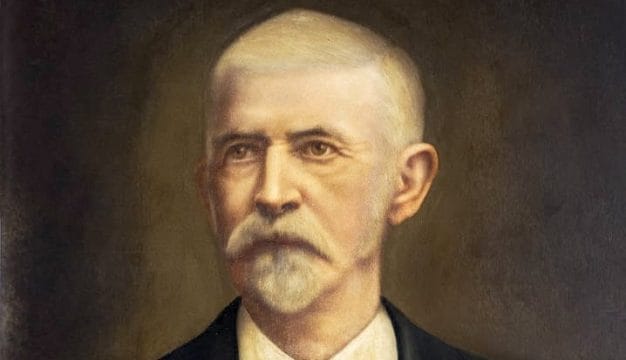

Chauncey Sparks (1943-47)

Chauncey Sparks

Chauncey Sparks (1884-1968) became governor during the height of World War II. He inherited full employment and a surplus in the state treasury from his predecessor. Although he was considered to be fundamentally conservative as he entered the governorship, Sparks was surprisingly progressive on a number of issues, improving funding for education and agricultural research.

Chauncey Sparks

Chauncey Sparks (1884-1968) became governor during the height of World War II. He inherited full employment and a surplus in the state treasury from his predecessor. Although he was considered to be fundamentally conservative as he entered the governorship, Sparks was surprisingly progressive on a number of issues, improving funding for education and agricultural research.

George Chauncey Sparks was born on October 8, 1884, in Barbour County to George Washington Sparks and Sarah E. Castellow Sparks, both natives of Georgia. His father died when Chauncey was two, and the family moved back to Georgia, where the future governor attended local schools in Quitman County. He worked his way through Mercer University in Macon, Georgia, often taking breaks to earn tuition money. He earned a bachelor of arts in 1907 and a law degree in 1910, also from Mercer.

That same year, Sparks returned to Barbour County, passed the Alabama State Bar exam and opened a law office in Eufaula. A few months later, he was appointed judge of the Barbour County inferior court by Gov. Emmet O’Neal, a position that gave him a steady source of income and a title that followed him the rest of his life. He remained on the bench until 1915, when he returned to his law practice. In 1919, he was elected to the Alabama House of Representatives, where he supported Gov. Thomas E. Kilby‘s school program and became Kilby’s assistant floor leader in the House. He chose not to stand for reelection and in 1923 again returned to his law practice and to his farm, where he experimented with raising livestock and poultry as alternatives to growing cotton.

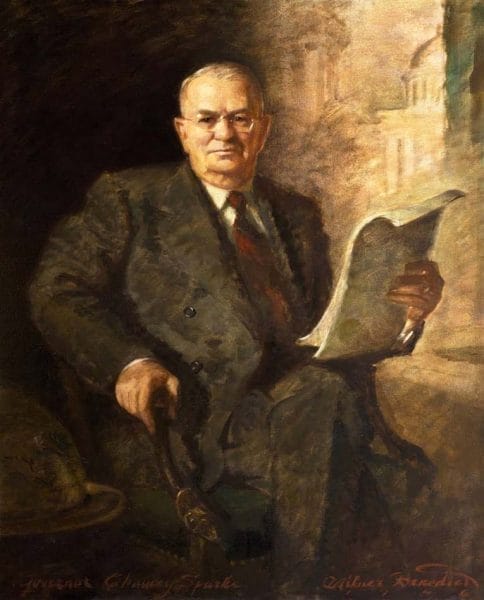

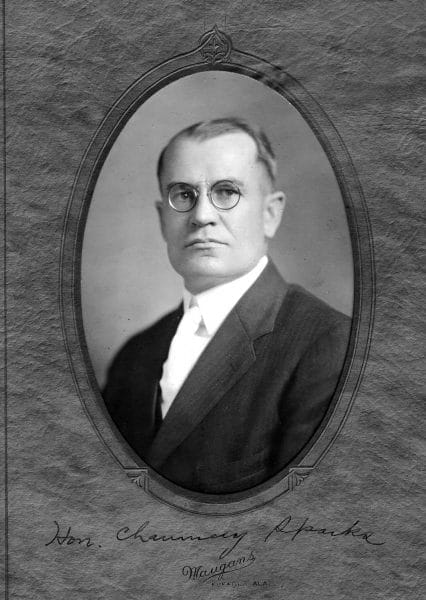

Chauncey Sparks

A lifelong bachelor, Sparks resided with his sister and her family and lived a life during the 1920s that was described as “quiet, careful, and hardworking.” Then in 1930, to the surprise of many, he announced another run for the legislature and was elected. Sparks became an important member of what was described as the “economy bloc,” a group of representatives who fought both income and state sales tax proposals. Furthermore, he sponsored a constitutional amendment to limit salaries of state officials to $6,000 a year and spoke out against waste and for a balanced budget. His leadership in this group earned him the title the “Barbour Bourbon.”

Chauncey Sparks

A lifelong bachelor, Sparks resided with his sister and her family and lived a life during the 1920s that was described as “quiet, careful, and hardworking.” Then in 1930, to the surprise of many, he announced another run for the legislature and was elected. Sparks became an important member of what was described as the “economy bloc,” a group of representatives who fought both income and state sales tax proposals. Furthermore, he sponsored a constitutional amendment to limit salaries of state officials to $6,000 a year and spoke out against waste and for a balanced budget. His leadership in this group earned him the title the “Barbour Bourbon.”

In 1938, Sparks ran for governor against lawyer and war hero Frank Dixon and came in second, but he declined a runoff. Still, the race gave him statewide exposure, and, building on this, he prepared another run for the executive office. Declaring his candidacy in 1942, Sparks faced a number of opponents, including former governor Bibb Graves, who was considered the front-runner, and a young but little known, James E. “Big Jim” Folsom. Almost by default, Sparks found himself the conservative choice, but there was little enthusiasm for his campaign until Graves died. Sparks, now the best-known candidate remaining, immediately became the favorite, and though some liberals tried to rally around Folsom, they were not able to mount a successful challenge. Chauncey Sparks was elected.

The expectation in Montgomery was that Sparks would drastically reduce state spending, but to the surprise of many, the “Barbour Bourbon” became something of a progressive. America was at war, the economy was booming, and tax revenues were up. With wartime restrictions prohibiting big manpower jobs such as highway construction, the governor and legislature were faced with the unique problem of how to spend the state’s surplus. Rejecting efforts by such groups as the Farm Bureau to use the money to reduce property taxes, Governor Sparks launched a series of initiatives that resulted in a host of programs to improve the quality of life for all Alabamians.

Chauncey Sparks Inauguration

Under Sparks, the state appropriation for education was doubled, the school term was lengthened from seven to eight months, appropriations for medical education were doubled, and the Medical College was moved to Birmingham and expanded to a four-year program. A School of Forestry opened at Alabama Polytechnic Institute (Auburn University), and the Tuskegee Institute received an increase in state funding. In addition, appropriations for agricultural programs doubled, and new farm experiment stations opened. Work began on the Garrett Coliseum in Montgomery, and the state Department of Labor, created by Governor Graves and eliminated by Governor Dixon, was reestablished to deal with wartime labor problems. All of this was achieved while reducing the state’s debt by 25 percent. Along with these accomplishments, a constitutional amendment was passed that required the state legislature to meet every two years instead of four.

Chauncey Sparks Inauguration

Under Sparks, the state appropriation for education was doubled, the school term was lengthened from seven to eight months, appropriations for medical education were doubled, and the Medical College was moved to Birmingham and expanded to a four-year program. A School of Forestry opened at Alabama Polytechnic Institute (Auburn University), and the Tuskegee Institute received an increase in state funding. In addition, appropriations for agricultural programs doubled, and new farm experiment stations opened. Work began on the Garrett Coliseum in Montgomery, and the state Department of Labor, created by Governor Graves and eliminated by Governor Dixon, was reestablished to deal with wartime labor problems. All of this was achieved while reducing the state’s debt by 25 percent. Along with these accomplishments, a constitutional amendment was passed that required the state legislature to meet every two years instead of four.

Like so many of his contemporaries, Sparks was an outspoken opponent of “federal encroachments” on the rights of states, particularly in such domestic affairs as race relations. Toward the end of Sparks’ administration, the legislature passed the Boswell Amendment, which limited the increasing number of black voters in the state. The amendment gave county registrars the power to deny suffrage to voters who, in the view of the registrars, did not understand relevant constitutional issues. Governor-elect Folsom spoke out vigorously against its ratification, but to no avail. In a separate issue, Sparks actively fought against the freight rate structure that allowed railroads to discriminate against Alabama and the South.

Always a frugal administrator, the governor delighted and amused Alabamians when they discovered that he was charging his niece, who served as his official hostess, rent for her family’s lodgings in the governor’s mansion. Sparks was not a drinker himself, but he kept fine liquors in the mansion for special occasions and jealously guarded the supply. He is said to have stopped one of his cabinet members from taking a bottle out of the mansion after a party, making him return the stolen goods.

1948 Democratic National Convention

Sparks left office in January 1947, prohibited by the Constitution from succeeding himself as governor. He nevertheless remained active in politics, and the next year represented the state as a delegate to the 1948 Democratic National Convention. When members of a states’ rights faction of the Democrats known as the “Dixiecrats” walked out of the convention in protest of its racially liberal platform, Sparks refused to join them. Remaining with him was a young George Wallace, a fellow Barbour County politician whom Sparks had given his first political job as an assistant state attorney general. Sparks and Wallace remained close friends over the years, and, according to those who knew them, the former governor was “like an uncle” to his young friend.

1948 Democratic National Convention

Sparks left office in January 1947, prohibited by the Constitution from succeeding himself as governor. He nevertheless remained active in politics, and the next year represented the state as a delegate to the 1948 Democratic National Convention. When members of a states’ rights faction of the Democrats known as the “Dixiecrats” walked out of the convention in protest of its racially liberal platform, Sparks refused to join them. Remaining with him was a young George Wallace, a fellow Barbour County politician whom Sparks had given his first political job as an assistant state attorney general. Sparks and Wallace remained close friends over the years, and, according to those who knew them, the former governor was “like an uncle” to his young friend.

Chauncey Sparks and Frank Dixon

In 1950, Sparks made another attempt at the governor’s office but finished far back in a large pack of candidates. His loyalty to the Democratic Party in 1948 may have hurt him in the Black Belt, where he had previously enjoyed strong support. He remained in Eufaula and devoted the rest of his life to his law practice and to following Wallace’s rise to power.

Chauncey Sparks and Frank Dixon

In 1950, Sparks made another attempt at the governor’s office but finished far back in a large pack of candidates. His loyalty to the Democratic Party in 1948 may have hurt him in the Black Belt, where he had previously enjoyed strong support. He remained in Eufaula and devoted the rest of his life to his law practice and to following Wallace’s rise to power.

Summing up his career in a 1957 interview, Sparks modestly concluded that losing the race for governor two out of three times wasn’t much of a record. Although writers could not decide if he was a “liberal conservative” or a “conservative liberal,” they all agreed that, as governor, he set aside parochial interests and most often did what he could for the people of the state. He died in Eufaula on November 6, 1968, and was buried in Fairview Cemetery.

Note: This entry was adapted with permission from Alabama Governors: A Political History of the State, edited by Samuel L. Webb and Margaret Armbrester (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001).

Further Reading

- Sparks, Chauncey. Folder. Alabama Department of Archives and History, Montgomery, Alabama.