Black Belt-Big Mule Coalition

The label Black Belt-Big Mule Coalition refers to a political coalition of businessmen and politicians who represented and promoted the interests of large‑scale agriculture and industry and dominated Alabama state politics throughout much of the twentieth century. The agricultural interests were centered in the state’s Black Belt region, where large cotton plantations dominated, but the plantation owners were also joined by timber and farm-related businesses.

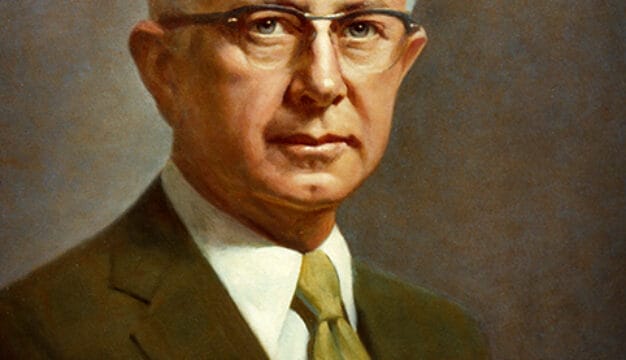

Bibb Graves, 1927

Big Mules refers to the economic elites of industrial Alabama located mainly in and around the city of Birmingham, with its iron and steel mills, coal mines, railroads, utility companies, insurance companies, law firms, and other big businesses. Other urban centers, such as Gadsden and Mobile, were also part of the Big Mule base. The term had its roots in populist politics, with Bibb Graves probably being the first to use the epithet in his successful 1926 campaign for governor. James E. “Big Jim” Folsom Sr. employed the term in repeated campaigns, often tying the Big Mules to their agricultural allies as the major barriers to economic development and political change in the state. The term is used infrequently outside Alabama.

Bibb Graves, 1927

Big Mules refers to the economic elites of industrial Alabama located mainly in and around the city of Birmingham, with its iron and steel mills, coal mines, railroads, utility companies, insurance companies, law firms, and other big businesses. Other urban centers, such as Gadsden and Mobile, were also part of the Big Mule base. The term had its roots in populist politics, with Bibb Graves probably being the first to use the epithet in his successful 1926 campaign for governor. James E. “Big Jim” Folsom Sr. employed the term in repeated campaigns, often tying the Big Mules to their agricultural allies as the major barriers to economic development and political change in the state. The term is used infrequently outside Alabama.

Big Mule industrialists needed Black Belt support because of the advantage that the Black Belt counties held in the state legislature as a result of the apportionment formula established in the 1901 Constitution. Thus the Black Belt planters controlled the legislative action that would defend the Big Mules’ economic power. By staying on good terms with the planters, Big Mules were able to ensure that Black Belt proponents would not join legislators from other rural areas to bully the urban counties and their increasing wealth.

As the population in the Black Belt decreased over time, largely as a result of African Americans relocating to Alabama cities and northern states, the populations of Birmingham, Mobile, Montgomery, and other cities grew. Even though reapportionment of the state legislature was required after each federal census, state lawmakers resisted redrawing political boundaries, and the rurally dominated legislature did not reapportion itself until federal court decisions in the 1960s ordered such action. Until that time, Jefferson County had only one state senator. The first fully reapportioned legislature did not meet until the 1970s.

John M. Patterson

The Big Mules and their agricultural allies shared a need for a compliant, low‑wage labor force, low taxes, tax exemptions, and low levels of government spending in order to maintain their social and economic power. The Black Belt‑Big Mule Coalition provided the means to achieve this and other ends. Both factions of the coalition actively recruited candidates for office and bankrolled their campaigns. In the Black Belt, planters such as J. Bruce Henderson of Wilcox County and Sam Englehardt of Macon County served in the legislature for many years. The Big Mules, on the other hand, recruited from among the management class of their corporations or looked to their law firms for likely prospects. These men were well educated, financially comfortable, and loyal to their employers. An example is Birmingham attorney Albert Boutwell, who served in the Alabama Senate and as lieutenant governor under Governor John Patterson.

John M. Patterson

The Big Mules and their agricultural allies shared a need for a compliant, low‑wage labor force, low taxes, tax exemptions, and low levels of government spending in order to maintain their social and economic power. The Black Belt‑Big Mule Coalition provided the means to achieve this and other ends. Both factions of the coalition actively recruited candidates for office and bankrolled their campaigns. In the Black Belt, planters such as J. Bruce Henderson of Wilcox County and Sam Englehardt of Macon County served in the legislature for many years. The Big Mules, on the other hand, recruited from among the management class of their corporations or looked to their law firms for likely prospects. These men were well educated, financially comfortable, and loyal to their employers. An example is Birmingham attorney Albert Boutwell, who served in the Alabama Senate and as lieutenant governor under Governor John Patterson.

Both groups in the coalition often recruited and supported candidates for local office within their counties and attempted to structure local government to their advantage. For example, the Big Mules were a major force in the movement that changed Birmingham’s city government from a commission system to a mayor‑council system. The move in part resulted from the massive negative publicity the city received when commission member and police commissioner Eugene “Bull“ Connor directed heavy force at civil rights demonstrators. This media coverage damaged business and endangered the social and economic well‑being of the city. The Big Mules recruited Boutwell to run for mayor and backed him financially; he was elected the city’s first mayor under its new mayor/council form of government in 1963.

The coalition blocked major economic and social change by constraining labor movements and disenfranchising African Americans and poor whites. It also prevented populist reforms such as railroad and utility regulation, statutory restrictions on the crop lien system, progressive taxation, quality public education, and legislative reapportionment from taking root in Alabama. In addition, the coalition used race as a wedge to forestall the state’s economic have‑nots from joining forces against the Big Mules. These goals were accomplished through statute and through constitutional amendments.

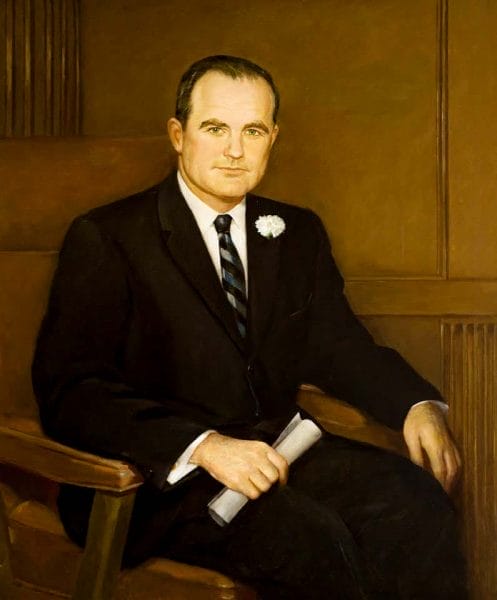

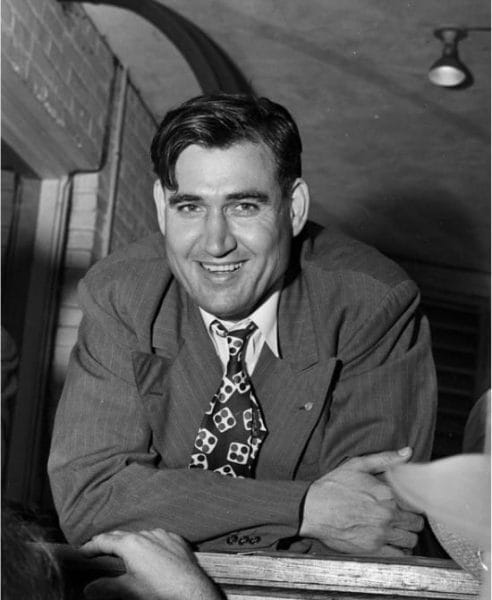

James “Big Jim” Folsom Sr.

The coalition focused its major political action on the Alabama Senate using a tactic referred to as “18 plus 1.” In the 35‑seat Senate, the coalition needed 18 seats to hold a majority and thus control the legislative agenda. In the executive branch, the governor had the ability to veto legislation, and in a tradition not broken until the late twentieth century, the lieutenant governor helped organize the Senate and select legislators to chair the various committees. Thus, control of 18 senate seats plus either the governor’s or lieutenant governor’s office meant control of state government. Members therefore funneled campaign money and other resources to races for the state senate and either the governor or lieutenant governor. Their efforts were very successful when it came to the legislative races that were local in emphasis. As the numbers of Black Belt voters declined and the population of other regions of the state, particularly north Alabama, grew, the statewide electorate became more difficult to control. The coalition was more successful in maintaining influence over the lieutenant governor position than the governorship in part because the lieutenant governor race was less visible and the candidates less known to the general public. Gubernatorial candidates, such as James E. “Big Jim” Folsom Sr., were able to get elected periodically without their support by relying on a populist campaign and their own political connections.

James “Big Jim” Folsom Sr.

The coalition focused its major political action on the Alabama Senate using a tactic referred to as “18 plus 1.” In the 35‑seat Senate, the coalition needed 18 seats to hold a majority and thus control the legislative agenda. In the executive branch, the governor had the ability to veto legislation, and in a tradition not broken until the late twentieth century, the lieutenant governor helped organize the Senate and select legislators to chair the various committees. Thus, control of 18 senate seats plus either the governor’s or lieutenant governor’s office meant control of state government. Members therefore funneled campaign money and other resources to races for the state senate and either the governor or lieutenant governor. Their efforts were very successful when it came to the legislative races that were local in emphasis. As the numbers of Black Belt voters declined and the population of other regions of the state, particularly north Alabama, grew, the statewide electorate became more difficult to control. The coalition was more successful in maintaining influence over the lieutenant governor position than the governorship in part because the lieutenant governor race was less visible and the candidates less known to the general public. Gubernatorial candidates, such as James E. “Big Jim” Folsom Sr., were able to get elected periodically without their support by relying on a populist campaign and their own political connections.

In another popular Big Mule tactic, a corporation such as the Alabama Power Company would buy the loyalties of recent law school graduates by placing them on a monthly retainer. They rarely did any work for the corporation, but its status as a client would prevent them from taking any cases against it. If any of these men had political ambitions, they would be beholden to the corporation. These retainers represented a major source of income for lawyers just establishing their practices in Alabama’s small towns and cities.

Urban‑rural differences were a strain on the relationship between the coalition’s major segments. As the nation industrialized after World War II, Alabama and its major cities did not enjoy fully the economic prosperity that occurred elsewhere because the growth in population and industry was still a threat to the state’s Black Belt planters. The civil rights movement and the negative publicity generated by violent or indifferent official responses to it further hurt economic expansion. During this period, citizens in Birmingham and other urban centers increasingly turned away from the long-standing Democratic Party, voting Republican in presidential elections and slowly changing the political dynamics within the state. These and other forces created restlessness in the urban professional and managerial classes over the limitations imposed by the controlling Black Belt‑Big Mule interests. It was not until federally mandated congressional redistricting and state legislative reapportionment, however, that the coalition was finally broken.

After the 1960 U.S. Census, Alabama lost one seat in the U.S. House of Representatives. Reapportionment supporters tied a vote for new congressional districts to limited reapportionment of the state legislature. Rural interests countered with a plan known as Chop‑Up that took away the one congressional seat held by Jefferson County and divided the county into four sections, with each section becoming part of different congressional districts. Supporters of the plan argued that it increased the county’s power base in Congress, but Jefferson County politicos viewed it as an attempt to weaken their political power. The legislation passed the House and Senate but was vetoed by Governor John Patterson. The House overrode the veto, but in a bitter fight that included one of the longest filibusters in Alabama Senate history, the redistricting plan was blocked. Legislators from some of the northern and urban counties played the greatest role in blocking Chop‑Up, and political relationships began to change.

Federal court decisions that began to be handed down in 1962 resulted in periodic reapportionment of the state legislature that increased the representation of urban areas at the expense of the Black Belt and other rural areas. New coalitions formed around specific issues, with urban interests more likely to work together to find ways to overcome constitutional restrictions in such areas as economic development, taxation, and home rule.

Additional Resources

Farmer, Hallie. The Legislative Process in Alabama. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1949.

Grafton, Carl and Anne Permaloff. Big Mules and Branchheads: James E. Folsom and Political Power in Alabama. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1985.

McMillan, Malcolm C. Constitutional Development in Alabama, 1789‑1901. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1955.

Permaloff, Anne and Carl Grafton. “The Chop‑Bill and the Big Mule Alliance.” Alabama Review 43, no. 4 (October 1990): 243‑269.

Permaloff, Anne and Carl Grafton. “Political Geography and Power Elites: Big Mules and the Alabama Constitution.” In The Constitutionalism of American States (pp. 235‑25), George Connor and Christopher Hammons, eds. Columbia, Mo.: University of Missouri Press, 2008.

Permaloff, Anne and Carl Grafton. Political Power in Alabama: The More Things Change . . . . Athens, Ga.: University of Georgia Press, 1995.