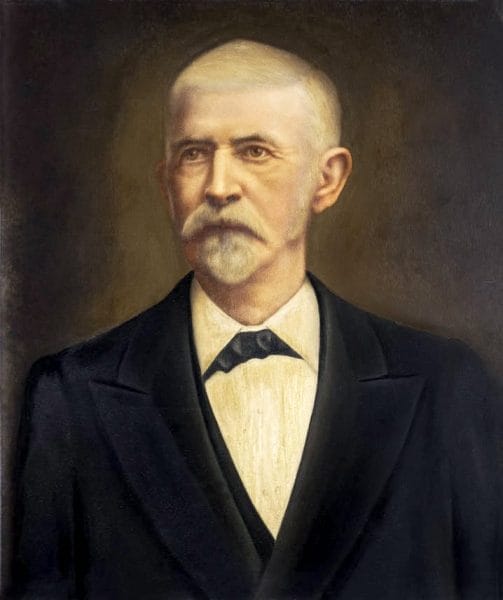

Edward A. O'Neal (1882-86)

Edward A. O’Neal

Edward Asbury O’Neal (1818-1890) continued the line of pro-secession, faithful Confederate, Bourbon governors who controlled the executive branch of Alabama in the late nineteenth century. O’Neal’s parents, Edward and Rebecca O’Neal, moved to Madison County, Alabama, from South Carolina, shortly before he was born on September 20, 1818. Edward attended Green Academy in Huntsville and in 1836 graduated with honors from LaGrange College. In that same year, he married Olivia Moore, the daughter of a prominent Madison County family, and they established a home in Florence, Lauderdale County, with their nine children.

Edward A. O’Neal

Edward Asbury O’Neal (1818-1890) continued the line of pro-secession, faithful Confederate, Bourbon governors who controlled the executive branch of Alabama in the late nineteenth century. O’Neal’s parents, Edward and Rebecca O’Neal, moved to Madison County, Alabama, from South Carolina, shortly before he was born on September 20, 1818. Edward attended Green Academy in Huntsville and in 1836 graduated with honors from LaGrange College. In that same year, he married Olivia Moore, the daughter of a prominent Madison County family, and they established a home in Florence, Lauderdale County, with their nine children.

In the antebellum period, O’Neal became increasingly active in politics. Slight in stature, O’Neal’s youth was marked by tremendous energy and enthusiasm for his causes, although his political opponents described him as lacking “force of mind and character.” He loved pomp and parade and most described him as an excellent speaker. O’Neal studied law in Huntsville, was admitted to the Alabama State Bar, and in the 1840s established a successful practice in Florence, serving as legal representative for northwest Alabama’s large plantation and textile mill owners. Before making an unsuccessful run for the U.S. Congress in 1848, O’Neal served as solicitor of the Fourth Circuit. He was a states’ rights Democrat who actively encouraged secession and celebrated the firing on Fort Sumter, South Carolina.

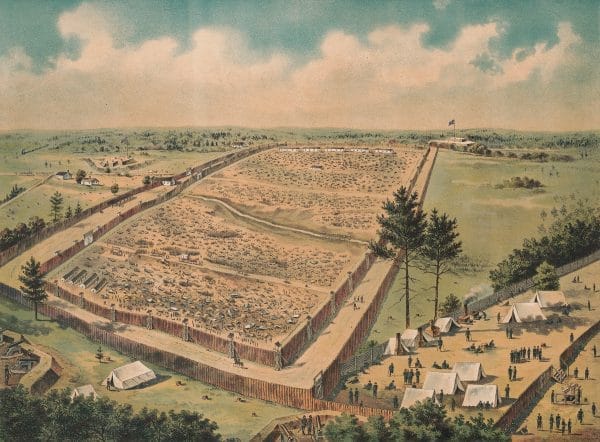

Andersonville Prison

After that event, O’Neal raised a company for the Ninth Alabama Infantry Regiment. In March 1862, he received a commission as colonel of the 26th Alabama Infantry Regiment, which was assigned to Gen. Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia and participated in many of the major battles of the Civil War, including Seven Pines, Seven Days, Chancellorsville, and Gettysburg. The 26th Infantry was noted for its valor and bravery and suffered very high casualty rates. O’Neal was wounded twice in two separate battles and was one of the original commanders of the guards at the infamous Andersonville Prison in Americus, Georgia. He and the 26th later joined southern troops in the defense of Atlanta during Union general William Tecumseh Sherman’s attack. The decimated company consolidated with other Alabama regiments that surrendered at Greensboro, North Carolina, in 1865. Only after O’Neal’s surrender did the Confederacy award him a commission as brigadier general promised during the war, but he never received it nor officially accepted it. The state of Alabama later issued him a legitimate commission as brigadier general.

Andersonville Prison

After that event, O’Neal raised a company for the Ninth Alabama Infantry Regiment. In March 1862, he received a commission as colonel of the 26th Alabama Infantry Regiment, which was assigned to Gen. Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia and participated in many of the major battles of the Civil War, including Seven Pines, Seven Days, Chancellorsville, and Gettysburg. The 26th Infantry was noted for its valor and bravery and suffered very high casualty rates. O’Neal was wounded twice in two separate battles and was one of the original commanders of the guards at the infamous Andersonville Prison in Americus, Georgia. He and the 26th later joined southern troops in the defense of Atlanta during Union general William Tecumseh Sherman’s attack. The decimated company consolidated with other Alabama regiments that surrendered at Greensboro, North Carolina, in 1865. Only after O’Neal’s surrender did the Confederacy award him a commission as brigadier general promised during the war, but he never received it nor officially accepted it. The state of Alabama later issued him a legitimate commission as brigadier general.

Four years to the day after O’Neal left Florence for the war, he returned, resumed his law practice, and became a tireless worker in the Democratic Party. He nominated Robert Burns Lindsay for governor at the state Democratic convention in 1870, contributed to the effort to return the Democrats to power during Reconstruction, and played a prominent role in the state constitutional convention of 1875, where he chaired the committee on education. In the 1880 presidential election, he served as a statewide elector for the Democratic candidate.

Isaac Harvey Vincent

In a carefully managed campaign conducted over several months, O’Neal’s name was placed in newspapers as a possible candidate for the 1882 gubernatorial nomination. He was touted for his role in defeating Republicans and ending Reconstruction, and north Alabama voters insisted that it was their time to hold the governorship again. O’Neal’s Confederate military activities also received wide attention, and at the June convention he received the nomination and won the 1882 election easily. The only event attracting national attention during O’Neal’s administration involved Isaac “Honest Ike” Harvey Vincent, who in 1882 was reelected for an unprecedented third term as Alabama’s state treasurer. In late January 1883, Vincent’s clerk informed him that the state auditor’s office would begin an examination of his records the next day. Vincent took the first train out of town that night, having stolen $200,000 in state funds. At first, O’Neal did not realize that Vincent was a fugitive, but when he learned of an $8,000 overdraft in the state’s bank account, he hired the Pinkerton detective agency to find Vincent. Although the agency failed to locate him despite following leads from Canada to Mexico, several years later Vincent was discovered in Texas and returned to Alabama for trial, during which he was convicted of embezzlement. O’Neal began legal proceedings to recover the lost funds, but because of mishandled or lost paperwork dealing with Vincent’s bond, the state recovered only a small portion of the monies.

Isaac Harvey Vincent

In a carefully managed campaign conducted over several months, O’Neal’s name was placed in newspapers as a possible candidate for the 1882 gubernatorial nomination. He was touted for his role in defeating Republicans and ending Reconstruction, and north Alabama voters insisted that it was their time to hold the governorship again. O’Neal’s Confederate military activities also received wide attention, and at the June convention he received the nomination and won the 1882 election easily. The only event attracting national attention during O’Neal’s administration involved Isaac “Honest Ike” Harvey Vincent, who in 1882 was reelected for an unprecedented third term as Alabama’s state treasurer. In late January 1883, Vincent’s clerk informed him that the state auditor’s office would begin an examination of his records the next day. Vincent took the first train out of town that night, having stolen $200,000 in state funds. At first, O’Neal did not realize that Vincent was a fugitive, but when he learned of an $8,000 overdraft in the state’s bank account, he hired the Pinkerton detective agency to find Vincent. Although the agency failed to locate him despite following leads from Canada to Mexico, several years later Vincent was discovered in Texas and returned to Alabama for trial, during which he was convicted of embezzlement. O’Neal began legal proceedings to recover the lost funds, but because of mishandled or lost paperwork dealing with Vincent’s bond, the state recovered only a small portion of the monies.

During this affair, additional accounting irregularities were discovered in other departments, which led the legislature to create the office of Examiner of Accounts. The first state examiner, James W. Lapsley, found and corrected numerous errors and saved the state thousands of dollars. O’Neal recommended that a bond be required of all future state treasurers, but the state did not regularly enforce this requirement until 1898.

O’Neal’s first term was marked by a small increase in state spending and the use of state troops to put down labor unrest in Opelika and Birmingham, which earned him criticism. Although south Alabama threw its support behind John M. McKleroy of Barbour County, O’Neal received the nomination of his party for a second term. Despite some censure of him because of the Vincent affair, O’Neal easily won a second term in 1884. The Republican Party offered no opposition, and in some counties, such as Montgomery, the party ordered its black members not to vote at all.

O’Neal took a particular interest in education, but he was equally determined to limit state spending. During his terms, the Agricultural and Mechanical College (now Auburn University) at Auburn expanded its departments, and state normal schools for the training of white teachers opened at Jacksonville and Livingston. The number of elementary and secondary public schools expanded, and according to O’Neal, more Alabama children were receiving an education than at any time since the establishment of public education. Yet in 1883, the total state budget for education was $130,000, and spending per child in Alabama remained among the lowest of any state in the nation.

After receiving reports of high mortality rates at mines using convict labor leased from Alabama’s state and county prisons, O’Neal ordered health inspections in 1883. Convicts lived in unsanitary conditions that bred diseases, were treated with cruelty and unrelenting work demands, and were provided with insufficient food. Inspections increased, but legislation pushed through the state legislature by Warden John Hollis Bankhead required all prisoners to be leased to three mining companies and made inspection reporting optional. Thus conditions actually worsened.

O’Neal’s administrations were sympathetic toward farmers, and he established Alabama’s State Department of Agriculture, appointing Judge Edward C. Betts of Huntsville as its first commissioner. To improve rural life, the state tried to control yellow fever and introduced health and hygiene studies in the curriculum of rural schools.

In the latter part of his administration, O’Neal addressed the problem of state control of local issues. He noted that local legislation absorbed so much of legislators’ time that they neglected the general interest. In addition, many local laws were passed without serious consideration, and O’Neal asserted that it was “possible that no two precincts in the state are living under the same laws.” The legislature did not act on his requests, and the problem of state control of local issues grew worse in the next century.

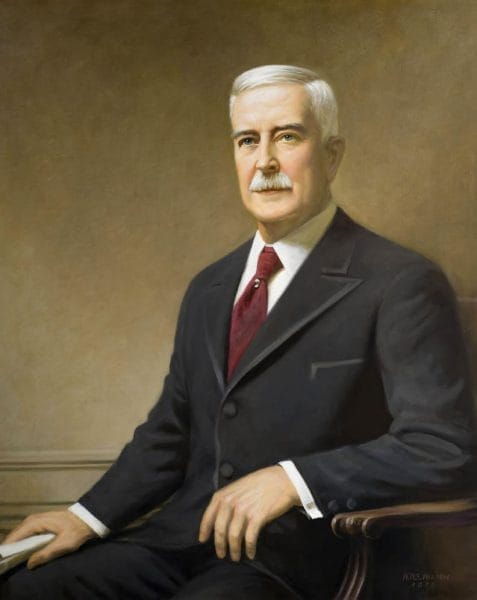

Emmet O’Neal

O’Neal served at a time when the prevailing political ideology opposed strong chief executives, and he was neither an innovative nor controversial governor. The Democratic Party and apparently the populace desired leaders who represented the old order and maintained a safe status quo. O’Neal comfortably fit that requirement. His terms represent a transition between Bourbon redemption and the social and political upheavals of the early 1890s. O’Neal was the first, and so far the only, governor in Alabama history to have a son (Emmet O’Neal) also elected governor. James E. Folsom Jr. served briefly in the position once held by his famous father, but he was not elected to that office. After leaving office, O’Neal retired to Florence; he died at his home on November 7, 1890, and was buried in Florence Cemetery.

Emmet O’Neal

O’Neal served at a time when the prevailing political ideology opposed strong chief executives, and he was neither an innovative nor controversial governor. The Democratic Party and apparently the populace desired leaders who represented the old order and maintained a safe status quo. O’Neal comfortably fit that requirement. His terms represent a transition between Bourbon redemption and the social and political upheavals of the early 1890s. O’Neal was the first, and so far the only, governor in Alabama history to have a son (Emmet O’Neal) also elected governor. James E. Folsom Jr. served briefly in the position once held by his famous father, but he was not elected to that office. After leaving office, O’Neal retired to Florence; he died at his home on November 7, 1890, and was buried in Florence Cemetery.

Note: This entry was adapted with permission from Alabama Governors: A Political History of the State, edited by Samuel L. Webb and Margaret Armbrester (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001).

Further Reading

- Going, Allen J. Bourbon Democracy in Alabama, 1874-1890. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1951.

- Edward A. O’Neal, Administration Papers and Clipping Files, Alabama Department of Archives and History, Montgomery, Alabama.