Populism in Alabama

During the last three decades of the nineteenth century, farmers in Alabama and across the United States faced a variety of economic problems, ranging from rising and unregulated railroad freight rates to falling crop prices. Frustrated farmers formed organizations to address such problems and, because these organizations were technically nonpartisan, they also formed third parties to represent their interests. These efforts coalesced in the 1890s with the founding of the People’s (or Populist) Party, which in Alabama drew considerable support not only from small, landowning farmers, sharecroppers, and tenant farmers but also from organized labor, especially coal miners.

Precedents to Populism

The large-scale organization of Alabama farmers into a cohesive movement began in 1872, when the Patrons of Husbandry (better known as the Grange) reached the state. This national organization provided members with social and educational benefits and promoted

Winston County Farmer

cooperative purchasing and selling enterprises as a solution to farmers’ economic difficulties. By 1877, the Grange claimed 678 local chapters in Alabama and 14,440 members. Led chiefly by planters who were affiliated with the Democratic Party, the Grange proved too conservative for some of its rank and file. By 1878, some Alabama farmers, especially in the northern part of the state, began to revolt against the Democratic Party by supporting the Greenback-Labor Party (GLP) or independent candidates. Coal miners in the Birmingham district also gave considerable support to the GLP.

Winston County Farmer

cooperative purchasing and selling enterprises as a solution to farmers’ economic difficulties. By 1877, the Grange claimed 678 local chapters in Alabama and 14,440 members. Led chiefly by planters who were affiliated with the Democratic Party, the Grange proved too conservative for some of its rank and file. By 1878, some Alabama farmers, especially in the northern part of the state, began to revolt against the Democratic Party by supporting the Greenback-Labor Party (GLP) or independent candidates. Coal miners in the Birmingham district also gave considerable support to the GLP.

By the mid-1880s, the GLP had disintegrated and the Grange had lost much of its membership as its cooperative enterprises failed. But farmers’ organizations with more radical agendas, such as the biracial Agricultural Wheel, the Farmers’ Alliance, and the Colored Farmers’ Alliance, superseded the Grange, and during 1887 and 1888, representatives of various farmer and labor groups organized a third party in Alabama. Initially known as the Union Labor Party and subsequently as the Labor Party of Alabama, this party won some local elections in 1888 in the hill country counties of Chilton, Cullman, and Shelby, as well as in Baldwin County on the Gulf Coast. These isolated victories foretold greater third-party strength in the 1890s.

By the end of 1889, the Farmers’ Alliance had absorbed the Agricultural Wheel and claimed about 120,000 members in Alabama, and the Colored Alliance reported a membership of at least 50,000 by the end of 1890. In addition to reviving the practice of cooperative enterprises, the Farmers’ Alliance also supported the free coinage of silver, governmental regulation of railroads (or ownership if regulatory efforts proved unsuccessful), and a farm credit scheme called the

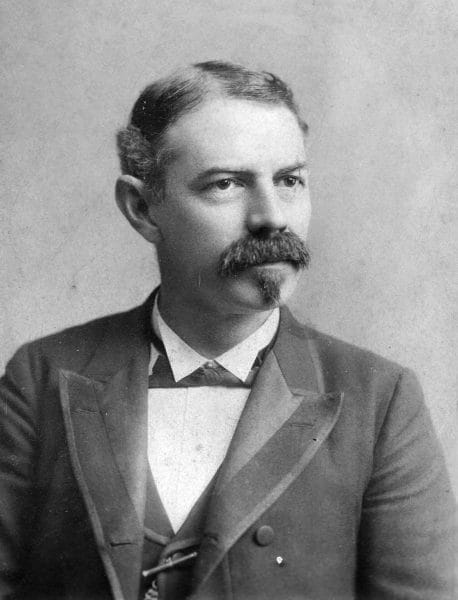

Thomas Goode Jones, ca. 1895

subtreasury plan. This plan, which never won congressional approval, called upon the federal government to build warehouses to store nonperishable crops and to loan paper currency to farmers against those crops at low interest rates. In addition, the Alabama Farmers’ Alliance supported the state’s commissioner of agriculture, Reuben F. Kolb, for the Democratic Party’s gubernatorial nomination in 1890. The Democrats nominated state militia commander Thomas Goode Jones however, and failed to support much of the Alliance program.

Thomas Goode Jones, ca. 1895

subtreasury plan. This plan, which never won congressional approval, called upon the federal government to build warehouses to store nonperishable crops and to loan paper currency to farmers against those crops at low interest rates. In addition, the Alabama Farmers’ Alliance supported the state’s commissioner of agriculture, Reuben F. Kolb, for the Democratic Party’s gubernatorial nomination in 1890. The Democrats nominated state militia commander Thomas Goode Jones however, and failed to support much of the Alliance program.

The Birth of the Populist Party

In May 1891, some 1,400 delegates from farmer organizations as well as the Knights of Labor attended a conference in Cincinnati at which they laid the groundwork for a new national party, the People’s Party, which soon became more commonly known as the Populist Party. In July, the Geneva County Farmers’ Alliance declared its support for the new party, and the Marshall and Calhoun county alliances did likewise by the year’s end. In March 1892, the Alabama Knights of Labor urged its members to support the Populists, and weeks later Alabama Farmers’ Alliance president Samuel M. Adams called for an “Alliance Labor” conference to be held in Birmingham on May 30 to consider action on the People’s Party platform. On June 23, 1892, the first state convention of the Alabama Populist Party met in Birmingham.

Populist Campaigns

Some white Alabama Alliancemen supported the Populist platform, which was derived from the demands of the Farmers’ Alliance, but they found it difficult to break with the Democratic Party, which was then widely considered in the South to be “the white man’s party.” They therefore formed the Jeffersonian Democratic Party, but this party was in fact indistinguishable from

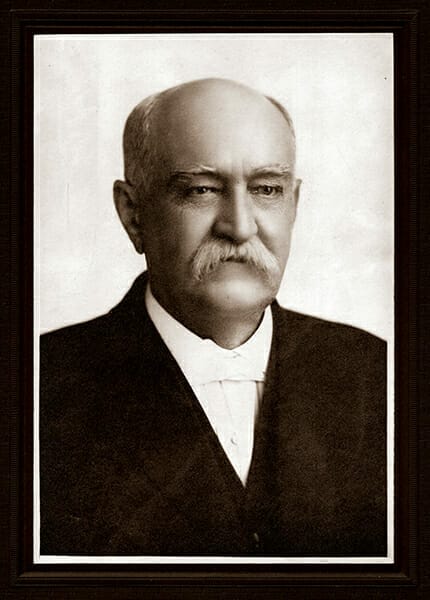

Reuben F. Kolb

the state’s Populist Party and supported the same candidates. Kolb was the best known of these candidates; he ran for governor in 1892 and 1894. Kolb pledged that as governor he would protect the legal and political rights of blacks, for which the state’s Democratic press condemned him. He also made a strong effort to win industrial workers’ votes by promising to abolish the state’s convict-lease system. His appeal to labor became particularly significant during his second campaign, during which some 9,000 of the state’s coal miners were on strike. Had the state’s elections been conducted honestly and fairly, Kolb most certainly would have won both times, but Democrats’ manipulation of vote counts in the Black Belt counties secured narrow victories for the Democratic candidates. As one historian has noted, “Fraud had not been seen on such a scale since Reconstruction.”

Reuben F. Kolb

the state’s Populist Party and supported the same candidates. Kolb was the best known of these candidates; he ran for governor in 1892 and 1894. Kolb pledged that as governor he would protect the legal and political rights of blacks, for which the state’s Democratic press condemned him. He also made a strong effort to win industrial workers’ votes by promising to abolish the state’s convict-lease system. His appeal to labor became particularly significant during his second campaign, during which some 9,000 of the state’s coal miners were on strike. Had the state’s elections been conducted honestly and fairly, Kolb most certainly would have won both times, but Democrats’ manipulation of vote counts in the Black Belt counties secured narrow victories for the Democratic candidates. As one historian has noted, “Fraud had not been seen on such a scale since Reconstruction.”

Despite Democrats’ use of such despicable tactics, the Populists managed to win two congressional elections in Alabama in 1894: Milford Wriarson Howard in the Seventh District in the north Alabama hill country and Albert Taylor Goodwyn in the Fifth District, which spanned the hill country and Black Belt.

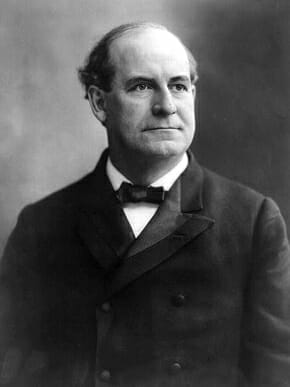

Bryan, William Jennings

Not surprisingly, however, the initial results in the latter election favored the Democratic candidate, and the Populist candidate took his seat in Congress only after filing and following through with an election contest before the U.S. House of Representatives. In 1896, the Alabama Populist Party pursued a complicated strategy that involved fusion (or ticket-sharing) with the Republican Party in state and congressional elections and the Democrats in the presidential election, as “free silver” candidate William Jennings Bryan represented the Democrats and Populists against gold-standard Republican William McKinley. Populist state and congressional candidates lost in Alabama, Bryan lost nationally, and the Populist Party soon fell apart. By 1900, the party no longer mattered in state or national politics.

Bryan, William Jennings

Not surprisingly, however, the initial results in the latter election favored the Democratic candidate, and the Populist candidate took his seat in Congress only after filing and following through with an election contest before the U.S. House of Representatives. In 1896, the Alabama Populist Party pursued a complicated strategy that involved fusion (or ticket-sharing) with the Republican Party in state and congressional elections and the Democrats in the presidential election, as “free silver” candidate William Jennings Bryan represented the Democrats and Populists against gold-standard Republican William McKinley. Populist state and congressional candidates lost in Alabama, Bryan lost nationally, and the Populist Party soon fell apart. By 1900, the party no longer mattered in state or national politics.

The Populist Legacy

Although the Populist movement failed, it did not mark the end of political protest by Alabama farmers and laborers. In northern Alabama, many former Populists found an outlet for their reformist agenda in the progressive wing of the Republican Party. In Birmingham, some former Populist (and Knights of Labor) leaders became Socialists, and their party achieved some local strength before the national Socialist movement was crushed during World War I. Throughout the state, the Farmers’ Union and the State Federation of Labor kept the Populist spirit alive by advocating reforms such as low-interest loans to tenant farmers and the abolition of the convict-lease system, a demand that the state government finally met in 1928. Thus, the Populist movement left a legacy of farmer-labor reform in Alabama that lived on even after the Populist Party itself had perished.

Additional Resources

Clark, John B. Populism in Alabama. Auburn, Ala.: Auburn Printing Co., 1927.

Hackney, Sheldon. Populism to Progressivism in Alabama. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1969.

Hild, Matthew. Greenbackers, Knights of Labor, and Populists: Farmer-Labor Insurgency in the Late-Nineteenth-Century South. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2007.

Rogers, William Warren. The One-Gallused Rebellion: Agrarianism in Alabama, 1865-1896. 1970. Reprint, Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001.

Webb, Samuel L. Two-Party Politics in the One-Party South: Alabama’s Hill Country, 1874-1920. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1997.