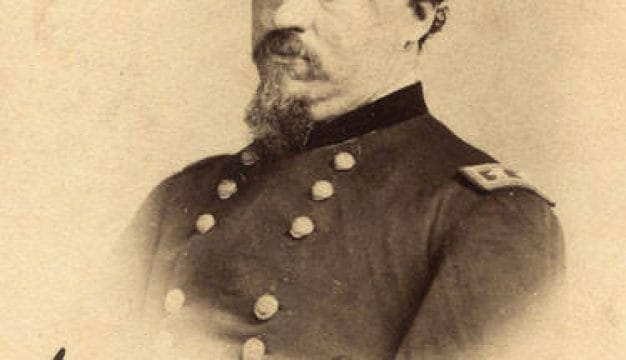

John Murphy (1825-29)

John Murphy

John Murphy (1785-1841) was an able political leader who took moderate stands on inflammatory states’ rights issues. His years as governor are associated with the relocation of the state capital to Tuscaloosa and the initiation of steps leading to the opening of the University of Alabama. He was among the drafters of the 1819 Constitution when Alabama became a state, served in the first session of the Alabama House of Representatives, was a state senator, and served Alabama in the U.S. Congress.

John Murphy

John Murphy (1785-1841) was an able political leader who took moderate stands on inflammatory states’ rights issues. His years as governor are associated with the relocation of the state capital to Tuscaloosa and the initiation of steps leading to the opening of the University of Alabama. He was among the drafters of the 1819 Constitution when Alabama became a state, served in the first session of the Alabama House of Representatives, was a state senator, and served Alabama in the U.S. Congress.

John Murphy was born in Robeson County, North Carolina, around 1785 to first-generation Scottish immigrant Neil Murphy and his wife. As a child, Murphy moved with his family to South Carolina, where he completed his preparatory education and taught school to earn money for college. He attended South Carolina College (now the University of South Carolina) in the same class with future Alabama governor John Gayle and another important antebellum political figure, James Dellet, both of whom later played important roles in Murphy’s political career in Alabama. Following his graduation in 1808, Murphy read law, which he never practiced, and for the next 10 years he served as clerk of the South Carolina Senate. He was also appointed a trustee of South Carolina College, a position he held from 1808 to 1818.

Murphy was married twice, first to Sarah Hails in South Carolina, the mother of his son John Murphy Jr. After her death, he married Sarah Darrington Carter, of Clarke County, Alabama, with whom he had several children, including son Duncan Murphy, who spent much of his life in California and served in its legislature. In 1818, Murphy moved to Monroe County in the southern portion of the newly created Alabama Territory. He bought land, developed a plantation, and quickly established himself as a man who commanded the respect of his peers. In 1819, he was elected as a delegate to the constitutional convention, where he served on the Committee of Fifteen that drafted the Constitution. He was elected as one of Monroe County’s five members of the House of Representatives in 1820, and in 1822, he was chosen the county’s only member of the Alabama Senate.

Israel Pickens

As an Alabama politician, Murphy quickly aligned himself with Israel Pickens‘s “popular” party. This group opposed the “Royal Party” or Georgia faction, which included governors William Wyatt Bibb and Thomas Bibb and U.S. senator John Williams Walker, and was viewed as the power behind the territorial legislation that permitted the charging of unrestricted interest rates and the privately owned and much disliked Planters and Merchants Bank of Huntsville. As a legislator, Murphy endorsed Pickens’s efforts to establish a state bank as a means of providing adequate capital for the currency-starved state, and he and Pickens forged a strong alliance.

Israel Pickens

As an Alabama politician, Murphy quickly aligned himself with Israel Pickens‘s “popular” party. This group opposed the “Royal Party” or Georgia faction, which included governors William Wyatt Bibb and Thomas Bibb and U.S. senator John Williams Walker, and was viewed as the power behind the territorial legislation that permitted the charging of unrestricted interest rates and the privately owned and much disliked Planters and Merchants Bank of Huntsville. As a legislator, Murphy endorsed Pickens’s efforts to establish a state bank as a means of providing adequate capital for the currency-starved state, and he and Pickens forged a strong alliance.

Old Cahawba Centennial Monument

The dominance of the Pickens forces was so great that Murphy was twice elected governor without opposition (in 1825 and 1827). The most important development in his first term was the decision to move the capital from Cahawba to Tuscaloosa. The 1819 Constitution provided for the first session of the legislature to be held in Huntsville and “all subsequent sessions at the town of Cahawba” until 1825, when legislators could “designate by law . . . the permanent seat of Government” without the need for concurrence by the governor. Most of the interest in the 1825 election understandably focused on the selection of a site for the capital. Two factions vied for power in choosing the site, with one pushing for Cahawba and the other pushing for Tuscaloosa. The southern site was associated with the arrogant actions of Gov. William Wyatt Bibb, who had ignored a legislative commission recommendation to place the capital at Tuscaloosa in 1819. Sectional interests were paramount when northern and west-central Alabama legislators gained a narrow ascendancy in the legislature in the 1825 election. Murphy, like Pickens, was a south Alabamian who opposed the move from Cahawba, but as a realist without a veto, he did not fight the effort, and Tuscaloosa was chosen. Cahawba continued to flourish for several decades, but by the late nineteenth century, the community had all but vanished.

Old Cahawba Centennial Monument

The dominance of the Pickens forces was so great that Murphy was twice elected governor without opposition (in 1825 and 1827). The most important development in his first term was the decision to move the capital from Cahawba to Tuscaloosa. The 1819 Constitution provided for the first session of the legislature to be held in Huntsville and “all subsequent sessions at the town of Cahawba” until 1825, when legislators could “designate by law . . . the permanent seat of Government” without the need for concurrence by the governor. Most of the interest in the 1825 election understandably focused on the selection of a site for the capital. Two factions vied for power in choosing the site, with one pushing for Cahawba and the other pushing for Tuscaloosa. The southern site was associated with the arrogant actions of Gov. William Wyatt Bibb, who had ignored a legislative commission recommendation to place the capital at Tuscaloosa in 1819. Sectional interests were paramount when northern and west-central Alabama legislators gained a narrow ascendancy in the legislature in the 1825 election. Murphy, like Pickens, was a south Alabamian who opposed the move from Cahawba, but as a realist without a veto, he did not fight the effort, and Tuscaloosa was chosen. Cahawba continued to flourish for several decades, but by the late nineteenth century, the community had all but vanished.

University of Alabama Rotunda, 1859

Tuscaloosa, it turned out, was also the locus of the most important development of Murphy’s second term in office. Murphy’s involvement in events that led to the opening of the University of Alabama began in 1821, when he was elected by the legislature to the university’s first board of trustees. The board’s chairman was Murphy’s friend and colleague, Israel Pickens. Despite urgent requests from the trustees to move forward with the establishment of the institution, Pickens took no action and, in fact, used university endowments to raise capital for his state bank. In his legislative message of November 1827, Murphy urged that the creation of a state university be addressed and that commissioners from each judicial district inspect proposed sites and report back to the legislature. Construction began in Tuscaloosa that year, although the university did not officially open its doors until 1831.

University of Alabama Rotunda, 1859

Tuscaloosa, it turned out, was also the locus of the most important development of Murphy’s second term in office. Murphy’s involvement in events that led to the opening of the University of Alabama began in 1821, when he was elected by the legislature to the university’s first board of trustees. The board’s chairman was Murphy’s friend and colleague, Israel Pickens. Despite urgent requests from the trustees to move forward with the establishment of the institution, Pickens took no action and, in fact, used university endowments to raise capital for his state bank. In his legislative message of November 1827, Murphy urged that the creation of a state university be addressed and that commissioners from each judicial district inspect proposed sites and report back to the legislature. Construction began in Tuscaloosa that year, although the university did not officially open its doors until 1831.

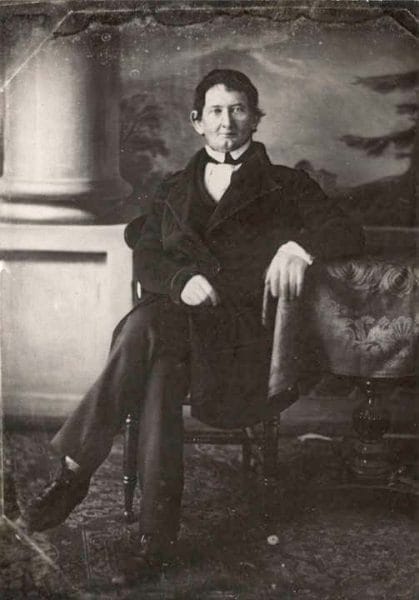

James Dellet

During Murphy’s term as governor, Congress granted the state 400,000 acres of land in north Alabama to be sold to finance the building of canals around the shoals on the Tennessee River, which interrupted transportation. Although some canals were built, they failed to serve their intended purpose because other of the river’s shoals remained unnavigable. In another disappointment and despite his vigorous efforts, Murphy failed to keep a branch of the Bank of the United States from opening in Mobile. This branch, as the governor had feared, ultimately provided disastrous competition to the state Bank of Alabama.

James Dellet

During Murphy’s term as governor, Congress granted the state 400,000 acres of land in north Alabama to be sold to finance the building of canals around the shoals on the Tennessee River, which interrupted transportation. Although some canals were built, they failed to serve their intended purpose because other of the river’s shoals remained unnavigable. In another disappointment and despite his vigorous efforts, Murphy failed to keep a branch of the Bank of the United States from opening in Mobile. This branch, as the governor had feared, ultimately provided disastrous competition to the state Bank of Alabama.

In 1828, Murphy opposed passage of federal legislation known as the “Tariff of Abominations.” The tariff raised the import duties on European goods such as cloth, which was made largely with cotton purchased from southern states. The tariff thus had the effect of reducing exports of U.S. cotton, harming the southern economy. Nevertheless, out of respect for Pres. Andrew Jackson, he did not join South Carolina’s call for nullification of the tariff law and instead worked for reconciliation on this issue. Murphy’s moderate posture on the tariff was, in part, the reason for his defeat by Dixon Hall Lewis, leader of Alabama’s more militant state’s rights group, in the race for the U.S. House of Representatives in 1831.

In 1833, Murphy succeeded in winning a seat in Congress, defeating his former South Carolina College classmate James Dellet. Knowing the political cost of moderation, it is a measure of Murphy’s character that he refused to take extreme positions on such bitterly contested political issues as the question of Creek Indian removal. To avoid open conflict and perhaps bloodshed between the federal government and Alabama, Murphy cooperated with his fellow lawmakers in negotiating a peaceful settlement with the Jackson administration on the Indian question, a settlement that protected Alabama’s claims to sovereignty. His last race for public office, a contest for a U.S. House seat, came in 1839, when he was defeated by Dellet, who had become a leader of the emerging Whig Party in Alabama. Until his death on September 21, 1841, Murphy spent the last years of his life in Clarke County on the plantation he carefully developed.

Note: This entry was adapted with permission from Alabama Governors: A Political History of the State, edited by Samuel L. Webb and Margaret Armbrester (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001).

Further Reading

- Abernathy, Thomas Perkins. The Formative Period in Alabama, 1815-1828. 2d ed. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1965.

- Brantley, William H. Three Capitals: A Book about the First Three Capitals of Alabama: St. Stephens, Huntsville, and Cahawba. 1947. Reprint, Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1976.