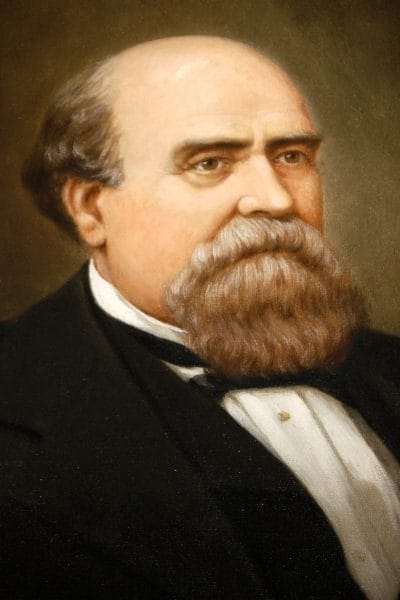

George S. Houston (1874-78)

George S. Houston

George S. Houston (1811-1879) was a lawyer, state and federal representative, and governor who was the archetype “Bourbon” Democrat in the turbulent years after the Civil War and Reconstruction. Chosen as the man to lead Alabama out of Reconstruction, Houston beneficially laid the groundwork for relieving the state from its crushing debt, but he also expanded the barbaric convict-lease system. The verdict of history aside, in his own time Houston was considered a hero by most of Alabama’s white voters.

George S. Houston

George S. Houston (1811-1879) was a lawyer, state and federal representative, and governor who was the archetype “Bourbon” Democrat in the turbulent years after the Civil War and Reconstruction. Chosen as the man to lead Alabama out of Reconstruction, Houston beneficially laid the groundwork for relieving the state from its crushing debt, but he also expanded the barbaric convict-lease system. The verdict of history aside, in his own time Houston was considered a hero by most of Alabama’s white voters.

George Smith Houston was born on January 17, 1811, to David Ross Houston, the son of Irish immigrants, and Hannah Pugh Reagan, in Williamson County, Tennessee, near the town of Franklin. When Houston was 16, the family moved to Alabama’s Tennessee Valley and settled near Florence, in Lauderdale County. Houston worked on the family farm and attended school at a local academy. Early on, he developed a fondness for books, read law in the office of Judge George Coalter of Florence, and completed his studies in a private law school at Harrodsburg, Kentucky.

Houston returned to Florence and soon parlayed his legal credentials into a political career. In 1831, he was elected from Lauderdale County to the state House of Representatives as a Jacksonian Democrat. Houston was appointed a district solicitor in 1834 but was defeated when he sought popular election to that office the next winter. He then moved east to Limestone County and opened a law office in the county seat of Athens. In May 1835, he married Mary I. Beatty, and they had a large family of eight children, four of whom died before 1860. His wife died around that time as well, and in 1861 Houston married Ellen Irvine of Florence, with whom he had two additional children. Houston was a successful cotton farmer and a shrewd investor, and by 1860 he possessed large landholdings and 78 enslaved people.

Tenure in the State House

Successful in his 1837 effort to recapture the solicitor’s position, Houston held the office until 1841, when he was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives as a Democrat. Houston began an influential career as a member of the House, where he remained until 1861, except for one two-year term. During his long tenure, Houston served on the committee on territories and chaired three powerful committees: military, ways and means, and judiciary. He lost popularity temporarily when he led the opposition in north Alabama to South Carolina senator John C. Calhoun’s 1849 “Address of the Southern Delegates in Congress to Their Constituents,” which questioned the federal government’s right to limit slavery in territories gained in the war with Mexico. As a Unionist, Houston was one of only four southern Democrats who refused to sign the document, and he asserted that those who supported it were exacerbating mounting sectional tensions. Because of his stand on this issue, opposition to him grew. He wisely sat out one term, ran again in the 1851 election, and won.

Houston’s political longevity can be attributed to several factors. He was an impressive figure who was known for his temperate habits and thoughtful demeanor. Further, the Union Democrat shared ideas with the Whigs, which helped explain his long political strength in the Tennessee Valley.

Civil War

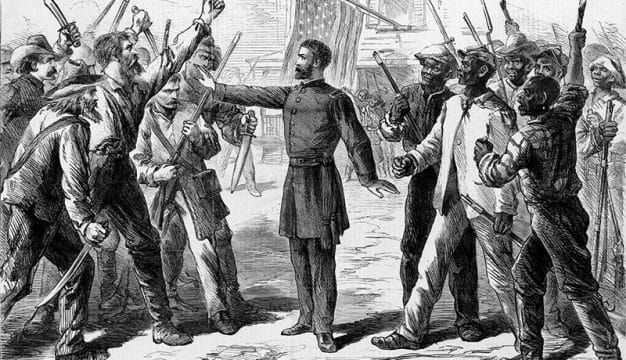

John Basil Turchin

Houston campaigned for Democrat Stephen A. Douglas for president in 1860 and opposed secession, refusing to sign a statement by southern congressmen denouncing the Republicans and advocating secession. He was a member of the House of Representatives’ “Committee of Thirty-Three,” which proposed a constitutional amendment in December 1860 forbidding Congress ever to abolish slavery. Yet in 1861, after his state seceded from the Union, he joined the Alabama delegation who resigned their offices and returned home.

John Basil Turchin

Houston campaigned for Democrat Stephen A. Douglas for president in 1860 and opposed secession, refusing to sign a statement by southern congressmen denouncing the Republicans and advocating secession. He was a member of the House of Representatives’ “Committee of Thirty-Three,” which proposed a constitutional amendment in December 1860 forbidding Congress ever to abolish slavery. Yet in 1861, after his state seceded from the Union, he joined the Alabama delegation who resigned their offices and returned home.

Houston retired to Athens and took no part in the Civil War. Two of his sons served in the Confederate Army, and Houston, sympathetic to his state and region, refused to take an oath of allegiance to federal authority. In 1862, his property was overrun by U.S. Army colonel John Basil Turchin‘s troops as they sacked and plundered Athens.

When Andrew Johnson attempted to implement Presidential Reconstruction, Houston was elected to the U.S. Senate. Shortly afterward, Johnson’s radical Republican opponents gained control of Congress and refused to seat Houston and other southerners. In 1866, Houston served as a delegate to the National Union Convention in Philadelphia, an abortive attempt by President Johnson to create a new political party to oppose the Radical Republicans. In 1867, Houston was defeated in a bid for a U.S. Senate seat by former governor John A. Winston and returned to his law practice. He played no role in Alabama’s Reconstruction struggles between 1867 and 1874.

Elected Governor

The gubernatorial election of 1874 was significant for both the state’s Democrats and its Republicans. It determined future control of Alabama and, with it, the state’s political and economic future. Democrats felt a sense of urgency about regaining the state from the racially integrated Republican Party. They persuaded white Alabamians to put aside historic differences and unite to “redeem” the state. To lead this alliance, they chose Houston, who was acceptable to both Unionists and south Alabamians. Democrats reinforced their single-minded appeal to white supremacy by promising honesty and economy as opposed to Republican profligacy. To ensure success, some Democrats resorted to intimidation and violence against Republicans, especially blacks. In a record turnout, Houston defeated incumbent David Lewis with 107,118 to 93,934 votes, a victory attributable to the increase in white voters, particularly among north Alabama Unionists.

Houston’s two administrations set the agenda for the “Bourbon” Democrats, a name that referred to the return of the royal house in France following the French Revolution and the Napoleonic wars. Republicans used the term pejoratively to mean reactionary and unenlightened. To Democrats, it meant a return to conservatism, limited government, and white supremacy.

In an unexpected bright spot for this conservative era, the not-yet-fully Bourbon legislature finally approved creation of a state public health board in 1875, after years of debate. Alabama was one of the first states in the nation to establish such a board, but no monies were appropriated for its work until 1879, when legislators approved $3,000 annually. Alabama’s Board of Health wisely gave complete control of public health issues to the state’s medical association and the physicians who were its members, thus freeing it to a large degree from political influence.

Shrinking Alabama Population

Although yellow fever and other diseases regularly caused loss of life, Alabama’s declining population resulted more from a migration of blacks and whites from the troubled state during the war and Reconstruction. With the increased need for industrial labor, Houston strongly promoted immigration but with limited success. In the interest of economy, if not humanity, he expanded the state’s practice of leasing its prisoners to private contractors, a cruel system and a dark stain on Alabama’s reputation.

Houston’s efforts to implement change in the state’s educational system also were thwarted. The foremost reason for his failure was the dire financial situation that he inherited, with railroad bonds being the most controversial part of the state’s debt problem, which some put at $30 million. With legislative authorization, Houston named himself head of a three-man commission to study the debt issue and recommend a program for retiring it.

Houston named Tristam B. Bethea, a Mobile financier, and Levi W. Lawler, a Talladega plantation owner, as the other commission members. Bethea was not a stockholder in any company affected by the debt question, but Lawler had been a director of a railroad. Houston also had previously been a director of the Louisville and Nashville Railroad, and his law partner a director of another, a circumstance that in later times would have made the commission’s composition unlawful because of conflict-of-interest restrictions. The alternatives for a solution were to recognize the state’s obligation for the entire debt, repudiate the debt as fraudulent (an action Houston opposed), or pay only a portion of the debt. After a year of study and review, the commission came up with a complicated settlement. They decided to set the legitimate debt at $18 million, which they later reduced to $12.5 million. Not surprisingly, bondholders of the Republican-controlled Alabama & Chattanooga Railroad were the most adversely affected. Some interpreted the commission’s action as draconian, but in the long run it proved beneficial to the state, and Houston deserves major credit for the settlement.

Constitutional Convention

Another major reform that Houston and the Democrats contemplated was replacing the state constitution, adopted during the Republican regime in 1868. Legislators set a vote for the summer of 1875 to decide whether to have a constitutional convention. In general, the Republicans opposed the convention, and the Democrats favored it. The campaign was less tense than the governor’s election of 1874, and voter turnout was smaller, but bitterness and disputation abounded. Alabama voters favored the convention by a vote of 77,763 to 59,928. Voters elected 99 delegates—80 Democrats, 12 Republicans (of whom four were black), and 7 independents. At the convention, rivalry between Black Belt plantation owners and rising industrial and railroad barons resulted in victories for each side. These two groups later would form an alliance, known as the Black Belt-Big Mule coalition, that would give them economic and political power lasting well beyond the first half of the twentieth century.

The new constitution declared that no state could secede and among other things prohibited state and county aid to internal improvements, banned educational and property qualifications for voting or holding office, and separated election dates for federal and state elections to prevent Washington from monitoring statewide contests. The document also abolished several offices, including that of lieutenant governor. State office holders were limited to two-year terms and many had their salaries reduced. State taxes were limited, and separate schools for blacks and whites were required. The new constitution did retain the requirements for a popularly elected judiciary and general incorporation provisions from the old constitution. To avoid reprisals from the federal government, no mention was made of disfranchising blacks, whose votes were largely controlled by Black Belt plantation owners anyway. The constitution was submitted to the voters and won approval by a margin of almost 60,000 votes. Only four Black Belt counties, where black males voted in huge numbers, rejected the document.

Houston was reelected in 1876, easily defeating his Republican opponent and setting a two-term precedent for his Bourbon successors. He was elected to the U.S. Senate two years later, and upon leaving the governor’s office, boasted of his and his party’s accomplishments. Houston served in the Senate from March 4, 1879, until his death in Athens later that year on December 31. He was buried in Athens City Cemetery.

Note: This entry was adapted with permission from Alabama Governors: A Political History of the State, edited by Samuel L. Webb and Margaret Armbrester (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001).

Further Reading

- Fleming, Walter Lynwood. Civil War and Reconstruction in Alabama. New York: Columbia University Press, 1905.

- Going Allen. Bourbon Democracy in Alabama, 1874-1890. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1951.

- Koart, Virgil Paul. “The Administration of George Smith Houston, Governor of Alabama, 1874–1878.” Master’s thesis, Auburn University, 1963.

- McMillan, Malcolm. Cook Constitutional Development in Alabama, 1798-1901: A Study in Politics, the Negro, and Sectionalism. 1955. Reprint, Spartanburg, S.C.: Reprint Co., 1978.

- Wiggins, Sarah W. The Scalawag in Alabama Politics, 1865-1881. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1974.