Anniston

Downtown Anniston

The city of Anniston, in Calhoun County, emerged as a key industrial center in the mountainous northeastern section of Alabama during the Reconstruction Era. Founders Samuel Noble and Daniel Tyler envisioned the city, situated 60 miles east of Birmingham, as an idealized industrial and conservative Christian community, where workers would earn higher wages than their peers in the North and would resist the temptations of alcohol and gambling. By the early twentieth century, the “Model City” had outgrown the original designs of its creators but remained an important commercial and manufacturing hub.

Downtown Anniston

The city of Anniston, in Calhoun County, emerged as a key industrial center in the mountainous northeastern section of Alabama during the Reconstruction Era. Founders Samuel Noble and Daniel Tyler envisioned the city, situated 60 miles east of Birmingham, as an idealized industrial and conservative Christian community, where workers would earn higher wages than their peers in the North and would resist the temptations of alcohol and gambling. By the early twentieth century, the “Model City” had outgrown the original designs of its creators but remained an important commercial and manufacturing hub.

The establishment and growth of Fort McClellan and the Anniston Army Depot during the First and the Second World Wars boosted the city’s social life and economic status, luring in thousands of new residents. During the second half of the twentieth century, however, civil rights clashes, economic decline, environmental contamination from a local chemical plant, and the construction of a chemical weapons incinerator at the Army Depot presented fresh challenges to Anniston residents.

Early History

Anniston’s roots can be traced back to 1851, when industrialist James Noble Sr., father of Samuel Noble, visited his native country of England, where he attended the Crystal Palace Exposition in London. Strolling through the various exhibits, Noble came across samples of hematite ore from the southeastern United States that he judged far superior to the product he regularly used at his iron foundry in Reading, Pennsylvania. This, coupled with the region’s favorable climate, persuaded him to seek his fortunes in the South. In 1855, Noble and his family relocated to Rome, Georgia, and built one of the largest iron-producing companies south of Richmond. During the Civil War, the Noble Brothers and Company facility produced weaponry for the Confederacy until its capture and subsequent destruction by Federal troops in 1864. After the war, the Nobles secured enough capital to rebuild the foundries in Rome.

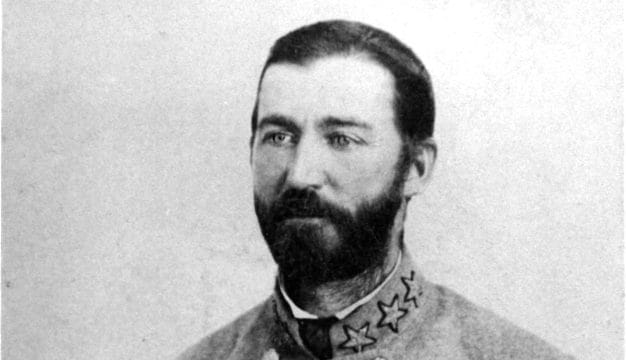

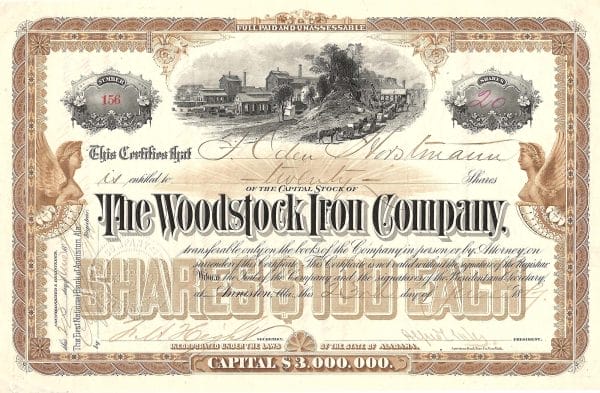

Woodstock Iron Company Certificate

In 1871, seeking to expand their iron enterprises into Alabama, the Nobles acquired hundreds of acres of prime timber and ore land in southern Calhoun County, near the town of Oxford, and devised plans for a new furnace. During a business trip to Charleston, South Carolina, Samuel Noble met Daniel Tyler, a former Union general and native of Connecticut. In need of additional investors, Noble invited Tyler to tour the family’s newly acquired properties in Alabama. Tyler apparently liked what he saw. On April 29, 1872, representatives from both families convened in Rome, drew up a contract, and officially established the Woodstock Iron Company. Within a year, a small village, also called Woodstock, sprang up around the new furnace in Calhoun County. By the summer of 1873, the Woodstock furnace had become fully operational, producing 120 to 150 tons of pig iron per week. Upon discovery that another village named Woodstock already existed in central Alabama, town officials changed the name to Anniston in 1873 in honor of Daniel Tyler’s daughter-in-law, Annie Tyler.

Woodstock Iron Company Certificate

In 1871, seeking to expand their iron enterprises into Alabama, the Nobles acquired hundreds of acres of prime timber and ore land in southern Calhoun County, near the town of Oxford, and devised plans for a new furnace. During a business trip to Charleston, South Carolina, Samuel Noble met Daniel Tyler, a former Union general and native of Connecticut. In need of additional investors, Noble invited Tyler to tour the family’s newly acquired properties in Alabama. Tyler apparently liked what he saw. On April 29, 1872, representatives from both families convened in Rome, drew up a contract, and officially established the Woodstock Iron Company. Within a year, a small village, also called Woodstock, sprang up around the new furnace in Calhoun County. By the summer of 1873, the Woodstock furnace had become fully operational, producing 120 to 150 tons of pig iron per week. Upon discovery that another village named Woodstock already existed in central Alabama, town officials changed the name to Anniston in 1873 in honor of Daniel Tyler’s daughter-in-law, Annie Tyler.

Anniston originated as a planned private community. Noble and Tyler began by laying out the city streets in a perfect checkerboard fashion. Next, they meticulously designed the cityscape, down to the planting of oak trees along Quintard Avenue, which can still be found there. At first, the pair limited the number of settlers and maintained a strict “closed-door policy,” going so far as to erect a fence around their properties to ward off outsiders. They claimed that by doing so, they could lay out the town according to their own desires, without the competing interests of diverse economic classes.

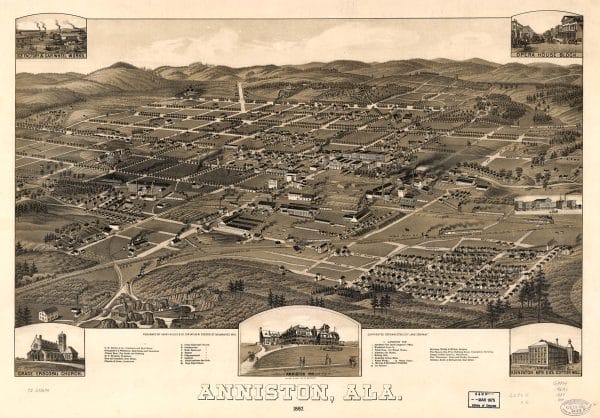

Anniston, 1887

The Woodstock Company constructed parks, worker housing, a sewer system, a company store, churches, and schools. To foster this idealized company town, they hand selected residents, paid them above-average wages, housed them in tidy four-room cottages, and banned alcohol. As a result of the company’s closed-door policy, Anniston’s population remained relatively low in the early years. By 1880, only 942 people resided within the city. Just over two-thirds of the residents were white—a ratio that would not change until the latter half of the twentieth century. Most of the residents were recruited from Alabama and Georgia, but a number of skilled artisans were brought in from England, Sweden, and Poland. A majority of the men, both white and black, were employed at Woodstock Iron, where they toiled at the furnaces, extracted ore from the surrounding hillsides, and cut timber to be used as charcoal. In 1879, the Noble and Tyler families established a cotton mill in the city, the Anniston Manufacturing Company, which employed many of the wives and children of white furnace workers. African American women, if they could find work, were typically employed as domestic servants or laundry workers. Initially, a significant number of working-class blacks and whites resided in the same neighborhoods, following the same paths to work each morning. Strict racial segregation would not be imposed in the city until the 1890s.

Anniston, 1887

The Woodstock Company constructed parks, worker housing, a sewer system, a company store, churches, and schools. To foster this idealized company town, they hand selected residents, paid them above-average wages, housed them in tidy four-room cottages, and banned alcohol. As a result of the company’s closed-door policy, Anniston’s population remained relatively low in the early years. By 1880, only 942 people resided within the city. Just over two-thirds of the residents were white—a ratio that would not change until the latter half of the twentieth century. Most of the residents were recruited from Alabama and Georgia, but a number of skilled artisans were brought in from England, Sweden, and Poland. A majority of the men, both white and black, were employed at Woodstock Iron, where they toiled at the furnaces, extracted ore from the surrounding hillsides, and cut timber to be used as charcoal. In 1879, the Noble and Tyler families established a cotton mill in the city, the Anniston Manufacturing Company, which employed many of the wives and children of white furnace workers. African American women, if they could find work, were typically employed as domestic servants or laundry workers. Initially, a significant number of working-class blacks and whites resided in the same neighborhoods, following the same paths to work each morning. Strict racial segregation would not be imposed in the city until the 1890s.

By 1880, Anniston’s future as an industrial center seemed assured. The Nobles and Tylers formulated plans to expand the iron furnaces and relocate many of the family holdings in Rome, such as the Noble Brothers Wheel Works, to the growing city. In 1883, believing that their vision for the city was assured, the proprietors of Woodstock Iron opened the town to the public, allowing outside investors and entrepreneurs to enter the community for the first time, purchase vacant lots, and establish various commercial and industrial firms. Chronicling the town’s opening in the Atlanta Constitution, editor Henry Grady dubbed Anniston the “Model City of the New South.” The nickname stuck. Investors, entrepreneurs, and working people from across the South streamed into the new city, prompting a building boom that would help stimulate the local economy for nearly a decade. By 1890, more than 9,000 people called Anniston home. Most of the black and white residents lived on the west side of Noble Street, the city’s main thoroughfare, and worked at one of Anniston’s numerous manufacturing firms. By 1890, the original Noble and Tyler enterprises, such as Woodstock Iron and the Anniston Manufacturing Company, had been joined by several new ones, including the Hercules Pipe Company and the Anniston Pipe & Foundry Company, further diversifying a growing local economy. Many wealthy and influential whites, such as attorney J. J. Willett and future governor Thomas Kilby, entered the community during this period of growth, building their homes on the east side of the city, far removed from the smoke and noise of the manufacturing sector. Economic depression in the 1890s slowed the city’s growth, but the temporary establishment of Camp Shipp during the Spanish-American War helped revive the local economy. In 1899, the city replaced Jacksonville as the seat of Calhoun County.

The Twentieth Century

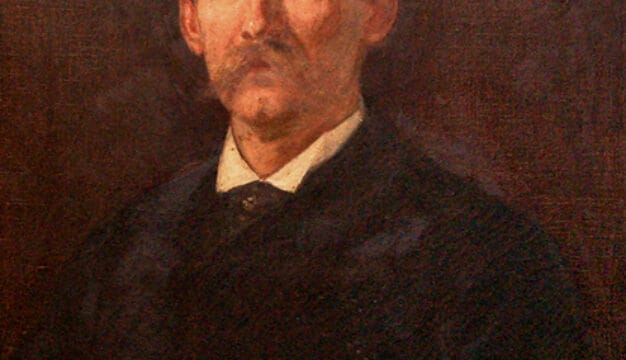

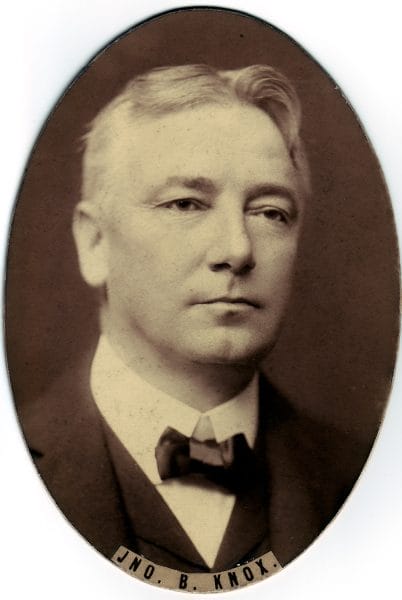

Knox, John B.

By the twentieth century, Anniston was one of the leading industrial cities in Alabama, producing everything from cotton textiles to locomotive brakes. The city also earned a second nickname, “the soil pipe capital of the world,” for its production of sewer pipes, and by the 1940s, one of Anniston’s leading manufacturing firms, the Alabama Pipe Company, annually produced 22 percent of the nation’s cast-iron sewer pipe. The city’s political profile rose as well. Anniston attorney John B. Knox presided over the Constitutional Convention of 1901, and in 1918, Thomas Kilby, a leading industrialist and former mayor of Anniston, was elected governor of Alabama.

Knox, John B.

By the twentieth century, Anniston was one of the leading industrial cities in Alabama, producing everything from cotton textiles to locomotive brakes. The city also earned a second nickname, “the soil pipe capital of the world,” for its production of sewer pipes, and by the 1940s, one of Anniston’s leading manufacturing firms, the Alabama Pipe Company, annually produced 22 percent of the nation’s cast-iron sewer pipe. The city’s political profile rose as well. Anniston attorney John B. Knox presided over the Constitutional Convention of 1901, and in 1918, Thomas Kilby, a leading industrialist and former mayor of Anniston, was elected governor of Alabama.

During World War I, the U.S. Army established Camp McClellan north of the city, beginning Anniston’s ongoing relationship with the U.S. military. In 1929, at the behest of Anniston Star publisher Harry Mell Ayers and others, the government re-christened the camp Fort McClellan and gave it permanent status. During World War II, the fort witnessed an extensive rebuilding project, as barracks, latrines, officers’ quarters, and similar facilities were constructed for the roughly half million troops who would ultimately train there during the conflict. A prisoner-of-war camp was added to Fort McClellan in 1943.

Fort McClellan

The war brought additional economic development to Anniston. Millions of dollars from the federal government poured into the city to buy war-related material, such as artillery shells and cartridge cases, lifting employment levels and boosting production at the Anniston Foundry Company, Kilby Steel, and other plants. Thousands of people flocked to the city to find work in one of the mills or foundries, or at the new Anniston Army Depot, built on the outskirts of the city in 1941 to store ammunition, and managed by the Chrysler Corporation from 1943 to 1945. In 1930, Anniston’s metro population stood at just 22,345. By 1940, the number had risen to 25,523 in the city and 68,000 across the entire metro area. During the 1950s and 1960s, the city’s industrial and military sectors continued to grow, evidenced by the addition of a Chemical Corps training facility at Fort McClellan and the expansion of the Anniston Army Depot. By the mid-1960s, Anniston’s population exceeded 33,000, with more than 100,000 people residing within the metropolitan area.

Fort McClellan

The war brought additional economic development to Anniston. Millions of dollars from the federal government poured into the city to buy war-related material, such as artillery shells and cartridge cases, lifting employment levels and boosting production at the Anniston Foundry Company, Kilby Steel, and other plants. Thousands of people flocked to the city to find work in one of the mills or foundries, or at the new Anniston Army Depot, built on the outskirts of the city in 1941 to store ammunition, and managed by the Chrysler Corporation from 1943 to 1945. In 1930, Anniston’s metro population stood at just 22,345. By 1940, the number had risen to 25,523 in the city and 68,000 across the entire metro area. During the 1950s and 1960s, the city’s industrial and military sectors continued to grow, evidenced by the addition of a Chemical Corps training facility at Fort McClellan and the expansion of the Anniston Army Depot. By the mid-1960s, Anniston’s population exceeded 33,000, with more than 100,000 people residing within the metropolitan area.

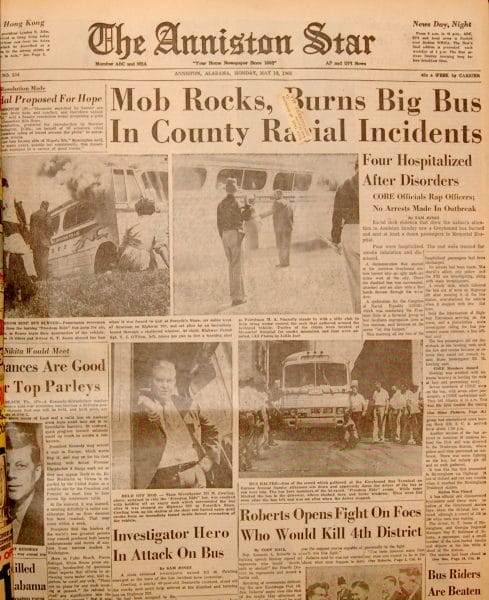

Anniston Star

In May 1961, Anniston garnered international media attention when area Klansmen halted and burned a Greyhound bus carrying Congress of Racial Equality Freedom Riders, who were testing a recent Supreme Court decision banning segregated bus facilities along interstate routes. Following another round of racial violence in 1963, Mayor Claude Dear and his fellow city commissioners created the biracial Human Relations Council to foster better race relations and pave the way for the eventual desegregation of area schools and businesses. By 1965, legal segregation had ended in the Model City, and several African American students had crossed the color barrier at Anniston High School. In 1971, when racial conflict again arose, representatives from the black and white communities formed the Community of Unified Leadership (COUL), which did much to heal the racial divide by creating job-training programs and convincing downtown shops to hire African American employees in front-end positions.

Anniston Star

In May 1961, Anniston garnered international media attention when area Klansmen halted and burned a Greyhound bus carrying Congress of Racial Equality Freedom Riders, who were testing a recent Supreme Court decision banning segregated bus facilities along interstate routes. Following another round of racial violence in 1963, Mayor Claude Dear and his fellow city commissioners created the biracial Human Relations Council to foster better race relations and pave the way for the eventual desegregation of area schools and businesses. By 1965, legal segregation had ended in the Model City, and several African American students had crossed the color barrier at Anniston High School. In 1971, when racial conflict again arose, representatives from the black and white communities formed the Community of Unified Leadership (COUL), which did much to heal the racial divide by creating job-training programs and convincing downtown shops to hire African American employees in front-end positions.

Challenges in the Post-Civil Rights Era

The decade of the 1970s saw many positive developments in the city. In 1972, the renowned Alabama Shakespeare Festival was founded in Anniston. It operated in the city until its relocation to Montgomery in 1985. In 1977, citing its deft management of racial crises in the 1960s and 1970s and its progressive nature, the National Civil League named Anniston an All-American City.

By the 1980s and 1990s, however, a stagnant economy, a lack of commercial and industrial diversification, the impending closure of Fort McClellan, PCB contamination from the local Monsanto (now Solutia) plant, and the proposed construction of a chemical weapons incinerator at the Anniston Army Depot had left the Model City’s economic future in doubt. Many of the factories and mills that had employed thousands and gained the city a reputation for progress and efficiency, such as the Anniston Cordage Company, had been shut down or gutted. A market shift to plastic piping in the 1970s and a general decline in the heavy-metal and concrete industries, as foreign firms became more competitive, further damaged Anniston’s economy. By 1993, unemployment rates in the city had inched above 17 percent (Calhoun County’s unemployment rate stood at 9 percent).

In 1995, the Base Realignment and Closure Committee (BRAC) voted to close Fort McClellan, sending panic waves through the community. Despite a concerted effort by local officials to keep it open, the fort officially closed its doors in May 1999, leaving much uncertainty in its wake.

Anniston Today

Anniston Chemical Agent Disposal Facility

In the twenty-first century, Anniston still struggles to overcome its environmental and economic woes. For 50 years, the Monsanto Corporation manufactured polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) in the city for use as insulation in electrical equipment and appliances. As a result, high levels of PCB contamination have been detected in neighborhoods surrounding the plant. Countless residents have reported myriad health problems, including cancer, headaches, low IQ scores in children, and respiratory distress, which they blame on the PCBs. Class-action suits were brought against the company in the late 1990s, involving more than 20,000 residents. In 2003, the plaintiffs reached a settlement with Monsanto/Solutia worth more than $600 million. That same year, in a highly controversial move, the Army began incinerating more than 2,200 tons of chemical weapons that had been stored at the Anniston Army Depot since the 1960s. Officials estimated that it would take approximately a decade to eliminate the chemical stockpile, which included sarin and mustard gas. Disposal was completed in 2014, and the site was closed down.

Anniston Chemical Agent Disposal Facility

In the twenty-first century, Anniston still struggles to overcome its environmental and economic woes. For 50 years, the Monsanto Corporation manufactured polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) in the city for use as insulation in electrical equipment and appliances. As a result, high levels of PCB contamination have been detected in neighborhoods surrounding the plant. Countless residents have reported myriad health problems, including cancer, headaches, low IQ scores in children, and respiratory distress, which they blame on the PCBs. Class-action suits were brought against the company in the late 1990s, involving more than 20,000 residents. In 2003, the plaintiffs reached a settlement with Monsanto/Solutia worth more than $600 million. That same year, in a highly controversial move, the Army began incinerating more than 2,200 tons of chemical weapons that had been stored at the Anniston Army Depot since the 1960s. Officials estimated that it would take approximately a decade to eliminate the chemical stockpile, which included sarin and mustard gas. Disposal was completed in 2014, and the site was closed down.

Centennial Memorial Park

With the lawsuits settled and the environmental cleanup underway, Anniston’s 24,000 residents hope for a brighter future. Since the early 1990s, the Spirit of Anniston Main Street Program, Inc., which was created by local business leaders to revitalize the old downtown shopping district, has worked successfully to preserve historical landmarks, refurbish storefronts, and attract new businesses to Noble Street. Following the closure of Fort McClellan in 1999, the Joint Powers Authority and the city of Anniston began working to redevelop the facility for civilian use. Today, more than 300 families reside in the newly christened McClellan, an 18,000-acre planned community. Several business firms and educational facilities, such as Lowe’s and the Jacksonville State Higher Education Consortium, have opened their doors on the former military base, with promises of more to follow.

Centennial Memorial Park

With the lawsuits settled and the environmental cleanup underway, Anniston’s 24,000 residents hope for a brighter future. Since the early 1990s, the Spirit of Anniston Main Street Program, Inc., which was created by local business leaders to revitalize the old downtown shopping district, has worked successfully to preserve historical landmarks, refurbish storefronts, and attract new businesses to Noble Street. Following the closure of Fort McClellan in 1999, the Joint Powers Authority and the city of Anniston began working to redevelop the facility for civilian use. Today, more than 300 families reside in the newly christened McClellan, an 18,000-acre planned community. Several business firms and educational facilities, such as Lowe’s and the Jacksonville State Higher Education Consortium, have opened their doors on the former military base, with promises of more to follow.

Demographics

According to 2020 Census estimates, Anniston recorded a population of 21,518. Of that number, 52.3 percent identified themselves as African American, 43.8 percent as white, 3.8 percent as Hispanic or Latino, 2.5 as two or more races, 0.8 percent as Asian, and 0.3 percent as American Indian. The median household income was estimated at $41,366, and the per capita income was $27,651.

Employment

According to 2020 Census estimates, the workforce in Anniston was divided among the following industrial categories:

- Manufacturing (22.6 percent)

- Educational services, and health care and social assistance (21.9 percent)

- Arts, entertainment, recreation, and accommodation and food services (10.6 percent)

- Retail trade (10.4 percent)

- Professional, scientific, management, and administrative and waste management services (8.3 percent)

- Public administration (6.6 percent)

- Construction (4.8 percent)

- Other services, except public administration (4.6 percent)

- Transportation and warehousing and utilities (4.6 percent)

- Finance, insurance, and real estate, rental, and leasing (2.6 percent)

- Wholesale trade (2.0 percent)

- Information (0.7 percent)

- Agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting, and extractive (0.3 percent)

Education

Schools in Anniston are part of the Anniston City School System; the town has five elementary schools, one middle school, and one high school.

Transportation

Interstate 20 runs east-west along the southern edge of the city, State Highway 202 runs west out of the city, and U.S. Highway 431 runs north-south through the center of the city. McMinn Airport, located in the northern part of the city, serves general aviation.

Events and Places of Interest

Egyptian Mummies at the Anniston Museum of Natural History

Anniston Museums and Gardens comprises the Anniston Museum of Natural History, which features exhibits on geology, Alabama’s natural environment and wildlife, African environments, and ancient Egypt and provides educational programming and traveling exhibits, and the Berman Museum of World History, which houses artifacts, art, photographs, and dioramas relating to the world’s cultures. During the summer, Fort McClellan hosts Music at McClellan, a weekly concert series featuring jazz, rock, classical, and other genres of music at the historic Monteith Amphitheater, built in 1937. And the Knox Concert Series, held at the Anniston Performing Arts Center, offers a wide variety of musical performances, including classical, Broadway musicals, and popular performers. C.A.S.T. (the Community Actors Studio Theater) offers a wide variety of theatrical performances throughout the year. Visitors interested in the visual arts can tour Artworks Gallery, a cooperative that features the works of local artists.

Egyptian Mummies at the Anniston Museum of Natural History

Anniston Museums and Gardens comprises the Anniston Museum of Natural History, which features exhibits on geology, Alabama’s natural environment and wildlife, African environments, and ancient Egypt and provides educational programming and traveling exhibits, and the Berman Museum of World History, which houses artifacts, art, photographs, and dioramas relating to the world’s cultures. During the summer, Fort McClellan hosts Music at McClellan, a weekly concert series featuring jazz, rock, classical, and other genres of music at the historic Monteith Amphitheater, built in 1937. And the Knox Concert Series, held at the Anniston Performing Arts Center, offers a wide variety of musical performances, including classical, Broadway musicals, and popular performers. C.A.S.T. (the Community Actors Studio Theater) offers a wide variety of theatrical performances throughout the year. Visitors interested in the visual arts can tour Artworks Gallery, a cooperative that features the works of local artists.

Silver Lakes Golf Course

Mountain Longleaf National Wildlife Refuge, located on the former Fort McClellan Army Base, is home to one of the last remaining stands of longleaf pine forest in the state. Other outdoor recreational opportunities include the Chief Ladiga Trail, a 33-mile rails-to-trails project that joins Anniston with the cities of Piedmont, Jacksonville, and Weaver. There are also stops on the North Alabama Birding Trail in and around Anniston. The Coldwater Mountain Bike Trail is located in the 4,000-acre Coldwater Mountain Forever Wild Tract. And the city is home to seven golf courses, including the Silver Lakes stop on the Robert Trent Jones Golf Trail. In June 2016, the city established a civil rights trail to highlight important locations associated with the civil rights movement.

Silver Lakes Golf Course

Mountain Longleaf National Wildlife Refuge, located on the former Fort McClellan Army Base, is home to one of the last remaining stands of longleaf pine forest in the state. Other outdoor recreational opportunities include the Chief Ladiga Trail, a 33-mile rails-to-trails project that joins Anniston with the cities of Piedmont, Jacksonville, and Weaver. There are also stops on the North Alabama Birding Trail in and around Anniston. The Coldwater Mountain Bike Trail is located in the 4,000-acre Coldwater Mountain Forever Wild Tract. And the city is home to seven golf courses, including the Silver Lakes stop on the Robert Trent Jones Golf Trail. In June 2016, the city established a civil rights trail to highlight important locations associated with the civil rights movement.

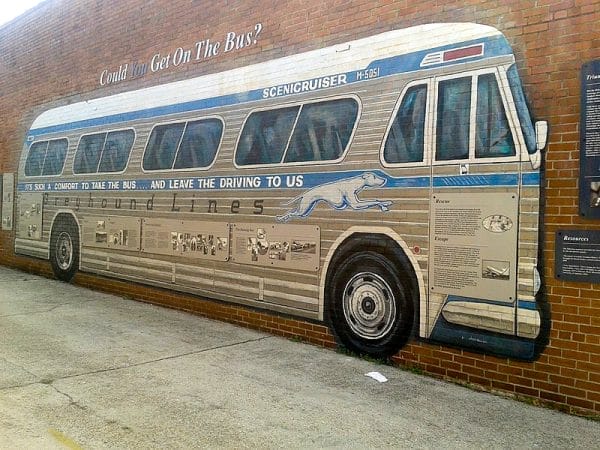

Freedom Rider Mural

Anniston has more than 40 properties on the National Register of Historic Places, including several related to founder Samuel Noble, the city’s military history, and its industrial history. There are 16 properties in Anniston listed on the Alabama Register of Landmarks and Heritage, including the Noble-Woodruff House (c. 1882), the Borders House (c. 1840), and the Lyric Theatre (c. 1918). In January 2017, Pres. Barack Obama designated the former Greyhound bus station, where white supremacists had boarded the Greyhound bus, and the site where the bus was burned outside of Anniston, to be the Freedom Riders National Monument. Centennial Memorial Park honors Alabamians killed in service to their country and is the official state veteran’s memorial.

Freedom Rider Mural

Anniston has more than 40 properties on the National Register of Historic Places, including several related to founder Samuel Noble, the city’s military history, and its industrial history. There are 16 properties in Anniston listed on the Alabama Register of Landmarks and Heritage, including the Noble-Woodruff House (c. 1882), the Borders House (c. 1840), and the Lyric Theatre (c. 1918). In January 2017, Pres. Barack Obama designated the former Greyhound bus station, where white supremacists had boarded the Greyhound bus, and the site where the bus was burned outside of Anniston, to be the Freedom Riders National Monument. Centennial Memorial Park honors Alabamians killed in service to their country and is the official state veteran’s memorial.

Further Reading

- Gates, Grace Hooten. The Model City of the New South: Anniston, Alabama, 1872-1900. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1978.

- Love, Dennis. My City Was Gone: One American Town’s Toxic Secret, Its Angry Band of Locals, and a $700 Million Day in Court. New York: HarperCollins, 2006.

- Noble, Phil. Beyond the Burning Bus: The Civil Rights Revolution in a Southern Town. Montgomery: New South Books, 2003.

- Sprayberry, Gary S. “‘Town Among the Trees’: Paternalism, Class, and Civil Rights in Anniston, Alabama, 1872 to Present.” Ph.D diss., University of Alabama, 2003.