Cotton

Cotton Boll

Cotton, perhaps more than anything else, was the driving economic force in the creation of Alabama. The search for land to grow cotton attracted the first settlers into the state’s river valleys. Cotton also created the two dominant labor systems, slavery in the Old South and sharecropping in the New South. The cotton-based economy also produced cycles of boom and bust resulting from the Civil War, the boll weevil infestation, government crop controls (such as acreage allotments and yield quotas), competition from foreign growers, and other factors. In the early days of cotton production, it was used primarily for fabric, but today cotton has a wide range of uses. Cotton lint is still used for textiles, and the fuzz left on the cotton seed after ginning (referred to as linter) is used in a variety of products: explosives, upholstery, writing paper, U.S. currency, and film and videotape. The oil extracted from cottonseed is used in cooking, cosmetics, soap, and many other items. The seed husk and the material that remains after oil extraction is used for fertilizer and livestock feed. Although cotton is no longer “king” in Alabama agriculture, it is still an important part of the state’s economy. Of the 17 states that produce cotton, Alabama ranks about seventh.

Cotton Boll

Cotton, perhaps more than anything else, was the driving economic force in the creation of Alabama. The search for land to grow cotton attracted the first settlers into the state’s river valleys. Cotton also created the two dominant labor systems, slavery in the Old South and sharecropping in the New South. The cotton-based economy also produced cycles of boom and bust resulting from the Civil War, the boll weevil infestation, government crop controls (such as acreage allotments and yield quotas), competition from foreign growers, and other factors. In the early days of cotton production, it was used primarily for fabric, but today cotton has a wide range of uses. Cotton lint is still used for textiles, and the fuzz left on the cotton seed after ginning (referred to as linter) is used in a variety of products: explosives, upholstery, writing paper, U.S. currency, and film and videotape. The oil extracted from cottonseed is used in cooking, cosmetics, soap, and many other items. The seed husk and the material that remains after oil extraction is used for fertilizer and livestock feed. Although cotton is no longer “king” in Alabama agriculture, it is still an important part of the state’s economy. Of the 17 states that produce cotton, Alabama ranks about seventh.

Butler County Cotton Field 1937

Indigenous to warm climates throughout the world, cotton was well known to ancient agricultural societies. The Greek historian Herodotus mentioned “tree-wool” grown in India, and other ancient writers recorded its cultivation in Egypt, Asia Minor, China, Greece, Africa, Italy and several Mediterranean islands. In Mexico, the Aztecs grew cotton, which they spun and wove into very fine cloth, long before Christopher Columbus reported cotton growing in the West Indies. Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto noted in his journal the use of a “delicate white cloth” by Indians of the South. It is uncertain when European settlers first cultivated cotton in Alabama, but one early historian believed it was in production by 1772. One of the first cotton planters in Alabama was Joseph Collins, a surveyor for the Spanish government at Mobile. In 1795, Collins imported 10 enslaved Africans from Kentucky and established a cotton plantation near Mobile. Collins may have set the pattern for future development of the Alabama plantation system, but the great northern river valleys of Alabama soon overshadowed Mobile’s agricultural successes. Collins’s importation of African slaves also demonstrated the importance of slave labor for the cultivation of cotton, and wherever cotton went slavery followed.

Butler County Cotton Field 1937

Indigenous to warm climates throughout the world, cotton was well known to ancient agricultural societies. The Greek historian Herodotus mentioned “tree-wool” grown in India, and other ancient writers recorded its cultivation in Egypt, Asia Minor, China, Greece, Africa, Italy and several Mediterranean islands. In Mexico, the Aztecs grew cotton, which they spun and wove into very fine cloth, long before Christopher Columbus reported cotton growing in the West Indies. Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto noted in his journal the use of a “delicate white cloth” by Indians of the South. It is uncertain when European settlers first cultivated cotton in Alabama, but one early historian believed it was in production by 1772. One of the first cotton planters in Alabama was Joseph Collins, a surveyor for the Spanish government at Mobile. In 1795, Collins imported 10 enslaved Africans from Kentucky and established a cotton plantation near Mobile. Collins may have set the pattern for future development of the Alabama plantation system, but the great northern river valleys of Alabama soon overshadowed Mobile’s agricultural successes. Collins’s importation of African slaves also demonstrated the importance of slave labor for the cultivation of cotton, and wherever cotton went slavery followed.

The Cotton Plant

Most of the cotton grown around the world before 1793, when Eli Whitney’s simple yet effective cotton gin became widely available, was long-staple cotton (Gossypium barbadense), which grows best along tropical or subtropical coastlines. Its individual fibers, called staples, are long and fluffy, and it has fewer seeds than other varieties of cotton. Another member of the genus is Gossypium hirsutum, known as upland or short-staple cotton. Like long-staple cotton, upland cotton grows as a shrub or small tree with a single trunk and has smooth, gray bark that is tough and stringy.

Upland cotton is the preferred species for Alabama. It requires a rather long growing season of 180 to 200 days from seed to full maturity. In Alabama, it is often planted in March or April, after the danger of frost has passed. It thrives during the summer when temperatures reach 90 degrees or above during the day and remain at about 70 degrees at night. Upland cotton grows on almost any type of soil, but it prefers rich sandy loam that drains well. Upland cotton plants have large, dark green leaves, and in summer, the appearance of white, cream, or pale yellow flowers signals to farmers that it is time for them to cease cultivation until harvest. When the blooms fall, small square pods, called bolls, begin to emerge and grow until they reach the size of a plum. The bolls ripen in the hot sun until late August (if the crop was planted in April), then burst open into chambered areas of fluffy white cotton. Cotton bolls usually have three to five staples or sections that produce white or brown fibers containing embedded seeds. The seeds generally range in color and texture from black and smooth to green and fuzzy.

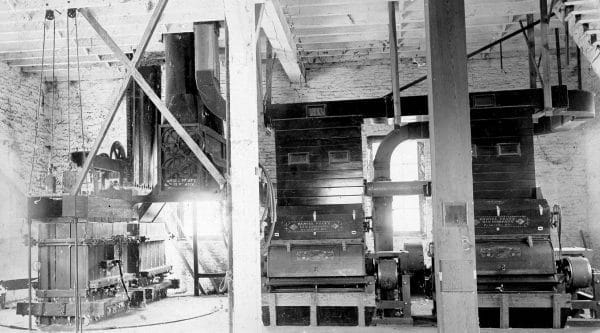

Pratt Gin Factory Machinery

These seeds were a major drawback to upland cotton because they are almost impossible to remove by hand from the staple. An average enslaved worker could extract seeds from only about 50 pounds a day. For this reason, cotton was generally shunned as a viable cash crop until the Whitney cotton gin became available in 1793. This remarkably simple invention stimulated cotton production by mechanically removing seeds, creating a lust for cotton land that quickly led to settlement and statehood for Alabama.

Pratt Gin Factory Machinery

These seeds were a major drawback to upland cotton because they are almost impossible to remove by hand from the staple. An average enslaved worker could extract seeds from only about 50 pounds a day. For this reason, cotton was generally shunned as a viable cash crop until the Whitney cotton gin became available in 1793. This remarkably simple invention stimulated cotton production by mechanically removing seeds, creating a lust for cotton land that quickly led to settlement and statehood for Alabama.

Early Cotton Production

Farmers began to push into present-day Alabama’s fertile river valleys when the state was still part of the Mississippi Territory. These rivers provided natural highways, via steamboats, into the interior of the territory and broad fertile plains for growing cotton. Prior to the Civil War, the two most important areas for cotton cultivation were the Tennessee River Valley and the Black Belt, a swath of rich black soil that ranges from the west-central counties into the upper-southeast counties. These two regions, and to a lesser extent the Coosa Valley and the Chattahoochee basin, helped turn Alabama from a region of virgin forest and canebrakes dotted with Indian towns and cornfields into one of the most productive agricultural regions in America. It is estimated that as much as 90 percent of the farmers engaged in the production of cotton and corn.

As of 1820, Alabama produced an estimated 25,390 bales of cotton (at about 225 pounds per bale), or 3.7 percent of the national total. (Today the average bale weighs about 500 pounds). In 1830 Alabama exported goods, including cotton, which were valued at $2.2 million through the port of Mobile, and north Alabama, mainly the Tennessee Valley, exported cotton through New Orleans valued at almost $2 million. Within two decades the economics of cotton production had changed dramatically. By 1849, Alabama led the nation in cotton production, and with 22.9 percent of the national total 10 years later, the “Cotton Kingdom” was firmly established in the state. Great fortunes were made and Alabama soon became one of the 10 wealthiest states in the nation. That wealth was made possible, however, only by the work of enslaved people.

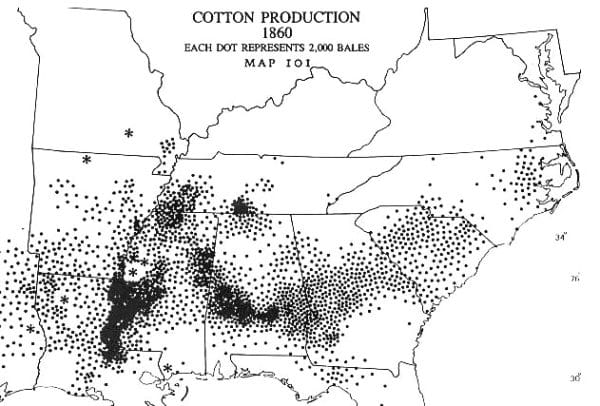

Cotton Production 1860

Cotton is a very labor-intensive crop and requires abundant labor, thus African slaves were indispensable to plantation agriculture. As the white population of Alabama grew, so did the enslaved population and in certain areas of the state at a higher rate. Between 1810 and 1820, Alabama’s white population grew by about 1,000 percent, reaching 127,901 by 1820. The enslaved population grew by about the same rate in southwest Alabama, the Black Belt region, and the Tennessee Valley. Between 1810 and 1860, the enslaved population of the Tennessee River Valley grew from about 20 percent of the total population to almost 53 percent. The slave presence in the Black Belt was even higher. Slaves made up only 30 percent of the total population in 1819, but 40 years later the ratio in many areas had risen to well over 50 percent of the region’s total population.

Cotton Production 1860

Cotton is a very labor-intensive crop and requires abundant labor, thus African slaves were indispensable to plantation agriculture. As the white population of Alabama grew, so did the enslaved population and in certain areas of the state at a higher rate. Between 1810 and 1820, Alabama’s white population grew by about 1,000 percent, reaching 127,901 by 1820. The enslaved population grew by about the same rate in southwest Alabama, the Black Belt region, and the Tennessee Valley. Between 1810 and 1860, the enslaved population of the Tennessee River Valley grew from about 20 percent of the total population to almost 53 percent. The slave presence in the Black Belt was even higher. Slaves made up only 30 percent of the total population in 1819, but 40 years later the ratio in many areas had risen to well over 50 percent of the region’s total population.

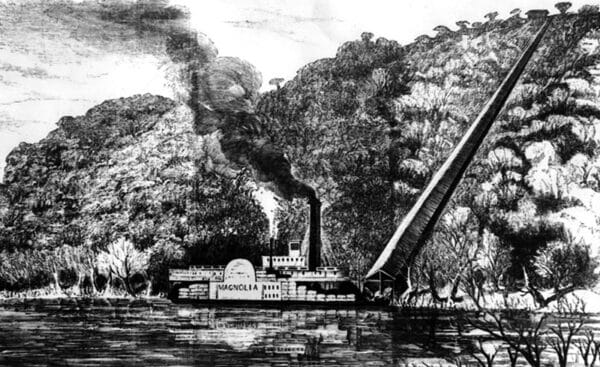

Cotton Slide

Just before the Civil War, cotton made up about 60 percent of all U.S. exports, prompting southerners to believe that “King Cotton” would shield them from political domination by the northern states and serve as a viable economic force in the creation of the Confederate States of America. Neither belief proved true. As the Civil War unfolded in 1861, southern ports were blockaded and cotton piled up on the docks, but production continued. The price of cotton in 1861 was $0.13 a pound; and three years later prices had risen to $1.01 a pound, making it hard for the state government to convince Alabama farmers to plow under their cotton fields to plant corn and other food crops. As early as September 1861, Gov. Andrew B. Moore urged farmers to switch from cotton to food crops, and the state legislature even placed a $0.10 per pound tax on all seed cotton over 2,500 pounds per laborer in order to limit production. Thus, if cotton was bringing $0.13 per pound on the market, the tax reduced the value of all cotton over 2,500 pounds per worker to a mere $0.03. But Alabama farmers were slow to respond and continued to produce more cotton than they could sell.

Cotton Slide

Just before the Civil War, cotton made up about 60 percent of all U.S. exports, prompting southerners to believe that “King Cotton” would shield them from political domination by the northern states and serve as a viable economic force in the creation of the Confederate States of America. Neither belief proved true. As the Civil War unfolded in 1861, southern ports were blockaded and cotton piled up on the docks, but production continued. The price of cotton in 1861 was $0.13 a pound; and three years later prices had risen to $1.01 a pound, making it hard for the state government to convince Alabama farmers to plow under their cotton fields to plant corn and other food crops. As early as September 1861, Gov. Andrew B. Moore urged farmers to switch from cotton to food crops, and the state legislature even placed a $0.10 per pound tax on all seed cotton over 2,500 pounds per laborer in order to limit production. Thus, if cotton was bringing $0.13 per pound on the market, the tax reduced the value of all cotton over 2,500 pounds per worker to a mere $0.03. But Alabama farmers were slow to respond and continued to produce more cotton than they could sell.

In 1861, the Confederate government had passed an act requiring Confederate forces to destroy all cotton that might fall into the hands of U.S. Army troops. By 1865, this act was rigorously enforced. The Federal Captured and Abandoned Property Act of 1863 required federal forces to transport confiscated cotton back behind Union lines when possible. When it could not be moved, the cotton was to be destroyed. Despite the confiscation and destruction of cotton and the reduction of acreage, Alabama had more cotton on hand than any other southern state at the end of the war at a time when virtually all foreign and domestic markets for American cotton had dried up. During the war, England and France had shifted to Egyptian cotton but had returned to the cheaper American cotton as of 1866.

Rise of Sharecropping and Tenant Farming

The Civil War devastated Alabama’s economy. Wartime destruction of property and losses due to the emancipation of slaves reached into millions of dollars. Emancipation also meant that Alabama farmers had to produce cotton with a new system of labor. The most viable cash crop was still cotton, and the most viable labor source was the emancipated slave population.

Cotton Harvesting, ca. 1930s

Various labor solutions were proposed in Alabama, including importing German immigrants from northern states and workers from China. Neither of these proved to be practical, and some other form of labor had to be found. At the prompting of the Freedman’s Bureau, the system that eventually evolved was based on sharecropping and tenancy. Although these two terms are sometimes viewed as synonymous, they are not. Tenant farmers typically rent land for cash, whereas sharecroppers are laborers who keep a portion of the crop they produce. Sharecropping, which came to be the most dominant labor system throughout Alabama, was designed for freedpeople who had nothing to bring into a rental agreement except their ability to work. Whites from the hill county also came down into the river valleys to sharecrop, but they generally were restricted to marginal land until the latter part of the nineteenth century. This system was in full operation by the 1870s, and although it shared many of the harsh aspects of slavery, it gave freed people a certain degree of independence. By 1920, some 78 percent of Alabamians still lived on farms, and 58 percent of those farms were operated by tenant farmers. In 1930, the ratio of tenant farmers rose to 65 percent, whereas there were 37,600 white and 27,500 black sharecroppers.

Cotton Harvesting, ca. 1930s

Various labor solutions were proposed in Alabama, including importing German immigrants from northern states and workers from China. Neither of these proved to be practical, and some other form of labor had to be found. At the prompting of the Freedman’s Bureau, the system that eventually evolved was based on sharecropping and tenancy. Although these two terms are sometimes viewed as synonymous, they are not. Tenant farmers typically rent land for cash, whereas sharecroppers are laborers who keep a portion of the crop they produce. Sharecropping, which came to be the most dominant labor system throughout Alabama, was designed for freedpeople who had nothing to bring into a rental agreement except their ability to work. Whites from the hill county also came down into the river valleys to sharecrop, but they generally were restricted to marginal land until the latter part of the nineteenth century. This system was in full operation by the 1870s, and although it shared many of the harsh aspects of slavery, it gave freed people a certain degree of independence. By 1920, some 78 percent of Alabamians still lived on farms, and 58 percent of those farms were operated by tenant farmers. In 1930, the ratio of tenant farmers rose to 65 percent, whereas there were 37,600 white and 27,500 black sharecroppers.

Decline of the Cotton Kingdom

By 1866, cotton had again blanketed Alabama’s fields, with 977,000 acres harvested, yielding about 120 pounds per acre for a total of 264,000 bales. In 1867, Alabamians planted almost 1.25 million acres of cotton averaging 152 pounds per acre. As of 1877, Alabama had more than 2 million acres of cotton in cultivation and harvested 673,000 bales that year. Cotton was making a comeback, but the increase in production was tied to the increase in acres planted. Yield per acre remained low, however, averaging 149.8 pounds per acre from 1866 through 1876. The next two decades saw per-acre yields drop even lower. Some of the reasons for the drop in productivity were limited access to fertilizer, soil erosion, adverse weather conditions, and a loss of farming skills among younger generations of black farmers. Ironically, during this period of decline, the Alabama exhibit on cotton research won a silver medal at the 1900 World’s Fair in Paris, France.

Boll Weevil

Alabama cotton farmers suffered another huge setback in 1910, when the boll weevil, a small Central American insect that feeds on cotton, first reached the state. Within a few years, the insects had devastated Alabama’s cotton fields, and by 1916, cotton production dropped from 155 pounds to 95 pounds per acre. Many farmers, especially in south Alabama, turned to growing peanuts until the boll weevil blight passed.

Boll Weevil

Alabama cotton farmers suffered another huge setback in 1910, when the boll weevil, a small Central American insect that feeds on cotton, first reached the state. Within a few years, the insects had devastated Alabama’s cotton fields, and by 1916, cotton production dropped from 155 pounds to 95 pounds per acre. Many farmers, especially in south Alabama, turned to growing peanuts until the boll weevil blight passed.

During World War I and the years shortly afterward, the cotton market improved. To keep cotton out of enemy hands, England purchased a large portion of American cotton, producing artificially inflated prices and a boom for American cotton farmers. England, a major cotton importer, sought out other markets, and foreign countries began competing with the United States, producing 40 percent of the world’s cotton, leaving the United States with about a 60 percent share of the market, down from 69.2 percent in 1900. In 1919, southern cotton farmers produced a crop valued at $2 billion, the most lucrative harvest to date. In the 1920s, acreage devoted to cotton averaged around 3 million acres annually, whereas cotton production averaged between 150 and 200 pounds to the acre. In contrast, the total world production increased by 9 million bales between 1915 and 1939, whereas production in the American South increased by only 407,000 bales. At the same time, cotton prices began to spiral downward.

In the spring of 1920, cotton was selling for about $0.42 a pound in New Orleans, and by October the price had dropped to $0.20. In December, prices slid to $0.13 a pound. Some farmers in Alabama and other southern states organized a grower’s association in an effort to halt the decline by withholding crops from the market until prices increased, but to no avail. Prices continued to fall, and some farmers in south Alabama returned to growing peanuts.

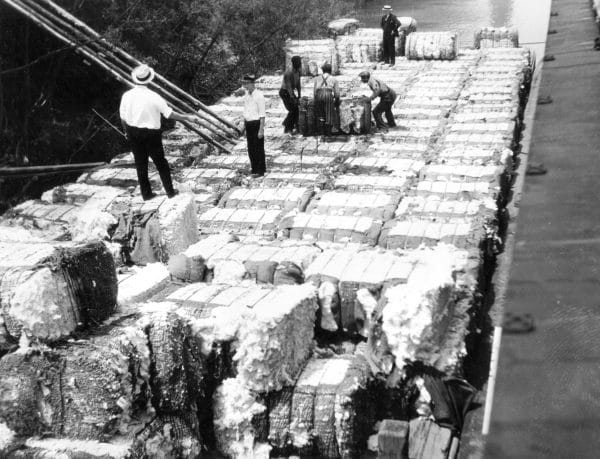

Cotton Barge on the Warrior River

Several federal programs attempted to aid southern cotton farmers in the 1920s, but little was accomplished until Pres. Franklin D. Roosevelt instituted his New Deal programs in response to the Great Depression. The president signed into law the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1933, a bill supported by Alabama senator John Hollis Bankhead II, which paid cotton farmers to plow under one-third of their crops to reduce production and raise cotton prices. The act helped landowners but hurt many sharecroppers, who made up most of the farming population, because their labor was no longer needed. Later, Bankhead and his brother William, a congressman, co-sponsored the Cotton Control Act of 1934, which limited the number of bales a farmer could produce. In 1936, the U.S. Supreme Court declared the Agriculture Adjustment Act of 1933 unconstitutional in United States v. Butler. Congress and the president responded by enacting the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1938, partly drafted by Bankhead, which mandated price supports for cotton and other crops. This act also created the cotton allotment program, which required farmers to plant a specified number of acres of cotton and established a quota system to balance supply and demand.

Cotton Barge on the Warrior River

Several federal programs attempted to aid southern cotton farmers in the 1920s, but little was accomplished until Pres. Franklin D. Roosevelt instituted his New Deal programs in response to the Great Depression. The president signed into law the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1933, a bill supported by Alabama senator John Hollis Bankhead II, which paid cotton farmers to plow under one-third of their crops to reduce production and raise cotton prices. The act helped landowners but hurt many sharecroppers, who made up most of the farming population, because their labor was no longer needed. Later, Bankhead and his brother William, a congressman, co-sponsored the Cotton Control Act of 1934, which limited the number of bales a farmer could produce. In 1936, the U.S. Supreme Court declared the Agriculture Adjustment Act of 1933 unconstitutional in United States v. Butler. Congress and the president responded by enacting the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1938, partly drafted by Bankhead, which mandated price supports for cotton and other crops. This act also created the cotton allotment program, which required farmers to plant a specified number of acres of cotton and established a quota system to balance supply and demand.

As a result of the cotton allotment system, farmers applied more fertilizer, producing more cotton on less land, which in turn reduced the price of cotton. The government continued its attempt to reduce cotton acreage by several methods, most notably the Soil Bank program of 1956, which paid farmers to take land out of production. This program was viewed as a failure, but by 1960 some 30 million acres of various kinds of croplands lay fallow.

Labor Shortages and Mechanization

Baldwin County Cotton Farm

Cotton farmers in the South and in Alabama also had to deal with labor problems throughout much of the twentieth century. A massive exodus of African Americans from the South and out of farming, part of the Great Migration, created a shortage of farm workers. There was also a loss of farm labor to war industries and the armed forces during World War I and World War II. Only about 80,000 Alabamians served in the military during World War I, but that number jumped to 321,00 during World War II. The solution to labor shortages was mechanization for those who could afford it, and family-based farming such as sharecropping for those who could not.

Baldwin County Cotton Farm

Cotton farmers in the South and in Alabama also had to deal with labor problems throughout much of the twentieth century. A massive exodus of African Americans from the South and out of farming, part of the Great Migration, created a shortage of farm workers. There was also a loss of farm labor to war industries and the armed forces during World War I and World War II. Only about 80,000 Alabamians served in the military during World War I, but that number jumped to 321,00 during World War II. The solution to labor shortages was mechanization for those who could afford it, and family-based farming such as sharecropping for those who could not.

Agricultural machinery was expensive, but by 1930 there were more than 4,600 tractors on Alabama farms. As of 1940, that number had almost doubled, and within a decade, almost 46,000 tractors were plowing Alabama fields. Another innovation was the mechanical cotton picker, perfected by International Harvester in the early 1940s. A mechanical harvester could pick almost 1,000 pounds of cotton per hour compared with the 15 to 20 pounds per hour a human could pick. But mechanical cotton pickers were expensive, and few farmers could afford them.

Cotton production declined throughout much of the twentieth century as a result of federal legislation, natural causes, and crop diversification. In the 1930s alone, cotton acreage dropped by 1.4 million acres. Between 1952 and 1980, cotton acreage dropped by 1.2 million acres. At the same time, yield per acre was increasing, signifying the adoption of more scientific methods of farming. Cotton almost disappeared from south Alabama in the 1970s and 1980s, due primarily to crop diversification. A new peanut allotment program was adopted in 1977 and revised in 1996 as an incentive to grow peanuts, and cotton production dropped below half a million acres annually. Cotton remained the dominant cash crop for the state, and the Black Belt and the Tennessee Valley continued to be Alabama’s centers of cotton production.

Cotton’s Future

Cotton did make a slow comeback in the 1990s, with cultivation again reaching an average of more than a half million acres annually. Productivity was also up, except in a few years of adverse weather conditions. During the 1990s, yields averaged above 600 pounds an acre, but fewer farmers were cultivating cotton. In 1992, only 1,469 Alabamians whose principle occupation was farming were planting cotton. In 2001, yield was 730 pounds per acre. In the drought years of 2002 and 2006, however, yields per acre fell dramatically to 507 pounds and 583 pounds per acre, respectively.

Old Rotation Experiment Field

At the start of the twenty-first century, it is difficult to determine the future of cotton production in Alabama. Factors such as changing weather patterns, the high cost of machinery, changing agricultural policies, world trade issues, rising input costs, and alternative choices in fabrics will all affect the future of cotton production in Alabama. There is the distinct possibility that the crop that gave rise to Alabama and that has both cost and benefited the state so much in so many ways might become only a minor crop. After decades of acreage reduction, cotton appeared to be making a comeback as one of the mainstays of Alabama agriculture. In 2017, farmers planted 435,000 acres of cotton and harvested 343,000 acres, with 931 pounds per acre. But since the year 2000, cotton acreage has gone from about half of the planted acres of the big four row crops in Alabama (corn, cotton, peanuts, soybeans) to about a quarter of the acreage. For the time being, however, cotton remains a very important part of the state’s agricultural economy.

Old Rotation Experiment Field

At the start of the twenty-first century, it is difficult to determine the future of cotton production in Alabama. Factors such as changing weather patterns, the high cost of machinery, changing agricultural policies, world trade issues, rising input costs, and alternative choices in fabrics will all affect the future of cotton production in Alabama. There is the distinct possibility that the crop that gave rise to Alabama and that has both cost and benefited the state so much in so many ways might become only a minor crop. After decades of acreage reduction, cotton appeared to be making a comeback as one of the mainstays of Alabama agriculture. In 2017, farmers planted 435,000 acres of cotton and harvested 343,000 acres, with 931 pounds per acre. But since the year 2000, cotton acreage has gone from about half of the planted acres of the big four row crops in Alabama (corn, cotton, peanuts, soybeans) to about a quarter of the acreage. For the time being, however, cotton remains a very important part of the state’s agricultural economy.

Further Reading

- Davis, Charles S. Cotton Kingdom in Alabama. 1939. Reprint, Philadelphia: Porcupine Press, 1974.

- Fite, Gilbert C. Cotton Fields No More: Southern Agriculture, 1865-1980. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1984.

- Phillips, Kenneth Edward. “Jubilee in the Fields: Alabama’s Landless Farmers in a Cotton-Dominated Society.” Ph.D. diss., Auburn University, 1999.