Rural Studio

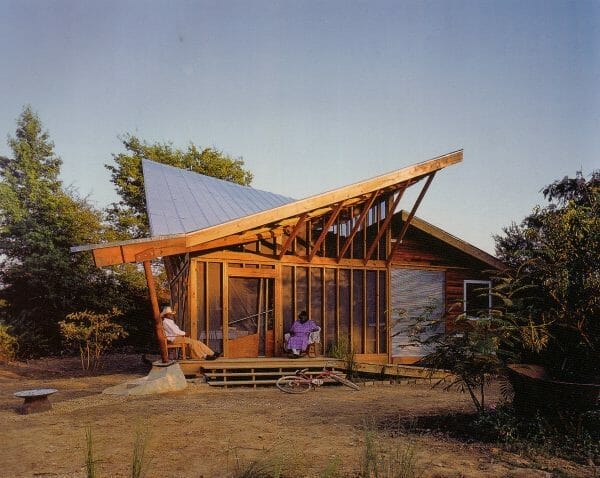

Butterfly House

The Rural Studio, a program of Auburn University’s College of Architecture, Design and Construction, has earned an admirable international reputation and has been widely imitated. Based in Hale County, one of Alabama‘s poorest counties, the studio has designed and built dozens of unique houses and community buildings for impoverished families. By moving predominately white architecture students out of university classrooms and into largely African American Black Belt communities, the studio not only has taught young architects to design and construct exceptional buildings, but also to forge relationships in a world that most of them would not have encountered otherwise. In addition to being a social welfare and education program, the studio, which employs donated, leftover, salvaged, and nontraditional materials, has also become a model for sustainability in construction.

Butterfly House

The Rural Studio, a program of Auburn University’s College of Architecture, Design and Construction, has earned an admirable international reputation and has been widely imitated. Based in Hale County, one of Alabama‘s poorest counties, the studio has designed and built dozens of unique houses and community buildings for impoverished families. By moving predominately white architecture students out of university classrooms and into largely African American Black Belt communities, the studio not only has taught young architects to design and construct exceptional buildings, but also to forge relationships in a world that most of them would not have encountered otherwise. In addition to being a social welfare and education program, the studio, which employs donated, leftover, salvaged, and nontraditional materials, has also become a model for sustainability in construction.

The Beginnings

Samuel Mockbee

The Rural Studio was established in 1993 by professors Dennis K. Ruth, then head of Auburn’s architecture department, and architecture professor Samuel Mockbee, an idealist who believed that everyone, rich or poor, deserved an inspiring home. He was convinced that architecture should have a moral aspect and that architects should care more about improving living conditions than their own fame and fortune. Mockbee took over as head of the studio, first in the Hale County seat of Greensboro and then nine miles down the road in tiny Newbern. He chose the location for the studio because Hale County’s poverty rate was more than 30 percent and the residents, mostly African American, had little chance of other outside help. The studio’s 150-mile distance from Auburn ensured that students would have few distractions from their work in the community.

Samuel Mockbee

The Rural Studio was established in 1993 by professors Dennis K. Ruth, then head of Auburn’s architecture department, and architecture professor Samuel Mockbee, an idealist who believed that everyone, rich or poor, deserved an inspiring home. He was convinced that architecture should have a moral aspect and that architects should care more about improving living conditions than their own fame and fortune. Mockbee took over as head of the studio, first in the Hale County seat of Greensboro and then nine miles down the road in tiny Newbern. He chose the location for the studio because Hale County’s poverty rate was more than 30 percent and the residents, mostly African American, had little chance of other outside help. The studio’s 150-mile distance from Auburn ensured that students would have few distractions from their work in the community.

Mason’s Bend

Hay Bale House

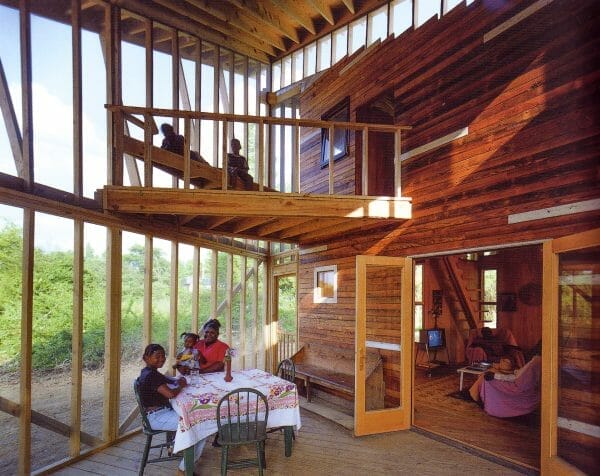

In 1994, with a $250,000 grant from the Alabama Power Foundation, the studio designed and constructed its first two houses and its first community building in Mason’s Bend. The community consists of four extended families of about 100 people who lived in tumbledown dwellings along a dirt road at a bend in the Black Warrior River. The studio’s first house was for Shepherd and Alberta Bryant, who had been living with their three grandchildren in an unheated shack without plumbing. The Bryants explained to Mockbee and his students that they wanted mainly two things in a house: a big front porch and a room big enough for a bed and a desk for each of the three children.

Hay Bale House

In 1994, with a $250,000 grant from the Alabama Power Foundation, the studio designed and constructed its first two houses and its first community building in Mason’s Bend. The community consists of four extended families of about 100 people who lived in tumbledown dwellings along a dirt road at a bend in the Black Warrior River. The studio’s first house was for Shepherd and Alberta Bryant, who had been living with their three grandchildren in an unheated shack without plumbing. The Bryants explained to Mockbee and his students that they wanted mainly two things in a house: a big front porch and a room big enough for a bed and a desk for each of the three children.

To create an inexpensive, well-insulated dwelling, the students constructed walls using hay bales wrapped in polyurethane that were fastened with wire, stacked like bricks, and then covered with stucco. In the finished dwelling, known appropriately as the Hay Bale House, three barrel-shaped niches for the children extend from the rear of the main interior space, and a wide covered porch runs the length of the house in front.

Butterfly House, Porch

The Rural Studio’s second house was for Anderson Harris and his disabled wife Ora Lee. Mockbee and his students observed that the couple enjoyed spending time on their small porch, so the studio created a house with a large porch that includes a wide ramp to accommodate Ora Lee’s wheelchair. The sharply angled wing-like porch roof accounts for the nickname “Butterfly House.” The two-story roof design allows for ample air circulation and also channels rainwater into a cistern. Costs were kept low by using reclaimed tin for the roof and heart pine recycled from an old church.

Butterfly House, Porch

The Rural Studio’s second house was for Anderson Harris and his disabled wife Ora Lee. Mockbee and his students observed that the couple enjoyed spending time on their small porch, so the studio created a house with a large porch that includes a wide ramp to accommodate Ora Lee’s wheelchair. The sharply angled wing-like porch roof accounts for the nickname “Butterfly House.” The two-story roof design allows for ample air circulation and also channels rainwater into a cistern. Costs were kept low by using reclaimed tin for the roof and heart pine recycled from an old church.

In addition to designing and building individual homes, the Rural Studio under Mockbee built a range of distinctive structures, including chapels, churches, community centers, playgrounds, and outdoor pavilions. All the work combined Mockbee’s modern aesthetic with his appreciation of southern vernacular forms, such as big overhanging roofs and wide porches.

How it Works

Students with Clients

Each semester, approximately 15 second-year students and a comparable number of fifth-year students live and work in and around Newbern, a town consisting of a general store and a post office. In the early days of the Rural Studio, students chose a client from a list provided by the Hale County Department of Human Resources. More recently, professors have chosen the clients.

Students with Clients

Each semester, approximately 15 second-year students and a comparable number of fifth-year students live and work in and around Newbern, a town consisting of a general store and a post office. In the early days of the Rural Studio, students chose a client from a list provided by the Hale County Department of Human Resources. More recently, professors have chosen the clients.

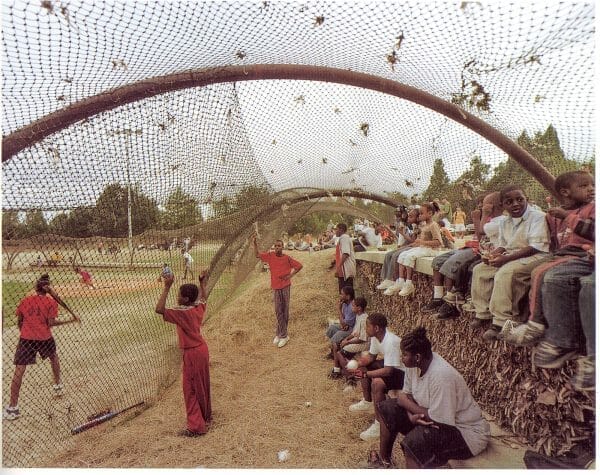

The second-year students, who stay one semester working on a house, meet with family members to identify their needs and then design a suitable dwelling and lay a foundation. The next semester, a new group of students continues the work, modifying the design as needed. It takes approximately a year to finish a house. The fifth-year students spend a full academic year in Hale County and work in small groups on community-oriented projects. In 1999, the studio established an outreach program for students from other universities and other disciplines who work on projects of their choosing. Some of their projects are architectural; some serve other community needs. The studio has collaborated with many local civic organizations, such as the Hale Empowerment and Rehabilitation Organization (HERO) in Greensboro, for which the studio renovated a storefront and designed and built a community center and playground.

A Change of Leadership

Newbern Little League Baseball Field

In 1998, Mockbee was diagnosed with leukemia, and in late December 2001 succumbed to the disease. Andrew Freear, an associate professor and Mockbee protégé hired in 2000, became co-director. Ruth left in 2002 to lead a different program back at Auburn University, and Bruce Lindsey, then head of Auburn’s architecture department, stepped in to become co-director. Lindsey subsequently left Auburn, and Freear assumed the sole leadership position.

Newbern Little League Baseball Field

In 1998, Mockbee was diagnosed with leukemia, and in late December 2001 succumbed to the disease. Andrew Freear, an associate professor and Mockbee protégé hired in 2000, became co-director. Ruth left in 2002 to lead a different program back at Auburn University, and Bruce Lindsey, then head of Auburn’s architecture department, stepped in to become co-director. Lindsey subsequently left Auburn, and Freear assumed the sole leadership position.

Shortly after Mockbee’s death, Auburn committed $400,000 a year to the studio for operating expenses, providing it with financial stability for the first time. The Rural Studio also added a board of directors consisting of Mockbee’s widow, donors, Auburn University administrators, and community leaders from the Black Belt region. The board initially provided oversight and direction, but its main purpose now is to raise the approximately $300,000 a year needed to help fund projects and pay other expenses.

The studio changed focus under Freear, who shifted efforts away from individual homes and more toward fifth-year projects and community-oriented buildings that have grown larger, more complex, more socially significant, and more numerous. During the studio’s early years, students typically had built one house and, at most, two modest community buildings a year.

Freear has tried, above all, to raise the level of craft, with an increased emphasis on planning and drawing, either by computer or by hand. He views drawings as a means for design teams to communicate better among themselves, better convey ideas to clients, and complete projects more quickly. Freear requires students to rehearse their client presentations in layman’s language so that clients are better informed.

The fire station in Newbern showcases some characteristics of the post-Mockbee Rural Studio. There is a shift of esthetic: sophistication has replaced quirkiness and off-the-shelf materials have replaced reclaimed materials. The structure, completed in 2004, is an elegant, twenty-first century version of a barn that reflects Freear’s aim to create buildings that require little or no maintenance. It is clad in pine and translucent polycarbonate, with south-facing horizontal cedar slats to provide shade in summer and admit low winter light. The interior is dominated by an exposed structure of steel and timber wall trusses stretched taut by heavy-gauge steel cables and metal anchors.

The studio also now tackles multi-year, phased projects. One example is the renovation of Perry Lakes Park, in Perry County, Hale’s neighbor to the west. An aluminum and cedar pavilion, completed in 2002, marked the beginning of the renovation. During the next academic year, students added three unusual restrooms: one is clad in stainless steel and cedar and focuses on a single tree; another rises 50 feet and is open to the sky, and the third is a raised square with a horizontal slit-opening. In 2005, students completed a 140-foot-long metal and cypress covered bridge that spans a bayou-like lake and makes the park’s more beautiful east side accessible by foot. As the projects have gotten larger and more complicated, the studio has tended to use fewer nontraditional materials but continues to emphasize sustainability and reuse.

Further Reading

- Dean, Andrea Oppenheimer, and Timothy Hursley. Rural Studio: Samuel Mockbee and an Architecture of Decency. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2002.