Civil War in Alabama

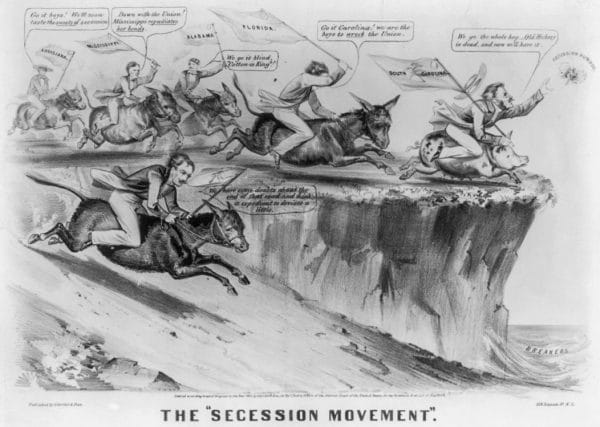

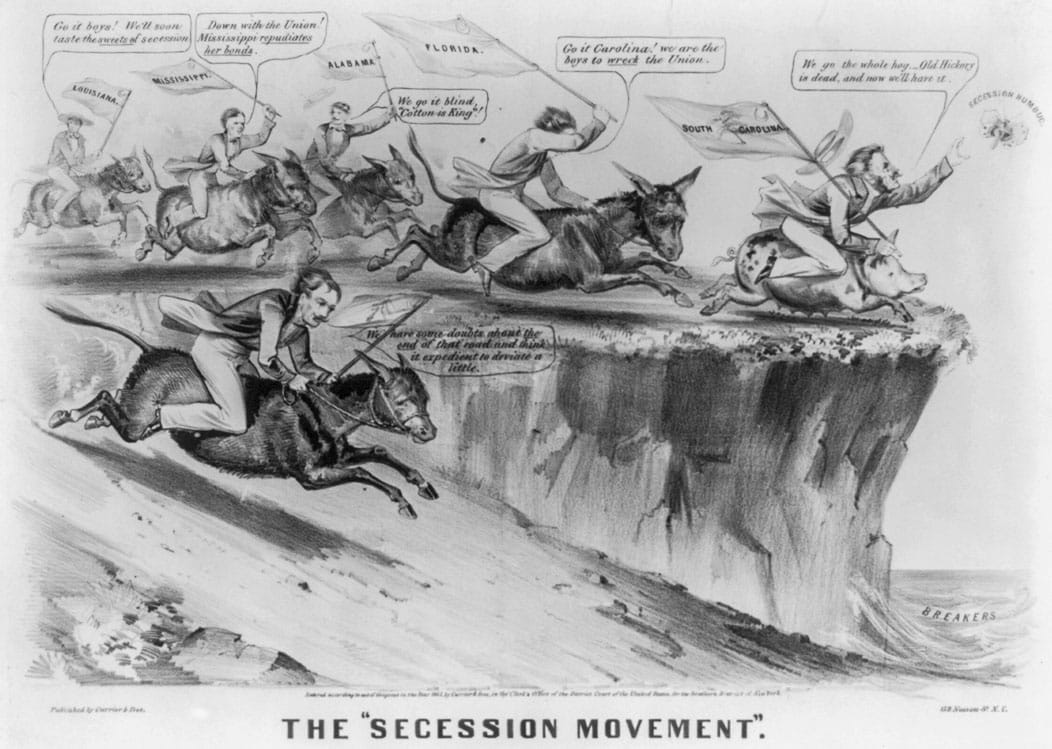

The American Civil War remains the most significant event in Alabama’s history. The war pitted Unionists, as those who remained loyal to the United States were called, against Secessionists. The war ended slavery. The war encouraged industrialization. Alabamians came to identify themselves not as Americans but as southerners, fiercely loyal to their Lost Cause. All of this was purchased with the lives of 600,000 Americans.

Tensions had been building for years when Abraham Lincoln was elected to the presidency in November 1860. Many politically powerful Alabamians viewed the election as an opening wedge that threatened to destroy slavery and begin a race war. Across the state came cries for unity in the face of this challenge. In Mobile, citizens passed a series of resolutions calling Lincoln’s election “a virtual overthrow of the Constitution and the equal rights of the States” and demanding that Alabama “withdraw from the Federal Union without any further delay.” Residents in small towns followed suit by passing their own resolutions. Gov. A. B. Moore called a December 24 election for delegates to a constitutional convention. Assembling on January 7, 1861, the delegates four days later voted to declare Alabama’s immediate independence from the United States. Guns blared and Montgomery women presented to the secession convention a flag bearing a single star, thus announcing that Alabama had withdrawn its star from the U.S. flag and was now flying it alone. Those present understood that soon Alabama would add its star to a new confederacy of states, three of which had already seceded from the United States.

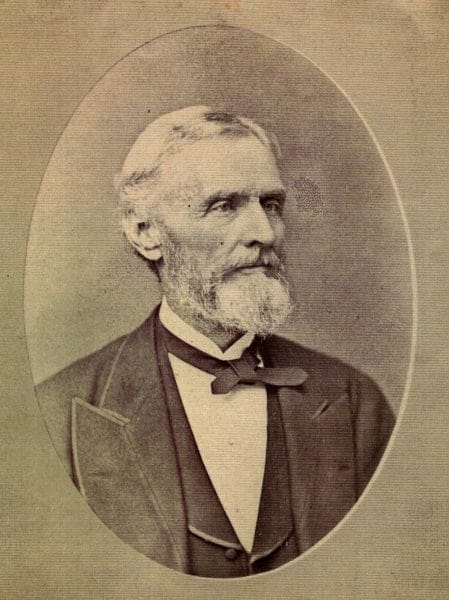

Jefferson Davis

The convention produced a vote of 61 to 39 in favor of secession, but this result cannot be taken as an easy and exact method of gauging either the citizenry’s support for, or resistance to, the Union. Some delegates certainly voted against the measure because they opposed secession altogether. Others voted against the measure because they opposed immediate withdrawal in favor of cooperation with other states. Still others voted one way or the other for personal reasons that will never be known. And, of course, these delegates were themselves elected without any votes by women or by the 45 percent of Alabamians who were enslaved. At any rate, the delegates’ less-than-unanimous vote for immediate secession was masked by loud and unceasing calls for a unified citizenry.

Jefferson Davis

The convention produced a vote of 61 to 39 in favor of secession, but this result cannot be taken as an easy and exact method of gauging either the citizenry’s support for, or resistance to, the Union. Some delegates certainly voted against the measure because they opposed secession altogether. Others voted against the measure because they opposed immediate withdrawal in favor of cooperation with other states. Still others voted one way or the other for personal reasons that will never be known. And, of course, these delegates were themselves elected without any votes by women or by the 45 percent of Alabamians who were enslaved. At any rate, the delegates’ less-than-unanimous vote for immediate secession was masked by loud and unceasing calls for a unified citizenry.

One month later, delegates from six other seceded states met in Montgomery to create the new government of the Confederate States of America. Alabama quickly offered Montgomery to serve as the new government’s capital. The new president, Jefferson Davis, arrived on February 16. He was welcomed by rabid secessionist William Lowndes Yancey. “The man and the hour have met,” Yancey proclaimed. Two days later on the statehouse portico, Davis took the oath as president of the Confederate States of America and set about to run a new American nation founded on the perpetuation of slavery, as his vice president, Alexander Stephens, explicitly stated.

In anticipation of the state’s secession, Governor Moore had months earlier ordered the state’s militiamen to seize the federal forts Morgan and Gaines at the entrance to Mobile Bay and the Mount Vernon arsenal north of Mobile. Their bloodless accomplishment on January 4 encouraged the belief that conflict with the North, if indeed there were to be a conflict, would not amount to much. Alabamians went on with their daily lives. But not all federal properties fell as easily as those in Alabama, and Confederate batteries opened fire on troops in Union-occupied Fort Sumter in Charleston harbor on April 12.

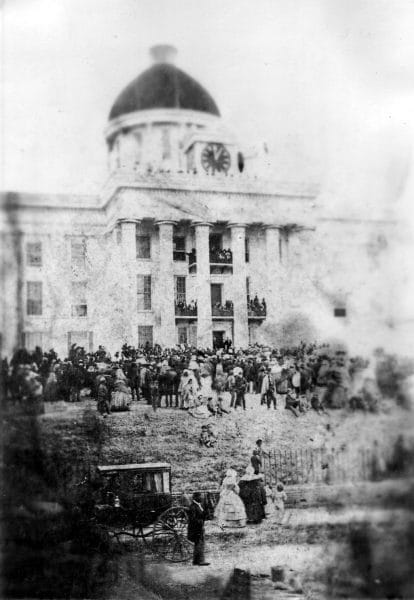

Inauguration of Jefferson Davis

Young men immediately joined existing military companies or formed new ones and began drilling. Here was an opportunity—for glory, for an adventure, for a future—that young men could not resist. Eventually more than 82,500 Alabamians would serve, but in 1861 a soldier’s greatest concern was that the war would end before he had a chance to get to the front. The companies quickly began assembling in Montgomery, where they were grouped into regiments and sent to the eastern and western battlefronts. The illusion of a short war did not last long. At the First Battle of Manassas in northern Virginia (where Gen. Barnard Bee, commanding the Fourth Alabama, would give Thomas Jackson his nickname “Stonewall”), the Confederates pursued U.S. forces back to Washington. But they did not give up. Despite a series of Confederate victories in the East that lasted into the summer of 1863, the United States continued fighting.

Inauguration of Jefferson Davis

Young men immediately joined existing military companies or formed new ones and began drilling. Here was an opportunity—for glory, for an adventure, for a future—that young men could not resist. Eventually more than 82,500 Alabamians would serve, but in 1861 a soldier’s greatest concern was that the war would end before he had a chance to get to the front. The companies quickly began assembling in Montgomery, where they were grouped into regiments and sent to the eastern and western battlefronts. The illusion of a short war did not last long. At the First Battle of Manassas in northern Virginia (where Gen. Barnard Bee, commanding the Fourth Alabama, would give Thomas Jackson his nickname “Stonewall”), the Confederates pursued U.S. forces back to Washington. But they did not give up. Despite a series of Confederate victories in the East that lasted into the summer of 1863, the United States continued fighting.

Although Alabama’s relative geographic isolation shielded it from the fiercest fighting, the Union forces did not take long to reach the state. On February 6, 1862, a mere six months after Manassas, three federal gunboats steamed up the Tennessee River to Florence. North Alabama was controlled for the most part by the Union from that time, because the river was an important route into the Confederate heartland. The railroads through north Alabama were also strategic objectives; and Huntsville, which lay along the Memphis & Charleston Railroad, was occupied two months later, on April 11.

The occupation of north Alabama remained an important objective for the U.S. military throughout the war and not merely because of its transportation routes. Many Northern politicians, and President Lincoln in particular, believed that they could undermine the Confederacy from within by courting the isolated Unionists in north Alabama and east Tennessee. They had been encouraged by the geographical distribution of votes during the 1861 convention, in which the Alabama highlands opposed secession and later sent troops to fight for the United States, most conspicuously the First Alabama Union Cavalry. But clearly Lincoln overestimated the Southern Unionists’ ability to affect the course of the war, and just as clearly Confederate politicians underestimated the extent of genuine and principled dissatisfaction with Alabama’s leaving the Union. Evaluating the motives and views of the Alabama Unionists confounded the politicians at the time and has confounded historians of our own time.

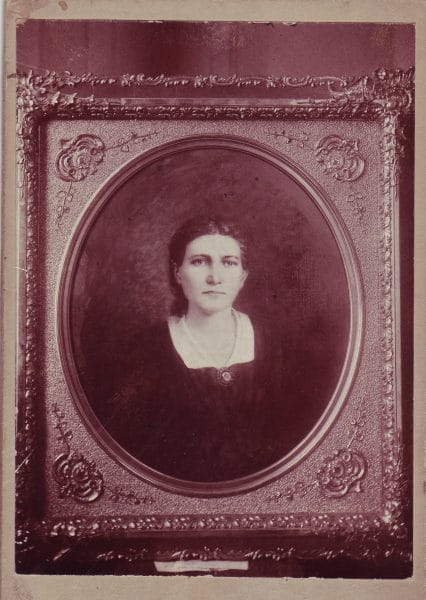

Emma Sansom

Federal strongholds in north Alabama gave Col. Abel Streight a base from which to launch his raid on the railroad between Chattanooga and Atlanta, then supplying the Army of Tennessee. His 1,700 troops, forced through lack of other options to ride on mules, left Tuscumbia in April 1863. Only four days into the raid, Confederate cavalrymen under Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest met them on Sand Mountain and began harassing the federal raiders. A local girl, Emma Sansom, led Forrest’s men across Black Creek after the raiders had burned the bridge, for which the legislature awarded her a gold medal. A few days later near Rome, Georgia, Streight’s by-then exhausted forces surrendered and were sent to Libby Prison in Richmond. Although patently unsuccessful, this would not be the last raid into Alabama.

Emma Sansom

Federal strongholds in north Alabama gave Col. Abel Streight a base from which to launch his raid on the railroad between Chattanooga and Atlanta, then supplying the Army of Tennessee. His 1,700 troops, forced through lack of other options to ride on mules, left Tuscumbia in April 1863. Only four days into the raid, Confederate cavalrymen under Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest met them on Sand Mountain and began harassing the federal raiders. A local girl, Emma Sansom, led Forrest’s men across Black Creek after the raiders had burned the bridge, for which the legislature awarded her a gold medal. A few days later near Rome, Georgia, Streight’s by-then exhausted forces surrendered and were sent to Libby Prison in Richmond. Although patently unsuccessful, this would not be the last raid into Alabama.

In August 1864, U.S. Navy admiral David Farragut assembled a fleet of ironclads and wooden-hulled frigates to take Mobile Bay. According to legend, Farragut issued the famous rallying cry, “Damn the torpedoes. Full speed ahead,” and guided his ships past the heavily fortified entrance to Mobile Bay. Two weeks later, after sieges of forts Gaines and Morgan, federal forces controlled the bay. Because the city of Mobile remained in Confederate hands until the end of the war, the victory was as much psychological as it was tactical.

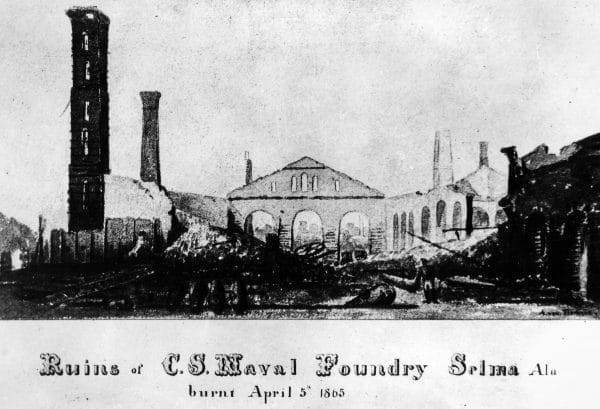

Selma Naval Foundry

Part of the U.S. strategy—squeezing Alabama from the north and south—was to destroy Alabama’s ability to feed the armies and arm the Confederate war machine. During the 1850s, a number of Alabama entrepreneurs had tried to develop an industrial infrastructure centering on railroads and iron-making. These early industries did not fare well for several reasons, chief among them that it was simply too easy to make money growing cotton. The start of the war found Alabama, indeed the Confederacy, nearly devoid of weapons. The state procured some by seizing the Mount Vernon arsenal and by purchasing others. But as the war dragged on and the federal blockade became increasingly effective, it was evident that the South would have to arm itself. The individual largely responsible for this was Josiah Gorgas, chief of ordnance for the Confederacy. He began by melting down domestic civilian goods and by 1863 had created an industrial corridor through central Alabama of iron furnaces, rolling mills, powder mills, arsenals, laboratories, and factories. Arguably his most impressive achievement was the Selma foundry and manufacturing complex, employing 3,000 men and producing more than 100 of the famous and technologically advanced Brooke rifled cannon. In the ensuing decades and in civilian hands, industry would transform Alabama.

Selma Naval Foundry

Part of the U.S. strategy—squeezing Alabama from the north and south—was to destroy Alabama’s ability to feed the armies and arm the Confederate war machine. During the 1850s, a number of Alabama entrepreneurs had tried to develop an industrial infrastructure centering on railroads and iron-making. These early industries did not fare well for several reasons, chief among them that it was simply too easy to make money growing cotton. The start of the war found Alabama, indeed the Confederacy, nearly devoid of weapons. The state procured some by seizing the Mount Vernon arsenal and by purchasing others. But as the war dragged on and the federal blockade became increasingly effective, it was evident that the South would have to arm itself. The individual largely responsible for this was Josiah Gorgas, chief of ordnance for the Confederacy. He began by melting down domestic civilian goods and by 1863 had created an industrial corridor through central Alabama of iron furnaces, rolling mills, powder mills, arsenals, laboratories, and factories. Arguably his most impressive achievement was the Selma foundry and manufacturing complex, employing 3,000 men and producing more than 100 of the famous and technologically advanced Brooke rifled cannon. In the ensuing decades and in civilian hands, industry would transform Alabama.

Some of the spectacular changes wrought by the war came on, and under, the sea. Southerners had no experience in shipbuilding and were not renowned as seamen; nonetheless, they astonished their critics. The Selma works built ironclads, including the formidable CSS Tennessee, which was captured during the Battle of Mobile Bay and later placed into service by the U.S. Navy, and iron plating produced at the foundry outfitted the CSS Nashville. The first submarine to sink a ship, the H. L. Hunley, was built in Mobile. Of greater impact on the war was the raider CSS Alabama, built in Liverpool and commanded by Mobilian Raphael Semmes.

Such figures as Semmes and Gorgas were but a few of the many Alabamians who would achieve great fame during the war’s course. Robert Emmett Rodes started as captain of the Warrior Guards, Fifth Alabama Regiment, and rose to become one of Gen. Robert E. Lee’s greatest commanders. John Pelham, who turned light artillery into a mobile and unconventional weapon, earned his nickname “The Gallant Pelham” for his “unflinching courage,” in the words of General Lee. “Fighting Joe” Wheeler became one of the great cavalrymen and, as major general, commanded one of the few forces able to slow William Tecumseh Sherman in his “March to the Sea.”

James H. Wilson

Throughout the war, Alabama escaped much of the terrible destruction that other Confederate states endured. The only significant wide-scale damage was caused by U.S. Army general James H. Wilson, who launched a raid from Lauderdale County that destroyed the University of Alabama, iron furnaces in Jefferson and Bibb Counties, and the Selma industrial complex. Montgomery surrendered on April 12, the same day as Mobile and three days after Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Court House in Virginia.

James H. Wilson

Throughout the war, Alabama escaped much of the terrible destruction that other Confederate states endured. The only significant wide-scale damage was caused by U.S. Army general James H. Wilson, who launched a raid from Lauderdale County that destroyed the University of Alabama, iron furnaces in Jefferson and Bibb Counties, and the Selma industrial complex. Montgomery surrendered on April 12, the same day as Mobile and three days after Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Court House in Virginia.

Although Confederate Alabamians surrendered their weapons, they did not surrender their convictions. The conflict had led many Alabamians to identify themselves as southerners, rather than Americans. Its Confederate heroes—whether the famous Raphael Semmes, Emma Sansom, and R. E. Rodes, or the anonymous men who fell in battle—had defended what became a romanticized southern way of life. And the sacrifices of those at the battlefront, as well as those left behind on the homefront, had encumbered mutual obligations—obligations that would find expression in Confederate Memorial Day and a type of reactionary politics that, after a decade of maneuvering, would dominate the state for another century.

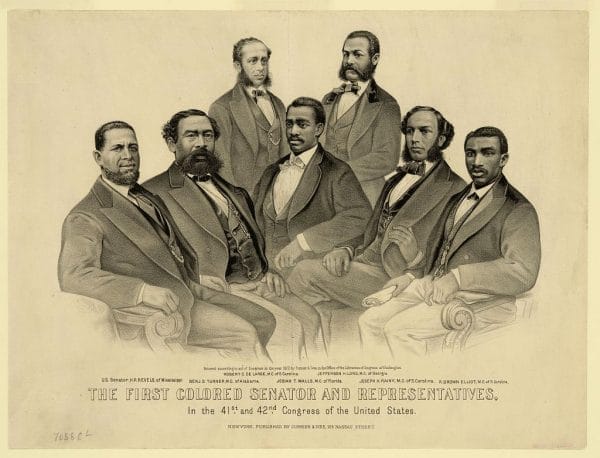

Black Legislators Elected During Reconstruction

The war created defiance among many Alabamians, who remained hidebound to their past, but the war also served as a defining moment for many other Alabamians. Secession identified white Unionists as dissenters. Most significantly, of course, the war freed and made citizens of the nearly 440,000 black Alabamians born into slavery. They would come to have their own heroes and their own holidays. Together, white Unionists and black freedmen likely could have formed a political majority against the former Confederates. But it was not to be. Immediately after secession, the call had been for unity. The war ended not with unity, but division; not with cooperation, but with domination—and all with the veneer of peace and tranquility. In short, the war changed everything. It created widows and orphans, heroes, a new economy, reactionary politics, and new identities. And yet for many Alabamians the war changed little, for although the war ended the legal institution of slavery, it also cemented the convictions of those who had fought to uphold that institution.

Black Legislators Elected During Reconstruction

The war created defiance among many Alabamians, who remained hidebound to their past, but the war also served as a defining moment for many other Alabamians. Secession identified white Unionists as dissenters. Most significantly, of course, the war freed and made citizens of the nearly 440,000 black Alabamians born into slavery. They would come to have their own heroes and their own holidays. Together, white Unionists and black freedmen likely could have formed a political majority against the former Confederates. But it was not to be. Immediately after secession, the call had been for unity. The war ended not with unity, but division; not with cooperation, but with domination—and all with the veneer of peace and tranquility. In short, the war changed everything. It created widows and orphans, heroes, a new economy, reactionary politics, and new identities. And yet for many Alabamians the war changed little, for although the war ended the legal institution of slavery, it also cemented the convictions of those who had fought to uphold that institution.

Further Reading

- Center, Clark E., Jr. “The Burning of the University of Alabama.” Alabama Heritage 16 (Spring 1990): 30-45.

- Dodd, Donald B. “The Free State of Winston.” Alabama Heritage 28 (Spring 1993): 9-19.

- Heinze, Christopher M. “The Saga of C.S.S. Alabama.” Alabama Heritage 37 (Summer 1995): 6-23.

- Hubbs, G. Ward. Guarding Greensboro: A Confederate Company in the Making of a Southern Community. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2003.

- Jones, James Pickett. Yankee Blitzkrieg: Wilson’s Raid through Alabama and Georgia. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1987.

- McIlwain, Christopher Lyle, Sr. Civil War Alabama. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2016.

- McMillan, Malcolm Cook. The Alabama Confederate Reader. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1963.

- Noe, Kenneth W., ed. The Yellowhammer War: The Civil War and Reconstruction in Alabama. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2013.

- Rogers, William Warren. Confederate Home Front: Montgomery During the Civil War. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1999.