Guy Hunt (1987-93)

Guy Hunt (1933-2009) was Alabama’s governor from 1987 to 1993, and the first Republican elected governor of Alabama since the Reconstruction era. He was also the first to be removed from that office following his 1993 conviction on ethics charges. On March 31, 1998, the Alabama Board of Pardons and Paroles, in a controversial action, pardoned him on grounds that Hunt was innocent of the charges brought against him.

Guy Hunt

Harold Guy Hunt was born on June 17, 1933, in Holly Pond in rural Cullman County. His parents were William Otto and Frances Holcombe Hunt. At an early age, Hunt joined the Mt. Vernon Primitive Baptist Church, and church and home became critical influences on Hunt. Less than a year out of high school and at only 17 years of age, Guy Hunt married Helen Chambers on February 25, 1951, and the couple would have four children. Hunt continued his family’s farming tradition. During the Korean War, Hunt served in both the 101st Airborne and the First Infantry divisions of the U.S. Army and earned a certificate of achievement for outstanding performance of military duty and the distinguished service medal. After his military service, Hunt returned to his family farm at Holly Pond and in 1958 was formally ordained as a minister in the Primitive Baptist Church.

Guy Hunt

Harold Guy Hunt was born on June 17, 1933, in Holly Pond in rural Cullman County. His parents were William Otto and Frances Holcombe Hunt. At an early age, Hunt joined the Mt. Vernon Primitive Baptist Church, and church and home became critical influences on Hunt. Less than a year out of high school and at only 17 years of age, Guy Hunt married Helen Chambers on February 25, 1951, and the couple would have four children. Hunt continued his family’s farming tradition. During the Korean War, Hunt served in both the 101st Airborne and the First Infantry divisions of the U.S. Army and earned a certificate of achievement for outstanding performance of military duty and the distinguished service medal. After his military service, Hunt returned to his family farm at Holly Pond and in 1958 was formally ordained as a minister in the Primitive Baptist Church.

In the early twentieth century, Cullman County had an active Republican presence, but during the New Deal era it became solidly Democratic and remained so until the 1960s. Hunt maintained his party affiliation, however, and thus faced long odds in upholding the Republican cause. In 1962, he ran unsuccessfully for the state Senate. He ran again on the Republican ticket in 1964 for probate judge of Cullman County, and this time he benefited when Alabamians in massive numbers voted the straight Republican ticket for Barry Goldwater and other Republicans. He was reelected without benefit of Goldwater’s coattails in 1970.

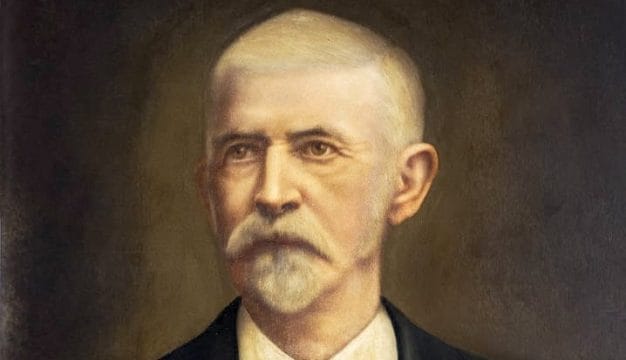

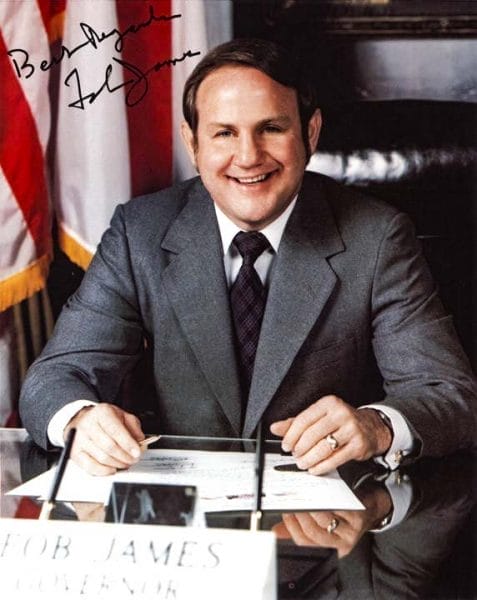

Forrest Hood James Jr.

In 1976, Hunt led Alabama’s delegation to the Republican National Convention in Kansas City and sought unsuccessfully to replace incumbent president Gerald Ford with Ronald Reagan as the party’s standard-bearer. Two years later, he made the first of his three runs for governor but was overwhelmingly defeated by Forrest “Fob” James, at the time a Democrat, in the general election. In 1980, Hunt served again as state chairman of the Alabama delegation to the Republican National Convention, which this time nominated Ronald Reagan for president. When Reagan was elected, Hunt was rewarded for his loyalty with an appointment as state executive director of the Agricultural Stabilization and Conservation Service.

Forrest Hood James Jr.

In 1976, Hunt led Alabama’s delegation to the Republican National Convention in Kansas City and sought unsuccessfully to replace incumbent president Gerald Ford with Ronald Reagan as the party’s standard-bearer. Two years later, he made the first of his three runs for governor but was overwhelmingly defeated by Forrest “Fob” James, at the time a Democrat, in the general election. In 1980, Hunt served again as state chairman of the Alabama delegation to the Republican National Convention, which this time nominated Ronald Reagan for president. When Reagan was elected, Hunt was rewarded for his loyalty with an appointment as state executive director of the Agricultural Stabilization and Conservation Service.

In 1985, Hunt resigned his position to focus on another run for the governorship, easily winning his party’s nomination in the June 1986 primary. Only about 33,000 Alabamians voted in this primary, however. The Democratic contest was more hard fought and more significant. Everyone, probably including Hunt, thought the next governor would be one of the better-known, long-time political figures squaring off in that primary. In the resulting runoff election on June 24, Attorney General Charlie Graddick narrowly defeated Lt. Gov. Bill Baxley. Graddick, the state’s chief law enforcement officer, was accused subsequently in a suit in federal court of having encouraged and allowed Republicans to vote in the Democratic primary, thereby diluting the votes of black voters and violating the provisions of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. Thus the state Democratic Party was ordered to either designate Baxley as its nominee or hold a new primary. Party leaders gave the nomination to Baxley, creating a furor among Alabama voters, who believed they had been stripped of their power to elect their governor of choice.

When Graddick abandoned a write-in candidacy, Hunt, originally viewed as the Republican’s sacrificial lamb, saw his chances against the Democratic nominee improve. Baxley ridiculed Hunt as unqualified because he had not attended college and worked as an Amway products distributor and chicken farmer in addition to being a part-time Primitive Baptist preacher. A rumor floated that Hunt was asked to leave his federal job because he had solicited campaign contributions from his employees. Hunt stressed economic development issues and courted conservative Democrats. He benefited from what the public perceived as “dirty Democratic” politics and was elected by a decisive 56 percent to 44 percent margin on November 4, 1986. He was the first Republican to hold this office since David P. Lewis in 1872.

Hunt was inaugurated on January 19, 1987, and despite his lack of state-level experience, he enjoyed some early successes. Within six months, the legislature passed a tort-reform package supported by the governor. The set of laws was passed in response to claims that Alabama juries were too liberal in their verdicts for plaintiffs in their civil disputes against companies, and the reform package sought to restrict such verdicts. The legislation was largely gutted, however, by Alabama Supreme Court decisions that upheld large settlements and declared that the enacted laws restricted the rights of citizens to unfettered trial by jury.

Hunt established a tax reform commission to review ways to restructure the state’s revenue system and increase funding for education, but the legislature refused to adopt its recommendations. He also created several commissions to study educational reform and from their work made numerous proposals for improving education, again with few results. During the last full year of his first term, education leaders in 14 poor Alabama counties filed a lawsuit against Hunt and other state officials charging that education appropriations were both inadequate and inequitable. Montgomery County circuit judge Gene Reese agreed and ordered the state to move toward providing equitable education funding to all counties.

Guy and Helen Hunt

Alabamians were pleased and not a little surprised when Hunt, in his first year in office, was identified by U.S. News and World Report as one of America’s best governors. Hunt took a personal interest in industrial recruitment and relished the governor’s role as leader of his political party, enthusiastically welcoming converts from the Democratic Party to the Republican fold. When Hunt ran for reelection in 1990, his Democratic opponent was Alabama Education Association leader Paul Hubbert, a formidable force in Alabama politics for two decades. Hunt again stressed industrial development, and Hubbert presented himself as Alabama’s opportunity to elect a “New South” governor. Tapping into the racial politics of the state, Republicans were successful in casting Hubbert as sympathetic to the liberal “national Democratic” agenda, which they labeled as pro-gay and pro–big government. In a controversial decision, they circulated photographs of Hubbert with various black politicians. Hunt defeated Hubbert by a 52 percent to 48 percent margin.

Guy and Helen Hunt

Alabamians were pleased and not a little surprised when Hunt, in his first year in office, was identified by U.S. News and World Report as one of America’s best governors. Hunt took a personal interest in industrial recruitment and relished the governor’s role as leader of his political party, enthusiastically welcoming converts from the Democratic Party to the Republican fold. When Hunt ran for reelection in 1990, his Democratic opponent was Alabama Education Association leader Paul Hubbert, a formidable force in Alabama politics for two decades. Hunt again stressed industrial development, and Hubbert presented himself as Alabama’s opportunity to elect a “New South” governor. Tapping into the racial politics of the state, Republicans were successful in casting Hubbert as sympathetic to the liberal “national Democratic” agenda, which they labeled as pro-gay and pro–big government. In a controversial decision, they circulated photographs of Hubbert with various black politicians. Hunt defeated Hubbert by a 52 percent to 48 percent margin.

In his second inaugural speech, Hunt again emphasized education reform. He proposed testing new teachers for their competence, providing and mandating kindergarten, lengthening the school year, strengthening graduation requirements, and increasing school-choice options for students and parents to force accountability and improvements in schools that were unfit. Many of Hunt’s proposals were included in the Alabama Education Improvement Act, which passed the legislature in July 1991. The law was mostly symbolic, however, because no funds to implement its policies were provided. The effects of a national recession caused revenue shortfalls for Alabama, and Hunt was forced to prorate state budgets in early 1991.

Controversy began to surround Hunt that summer after his use of state planes to fly to religious events in neighboring states was made public. Because Hunt accepted “love offerings” for preaching while on these trips, his use of planes for nonpublic purposes was attacked. In response to the criticism, he agreed to stop using the planes and reimbursed the state for earlier trips. The Alabama Ethics Commission, however, did not let the matter drop and in September 1991 recommended that Democratic attorney general Jimmy Evans prosecute Hunt. The governor and state Republicans believed that the attack on him was partisan, and they may have had a point because Alabama politics had not generally demanded the highest ethical standards for its officeholders.

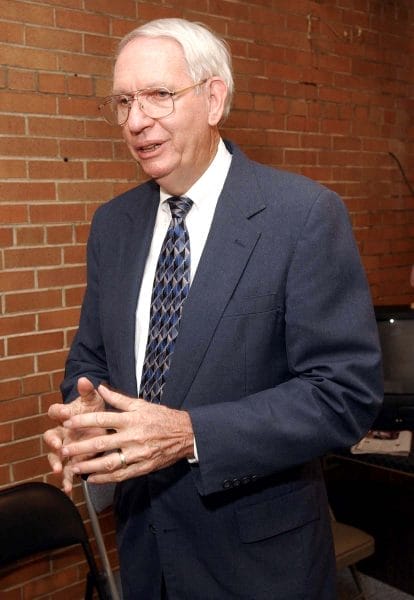

James E. Folsom Jr.

On December 28, 1992, Hunt was indicted on 13 felony counts, most of which were ultimately dropped. One charge that stuck stated that he had taken $200,000 from a 1987 inaugural fund, which included no tax or state funds, for his own personal use. Hunt vigorously denied that he had done anything illegal and again claimed a Democratic plot to force him from office. It was reported in the state’s press early in 1993 that attorneys for Hunt had sought an agreement that would allow him to plead guilty to a misdemeanor prior to the December felony indictments, but Evans would not consent. Prior to the trial, circuit judge Randall Thomas had urged Evans and Hunt’s lawyers to settle the criminal case against the governor, but they were unable to do so. On April 12, 1993, Hunt stood trial. The governor argued that any money he had taken was repayment for loans he had made to his unsuccessful 1978 campaign. The trial proceeded through six days of largely technical testimony, and most political observers believed that a jury would be disinclined to convict the governor. On April 22, 1993, however, after deliberating a total of only two hours, the jury rendered a verdict of guilty. Alabama law required Hunt’s immediate removal from office, and within hours James E. Folsom Jr., the Democratic lieutenant governor and eldest son of former governor “Big Jim” Folsom, was sworn in as Alabama’s new chief executive. Hunt’s sentencing came on May 7, and Judge Thomas ignored Evans’s arguments that Hunt should be jailed, limiting Hunt’s formal punishment to a $211,000 fine, 1,000 hours of community service, and five years’ probation.

James E. Folsom Jr.

On December 28, 1992, Hunt was indicted on 13 felony counts, most of which were ultimately dropped. One charge that stuck stated that he had taken $200,000 from a 1987 inaugural fund, which included no tax or state funds, for his own personal use. Hunt vigorously denied that he had done anything illegal and again claimed a Democratic plot to force him from office. It was reported in the state’s press early in 1993 that attorneys for Hunt had sought an agreement that would allow him to plead guilty to a misdemeanor prior to the December felony indictments, but Evans would not consent. Prior to the trial, circuit judge Randall Thomas had urged Evans and Hunt’s lawyers to settle the criminal case against the governor, but they were unable to do so. On April 12, 1993, Hunt stood trial. The governor argued that any money he had taken was repayment for loans he had made to his unsuccessful 1978 campaign. The trial proceeded through six days of largely technical testimony, and most political observers believed that a jury would be disinclined to convict the governor. On April 22, 1993, however, after deliberating a total of only two hours, the jury rendered a verdict of guilty. Alabama law required Hunt’s immediate removal from office, and within hours James E. Folsom Jr., the Democratic lieutenant governor and eldest son of former governor “Big Jim” Folsom, was sworn in as Alabama’s new chief executive. Hunt’s sentencing came on May 7, and Judge Thomas ignored Evans’s arguments that Hunt should be jailed, limiting Hunt’s formal punishment to a $211,000 fine, 1,000 hours of community service, and five years’ probation.

Guy Hunt

In June 1997, Hunt won his first victory in the matter when the Alabama Board of Pardons and Paroles approved a pardon for him on grounds of innocence. For the pardon to be valid, however, it needed to be signed by a judge or district attorney, but no one willing could be found. Even the recently elected Republican attorney general, Bill Pryor, refused to sign the pardon, arguing that he did not believe his office held that right or power. Then in a stunning defeat, when Hunt requested that probation be terminated shortly before it was due to expire in 1998, circuit judge Sally Greenhaw extended it for five more years because Hunt had been able to pay only $4,200 of the fine and court costs assessed against him. On March 30, 1998, however, Hunt’s probation was lifted when his attorney presented a check to the court for the entire balance. Sympathetic Alabamians, both Democrats and Republicans, had helped Hunt raise the needed funds. The next day, the Board of Pardons and Paroles again pardoned Hunt on grounds of innocence, and because probation had been terminated, no affirming signature was needed. The following day, Hunt qualified to run for the Republican nomination for governor against incumbent governor Fob James and three other contenders. Hunt failed to make the runoff and supported Winton M. Blount III against Fob James, who won the 1998 Republican runoff. Hunt returned to his Holly Pond farm and preaching engagements. He died from complications of lung cancer on January 30, 2009, in Birmingham.

Guy Hunt

In June 1997, Hunt won his first victory in the matter when the Alabama Board of Pardons and Paroles approved a pardon for him on grounds of innocence. For the pardon to be valid, however, it needed to be signed by a judge or district attorney, but no one willing could be found. Even the recently elected Republican attorney general, Bill Pryor, refused to sign the pardon, arguing that he did not believe his office held that right or power. Then in a stunning defeat, when Hunt requested that probation be terminated shortly before it was due to expire in 1998, circuit judge Sally Greenhaw extended it for five more years because Hunt had been able to pay only $4,200 of the fine and court costs assessed against him. On March 30, 1998, however, Hunt’s probation was lifted when his attorney presented a check to the court for the entire balance. Sympathetic Alabamians, both Democrats and Republicans, had helped Hunt raise the needed funds. The next day, the Board of Pardons and Paroles again pardoned Hunt on grounds of innocence, and because probation had been terminated, no affirming signature was needed. The following day, Hunt qualified to run for the Republican nomination for governor against incumbent governor Fob James and three other contenders. Hunt failed to make the runoff and supported Winton M. Blount III against Fob James, who won the 1998 Republican runoff. Hunt returned to his Holly Pond farm and preaching engagements. He died from complications of lung cancer on January 30, 2009, in Birmingham.

Hunt became governor of Alabama as a result of a squabble within the Democratic Party that offended Alabama voters, and few people expected him to achieve great success in that office. He surprised many people with his serious approach to governing and his efficient administration of the state’s agencies. His successes, however, will always be marred by his conviction and removal from office.

Note: This entry was adapted with permission from Alabama Governors: A Political History of the State, edited by Samuel L. Webb and Margaret Armbrester (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001).

Further Reading

- Mullaney, Marie M. Biographical Directory of the Governors of the United States, 1988–1994. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1994.