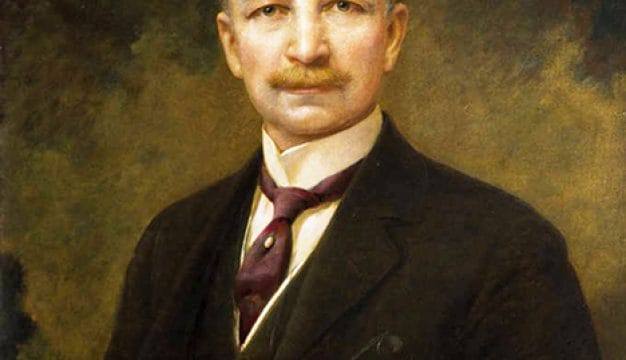

John Tyler Morgan

John Tyler Morgan

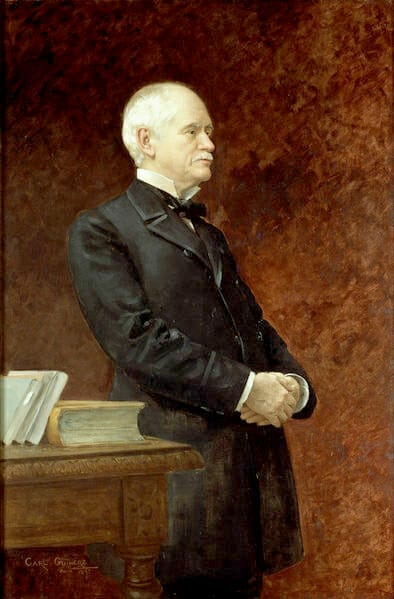

Remembered for his six terms and 30 years of service as a U.S. senator, John Tyler Morgan (1824-1907) was notable in two arenas of American politics, foreign policy and race relations. As one of the primary architects of the nation’s foreign policy during the era of global imperialist expansion, Morgan argued tirelessly for construction of the Panama Canal and for increasing America’s territorial holdings. As one of the most outspoken white supremacists of the early Jim Crow era, he vigorously championed the racist policies of Black disfranchisement and racial segregation. Morgan advocated the removal of the Black population of the South to foreign shores and thus combined his support of imperialism and racism into a “southern nationalist” philosophy that called for an aggressive, militaristic, and paternalistic approach toward the non-white peoples of the world.

John Tyler Morgan

Remembered for his six terms and 30 years of service as a U.S. senator, John Tyler Morgan (1824-1907) was notable in two arenas of American politics, foreign policy and race relations. As one of the primary architects of the nation’s foreign policy during the era of global imperialist expansion, Morgan argued tirelessly for construction of the Panama Canal and for increasing America’s territorial holdings. As one of the most outspoken white supremacists of the early Jim Crow era, he vigorously championed the racist policies of Black disfranchisement and racial segregation. Morgan advocated the removal of the Black population of the South to foreign shores and thus combined his support of imperialism and racism into a “southern nationalist” philosophy that called for an aggressive, militaristic, and paternalistic approach toward the non-white peoples of the world.

John Tyler Morgan

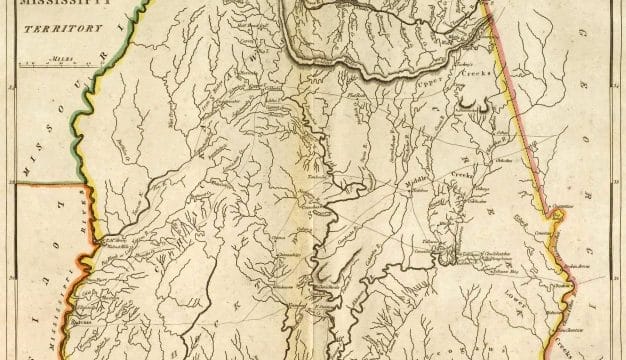

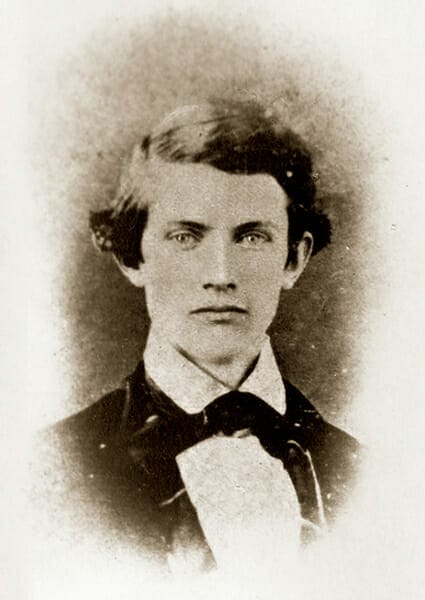

John Tyler Morgan was born on June 20, 1824, near the present-day town of Athens, in eastern Tennessee, to George Washington and Mary Frances Irby Morgan. In 1833, the family moved to what is now Calhoun County, Alabama. At the age of 20, without having attended college, Morgan passed the bar, having studied at a private law school in Tuskegee operated by his brother in law, Alabama Chief Justice William Parish Chilton. Morgan then established a law practice in Talladega. In 1846, he married Cornelia Willis, of the prominent Hardie family, with whom he had one son. In 1855, the family moved to Selma, the town Morgan would call home for the rest of his life. He participated in local and state politics, shifting among the Democratic, Whig, and Know-Nothing Parties. He first gained political prominence with his appointment as an aide to William Lowndes Yancey, one of the most radical supporters of secession during the years leading up to the Civil War. Like Yancey, Morgan took a leading role in the Alabama secession convention of 1861, arguing forcefully in favor of his state leaving the Union.

John Tyler Morgan

John Tyler Morgan was born on June 20, 1824, near the present-day town of Athens, in eastern Tennessee, to George Washington and Mary Frances Irby Morgan. In 1833, the family moved to what is now Calhoun County, Alabama. At the age of 20, without having attended college, Morgan passed the bar, having studied at a private law school in Tuskegee operated by his brother in law, Alabama Chief Justice William Parish Chilton. Morgan then established a law practice in Talladega. In 1846, he married Cornelia Willis, of the prominent Hardie family, with whom he had one son. In 1855, the family moved to Selma, the town Morgan would call home for the rest of his life. He participated in local and state politics, shifting among the Democratic, Whig, and Know-Nothing Parties. He first gained political prominence with his appointment as an aide to William Lowndes Yancey, one of the most radical supporters of secession during the years leading up to the Civil War. Like Yancey, Morgan took a leading role in the Alabama secession convention of 1861, arguing forcefully in favor of his state leaving the Union.

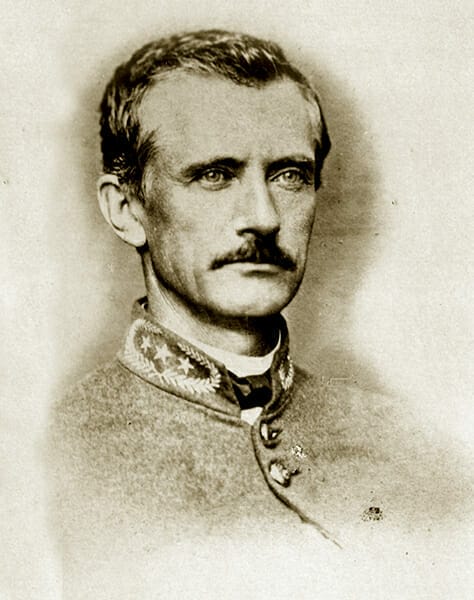

After war broke out, Morgan enlisted in the Confederate Army as a private and quickly rose to the rank of lieutenant-colonel, spending the first few months of the war fighting in Virginia. He then returned to Alabama and organized the 51st Alabama cavalry regiment, which served in the Army of Tennessee. He next received temporary reassignment as head of Alabama’s conscription office. In 1863, he earned a promotion to the rank of brigadier general, fighting under the command of generals Joseph E. Johnston and John Bell Hood in the futile defense of eastern Tennessee and northern Georgia in the crucial campaigns of 1864. Because there were two John Morgans serving as Confederate generals (the other being the more notable military figure and Huntsville native John Hunt Morgan), John Tyler Morgan was, by necessity, from then on known by his full name. Morgan had always taken pride in his middle name because it marked his kinship to former Pres. John Tyler of Virginia.

John Tyler Morgan

The defeat of the Confederacy left Morgan extremely bitter toward the federal government, the Republican Party, the North in general, and the formerly enslaved. Like so many other southerners during and after Reconstruction, he was never able to forgive those he perceived as enemies of his region’s way of life. Indeed, he epitomized what might be described as the “unreconstructed” ex-Confederate. Consequently, in the mid-1870s, Morgan led white Democrats in the effort to regain control of the state from Republican rule. By 1875, Alabama’s Democrats had succeeded in their effort through the adoption of a new Constitution. As a reward for his participation, the new Democratic legislature of Alabama rewarded Morgan with an appointment as a U.S. senator in 1876. Fully aware of racial and political goals of Alabama Democrats, the state’s senior senator serving in Washington, George E. Spencer, a carpetbagger from New York who served on the Committee of Privileges and Elections, tried to block Morgan’s confirmation. The mood in Washington was one of reconciliation, so the Senate confirmed Morgan, and he took his seat in 1877.

John Tyler Morgan

The defeat of the Confederacy left Morgan extremely bitter toward the federal government, the Republican Party, the North in general, and the formerly enslaved. Like so many other southerners during and after Reconstruction, he was never able to forgive those he perceived as enemies of his region’s way of life. Indeed, he epitomized what might be described as the “unreconstructed” ex-Confederate. Consequently, in the mid-1870s, Morgan led white Democrats in the effort to regain control of the state from Republican rule. By 1875, Alabama’s Democrats had succeeded in their effort through the adoption of a new Constitution. As a reward for his participation, the new Democratic legislature of Alabama rewarded Morgan with an appointment as a U.S. senator in 1876. Fully aware of racial and political goals of Alabama Democrats, the state’s senior senator serving in Washington, George E. Spencer, a carpetbagger from New York who served on the Committee of Privileges and Elections, tried to block Morgan’s confirmation. The mood in Washington was one of reconciliation, so the Senate confirmed Morgan, and he took his seat in 1877.

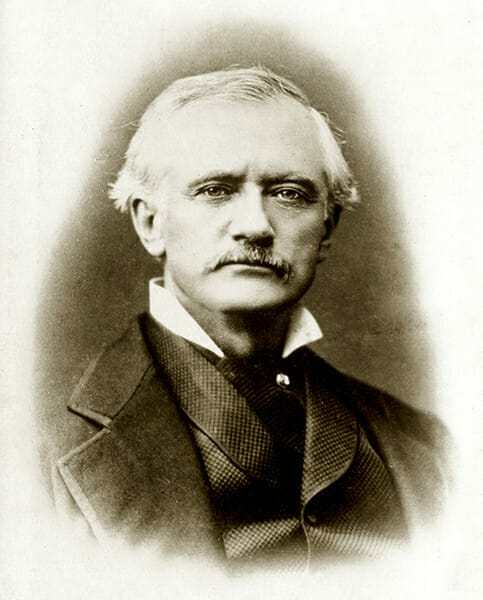

George E. Spencer

Once seated, Morgan settled into a Senate career in which he served at various times on four different committees: Rules, which he chaired for one term, Foreign Relations, Interoceanic Canals, and Public Health. Although best known for his efforts to promote white supremacy and foreign policy, Morgan rarely encountered a political issue on which he did not develop an opinion. He quickly earned a reputation as one of the most widely knowledgeable men of his generation. Some contemporaries even went so far as to call him a genius. His most distinguishing characteristic as a senator, however, was his status as one of the most loquacious debaters in the history of Congress. He once quipped that with adequate preparation he could talk for three days for or against a bill, but if unprepared he could talk indefinitely. Unlike most of his congressional colleagues, he firmly believed that his speeches delivered on the floor of the Senate actually could make a difference, if not in persuading fellow senators how to vote, then at least in shaping public opinion. This certainly proved true with regard to racial issues, as Morgan used the Senate floor for a bully pulpit to buttress and extend Jim Crow laws.

George E. Spencer

Once seated, Morgan settled into a Senate career in which he served at various times on four different committees: Rules, which he chaired for one term, Foreign Relations, Interoceanic Canals, and Public Health. Although best known for his efforts to promote white supremacy and foreign policy, Morgan rarely encountered a political issue on which he did not develop an opinion. He quickly earned a reputation as one of the most widely knowledgeable men of his generation. Some contemporaries even went so far as to call him a genius. His most distinguishing characteristic as a senator, however, was his status as one of the most loquacious debaters in the history of Congress. He once quipped that with adequate preparation he could talk for three days for or against a bill, but if unprepared he could talk indefinitely. Unlike most of his congressional colleagues, he firmly believed that his speeches delivered on the floor of the Senate actually could make a difference, if not in persuading fellow senators how to vote, then at least in shaping public opinion. This certainly proved true with regard to racial issues, as Morgan used the Senate floor for a bully pulpit to buttress and extend Jim Crow laws.

One of Morgan’s most effective speeches came in the notorious filibuster of the Federal Elections Bill of 1890—a bill designed primarily to enforce the voting rights of Black southerners by stationing federal troops at the polls. Although Morgan did not persuade any senator to change his vote, he undoubtedly helped to convince a majority of the American public of the inadvisability of such a plan, a main goal of his effort. He did not confine his disdain for the plan to the filibuster and wrote articles against it in leading political journals of the day, including Forum and Arena. His writings exhibit great skill in articulating what other racists were thinking but were unable to say and in explaining more clearly what other white supremacists had already said or written. Most notably, Morgan took ideas from Roger B. Taney, Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, whose infamous Scott v. Sandford ruling in 1857 had reduced Blacks to the status of livestock, and presented them in new form with great effectiveness for those trying to prove the inferiority of Blacks to whites.

As a member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in 1884, Morgan first began crusading for the voluntary emigration or forced deportation of Blacks from the American South. Over the next two decades, he explored various geographical possibilities for their relocation, including the Congo and the Philippines. Although he was neither the first, the last, nor most famous of the supporters of such a colonization plan, he may well have been the most persistent. Despite his impassioned pleas for support, most Senate colleagues dismissed the idea as impractical at best and impossible at worst. Yet his efforts were not totally inconsequential in charting the direction of American history, because they bolstered his work on the Foreign Relations Committee to get the U.S. government to pursue a vigorous global imperialist policy.

John Tyler Morgan

As one of the most ardent of the late-nineteenth century promoters of American expansionism, Morgan argued for the acquisition of Hawaii, Cuba, and the Philippines, all of which the United States took as either spoils of the Spanish-American War of 1898 or as byproducts of it. He also led the charge for the United States to build a canal somewhere across Central America, without regard to French efforts already taking place in Panama. After France abandoned its quest to build the canal, Morgan lobbied for the proposed Nicaragua route rather than continuing French efforts in Panama. He fought unsuccessfully for the alternate plan right up to the day that Pres. Theodore Roosevelt ordered digging to commence in Panama. Although his Nicaraguan canal was not to be, his decade-long drive to get the United States government to build a canal in Central America earned him the well-deserved title of the ideological father of the Panama Canal.

John Tyler Morgan

As one of the most ardent of the late-nineteenth century promoters of American expansionism, Morgan argued for the acquisition of Hawaii, Cuba, and the Philippines, all of which the United States took as either spoils of the Spanish-American War of 1898 or as byproducts of it. He also led the charge for the United States to build a canal somewhere across Central America, without regard to French efforts already taking place in Panama. After France abandoned its quest to build the canal, Morgan lobbied for the proposed Nicaragua route rather than continuing French efforts in Panama. He fought unsuccessfully for the alternate plan right up to the day that Pres. Theodore Roosevelt ordered digging to commence in Panama. Although his Nicaraguan canal was not to be, his decade-long drive to get the United States government to build a canal in Central America earned him the well-deserved title of the ideological father of the Panama Canal.

Although Morgan never ceased to consider himself an Alabamian and a southerner, he spent most of his public life in Washington, D.C., and thus progressed over the years from the champion of local and regional concerns to one of national concerns. He remained popular with constituents nonetheless and rarely faced a serious challenge for his Senate seat. He died in June 1907 and was buried in Selma.

Further Reading

- Baylen, Joseph O., and John Hammond Moore. “Senator John Tyler Morgan and Negro Colonization in the Philippines, 1901-1902.” Phylon 29 (Spring 1968): 65-75.

- Clayton, Lawrence A. “Canal Morgan.” Alabama Heritage 25 (Summer 1992): 6-19.

- Fry, Joseph A. John Tyler Morgan and the Search for Southern Autonomy. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1992.

- Upchurch, Thomas Adams. “Senator John Tyler Morgan and the Genesis of Jim Crow Ideology, 1889-1891.” Alabama Review 57 (April 2004): 110-31.