Martin Luther King Jr.

Civil Rights Leaders in Selma

Minister, philosopher, and social activist Martin Luther King Jr. (1929-1968) was America’s most significant civil rights leader of the 1950s and 1960s. He achieved his most renown and greatest successes in advancing the cause of civil rights while leading a series of highly publicized campaigns in Alabama between 1955 and 1965. During this decade of mass protests against racial injustices, King’s words and deeds inspired millions of people throughout the world. In 1964, he won the Nobel Peace Prize for his leadership in the struggle for racial equality. In contrast, others saw King as a polarizing figure whose actions elicited violent reactions. He was assassinated on April 4, 1968. Fifteen years later, in November 1983, President Ronald Reagan signed a bill establishing the third Monday of every January as the Martin Luther King Jr. National Holiday.

Civil Rights Leaders in Selma

Minister, philosopher, and social activist Martin Luther King Jr. (1929-1968) was America’s most significant civil rights leader of the 1950s and 1960s. He achieved his most renown and greatest successes in advancing the cause of civil rights while leading a series of highly publicized campaigns in Alabama between 1955 and 1965. During this decade of mass protests against racial injustices, King’s words and deeds inspired millions of people throughout the world. In 1964, he won the Nobel Peace Prize for his leadership in the struggle for racial equality. In contrast, others saw King as a polarizing figure whose actions elicited violent reactions. He was assassinated on April 4, 1968. Fifteen years later, in November 1983, President Ronald Reagan signed a bill establishing the third Monday of every January as the Martin Luther King Jr. National Holiday.

Early Life and Career

Martin Luther and Coretta Scott King

Originally named Michael Luther, King was born on January 15, 1929, in Atlanta, Georgia, to Reverend Michael Luther and Alberta Williams King. Following a trip to Europe in 1934, King Sr. changed both his name and that of his son to Martin Luther to honor the leader of the Protestant Reformation. The younger King had one sister, Christine, and a brother, Alfred Daniel (A.D.)—the latter spent several years as a pastor at a Baptist church in western Birmingham. As the son of a minister, King’s early life was centered on activities at the prestigious Ebenezer Baptist Church, where he sang in the choir. King left grade school at 15 and entered Morehouse College, intending to follow his father into the ministry. That same year he preached his first sermon at Ebenezer. He graduated from Morehouse in 1948 with a bachelor’s degree in sociology and began theological studies at Crozer Seminary in Chester, Pennsylvania. In 1951, King began course work for a doctorate at Boston University, where he studied various aspects of liberal Protestant theology and wrote a dissertation comparing the ideas of theologians Paul Tillich and Henry Nelson Wieman. While there, he met Coretta Scott, a young woman from Perry County, Alabama, who was studying voice at Boston’s New England Conservatory of Music. King’s father initially objected to his son’s romance with a “country girl” from Alabama but nonetheless performed the couple’s wedding ceremony on June 18, 1953, on the Scott family farm in Heiberger, just north of Marion. The couple would have four children: Yolanda Denise, Martin Luther III, Dexter Scott, and Bernice Albertine.

Martin Luther and Coretta Scott King

Originally named Michael Luther, King was born on January 15, 1929, in Atlanta, Georgia, to Reverend Michael Luther and Alberta Williams King. Following a trip to Europe in 1934, King Sr. changed both his name and that of his son to Martin Luther to honor the leader of the Protestant Reformation. The younger King had one sister, Christine, and a brother, Alfred Daniel (A.D.)—the latter spent several years as a pastor at a Baptist church in western Birmingham. As the son of a minister, King’s early life was centered on activities at the prestigious Ebenezer Baptist Church, where he sang in the choir. King left grade school at 15 and entered Morehouse College, intending to follow his father into the ministry. That same year he preached his first sermon at Ebenezer. He graduated from Morehouse in 1948 with a bachelor’s degree in sociology and began theological studies at Crozer Seminary in Chester, Pennsylvania. In 1951, King began course work for a doctorate at Boston University, where he studied various aspects of liberal Protestant theology and wrote a dissertation comparing the ideas of theologians Paul Tillich and Henry Nelson Wieman. While there, he met Coretta Scott, a young woman from Perry County, Alabama, who was studying voice at Boston’s New England Conservatory of Music. King’s father initially objected to his son’s romance with a “country girl” from Alabama but nonetheless performed the couple’s wedding ceremony on June 18, 1953, on the Scott family farm in Heiberger, just north of Marion. The couple would have four children: Yolanda Denise, Martin Luther III, Dexter Scott, and Bernice Albertine.

Influences on King

King drew from a variety of traditions, philosophers, theologians, and moralists in formulating his ideas on race, justice, and civil rights. Like many black preachers before him, King used his ministerial status to protest injustices, inspire his followers to become faith-based community activists, and tap into monetary sources within the black church. King rejected some of the religious views of the traditional black church, however. He embraced the notion that a preacher must minister to the external and physical needs of an individual in addition to internal and spiritual needs. He found inspiration in the writings of American theologian Reinhold Niebuhr and essayist Henry David Thoreau, who both helped him develop his views that an individual should refuse to cooperate with an evil system and had the right to disobey unfair laws. In the actions of Indian political and spiritual leader Mahatma Gandhi, he found support for his belief in nonviolent resistance to injustice and the use of love to resist evil. These influences and others helped King develop a strategy of protest and civil disobedience using love and nonviolent tactics to confront the racist laws and customs of the American South, which he viewed as an evil, unjust system created by immoral men.

King Moves to Montgomery

Dexter Avenue Baptist Church

In 1954 Martin Luther King Jr. applied for a job as the new pastor at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, located near the Alabama state capital building in Montgomery. While there to preach a trial sermon to the congregation, King befriended the pastor of First Baptist Church, Alabamian Ralph Abernathy, another future leader of the civil rights movement. Although King had other job opportunities, the prospect of making a name for himself as a minister beyond the shadow of his father, combined with Dexter Avenue’s elite status in Montgomery’s African American community, enticed the 25-year-old preacher to accept the position. By 1955, King was known in Montgomery and around the region as a commanding orator with a passionate but measured delivery. That same year, the young preacher completed his doctoral dissertation, “A Comparison of the Conception of God in the Thinking of Paul Tillich and Henry Nelson Wieman.” Some 30 years later, however, scholars discovered that King had plagiarized parts of this study, dozens of other academic papers, and subsequent writings and sermons.

Dexter Avenue Baptist Church

In 1954 Martin Luther King Jr. applied for a job as the new pastor at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, located near the Alabama state capital building in Montgomery. While there to preach a trial sermon to the congregation, King befriended the pastor of First Baptist Church, Alabamian Ralph Abernathy, another future leader of the civil rights movement. Although King had other job opportunities, the prospect of making a name for himself as a minister beyond the shadow of his father, combined with Dexter Avenue’s elite status in Montgomery’s African American community, enticed the 25-year-old preacher to accept the position. By 1955, King was known in Montgomery and around the region as a commanding orator with a passionate but measured delivery. That same year, the young preacher completed his doctoral dissertation, “A Comparison of the Conception of God in the Thinking of Paul Tillich and Henry Nelson Wieman.” Some 30 years later, however, scholars discovered that King had plagiarized parts of this study, dozens of other academic papers, and subsequent writings and sermons.

Fred Gray

King’s rise to national prominence began with events in 1955. On December 1, 1955, Montgomery police officers arrested Rosa Parks for refusing to give her bus seat to a white man. Community activists elected King as president of the Montgomery Improvement Association, a group created to organize protests and a boycott of city buses, most likely because he was relatively new to the city and had no problematic allegiances to the various factions within the black community. The boycott, which lasted more than a year, ended in December 1956, when the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed a lower court’s ruling that Alabama’s laws requiring segregation on buses were unconstitutional. King, Abernathy, Parks, her attorney Fred Gray, and others were among the first to ride on Montgomery’s integrated buses.

Fred Gray

King’s rise to national prominence began with events in 1955. On December 1, 1955, Montgomery police officers arrested Rosa Parks for refusing to give her bus seat to a white man. Community activists elected King as president of the Montgomery Improvement Association, a group created to organize protests and a boycott of city buses, most likely because he was relatively new to the city and had no problematic allegiances to the various factions within the black community. The boycott, which lasted more than a year, ended in December 1956, when the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed a lower court’s ruling that Alabama’s laws requiring segregation on buses were unconstitutional. King, Abernathy, Parks, her attorney Fred Gray, and others were among the first to ride on Montgomery’s integrated buses.

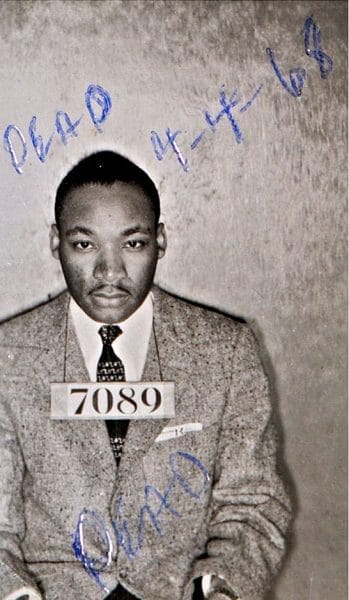

Martin Luther King Jr. Booking Photo

Despite its importance, the Montgomery bus boycott failed to spark a wider effort to end racial segregation and voting discrimination in Alabama and the rest of the South. The subsequent 1957 Civil Rights Act—which strengthened existing civil and voting rights laws, established a federal civil rights commission, and created the position of assistant U.S. attorney general for civil rights—was the first national civil rights legislation since Reconstruction. For King, the law fell short of his broader vision of ending racial segregation and voting discrimination. Nonetheless, the bus boycott did establish King as a leader in the civil rights movement in Alabama. In his sermons, King interpreted the situation with clear and direct language and learned how to use the media to show the nation the realities of segregation. After the boycott, King became more than just the pastor of Dexter Avenue Baptist or simply the leader of a city-wide movement—he had become part of American popular culture.

Martin Luther King Jr. Booking Photo

Despite its importance, the Montgomery bus boycott failed to spark a wider effort to end racial segregation and voting discrimination in Alabama and the rest of the South. The subsequent 1957 Civil Rights Act—which strengthened existing civil and voting rights laws, established a federal civil rights commission, and created the position of assistant U.S. attorney general for civil rights—was the first national civil rights legislation since Reconstruction. For King, the law fell short of his broader vision of ending racial segregation and voting discrimination. Nonetheless, the bus boycott did establish King as a leader in the civil rights movement in Alabama. In his sermons, King interpreted the situation with clear and direct language and learned how to use the media to show the nation the realities of segregation. After the boycott, King became more than just the pastor of Dexter Avenue Baptist or simply the leader of a city-wide movement—he had become part of American popular culture.

From Montgomery to Birmingham

In early 1957, King, Abernathy, Birmingham native Fred Shuttlesworth, and other black ministers from Alabama and throughout the South met in Atlanta and created the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) to help coordinate further mass protests. Initially, however, the group struggled to find a focus. The SCLC was poorly funded, and its leaders were deeply divided on how to continue the fight for racial equality. Prior to the presidential election of 1960, the group launched a voting rights campaign, but it had little significant impact. Other ideas for confronting racial injustices, including leadership training and citizenship education, were never implemented. King decided to return to Atlanta and serve as co-pastor at Ebenezer Baptist Church with his father. The move provided him with a broader support network and freed him from the demands of being the sole pastor at Dexter Avenue.

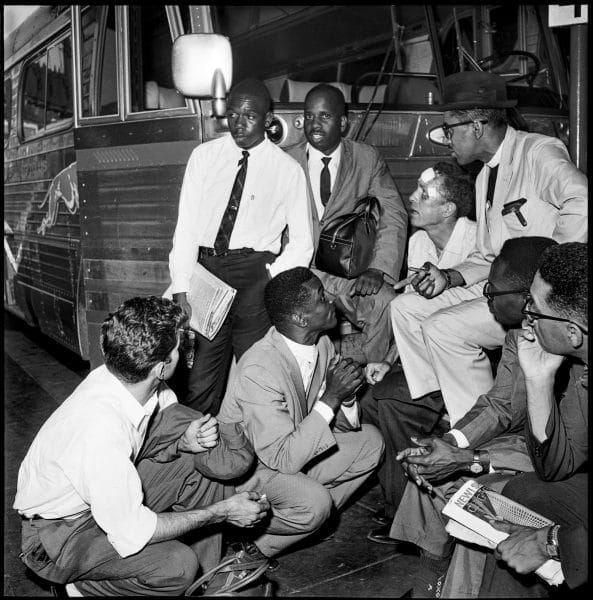

Fred Shuttlesworth and Freedom Riders

In February 1960, students in Greensboro, North Carolina, began a sit-in movement to protest segregated lunch counters that quickly spread throughout the South. King, who at first hesitated to join the protest in Atlanta, ultimately changed his mind amidst criticism and led a sit-in at an Atlanta department store in October and was arrested. The following year, college students who belonged to the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), including Alabamian John Lewis, commenced the Freedom Rides to test rulings desegregating public buses. King refused to participate in the protest and became alienated from some of the students. The vanguard of the fight against injustice in the South shifted from King and the SCLC to college students and their new organization, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). King realized that if he was to remain relevant to the cause, he needed to capitalize on the student’s energy and lead another mass protest. King’s decision to hire Reverend Wyatt Tee Walker as the organization’s executive director played a pivotal role in reinvigorating King and the SCLC. Walker, a taskmaster with a keen sense of public relations, brought order, focus, and discipline to the organization and began working toward returning King to the national spotlight.

Fred Shuttlesworth and Freedom Riders

In February 1960, students in Greensboro, North Carolina, began a sit-in movement to protest segregated lunch counters that quickly spread throughout the South. King, who at first hesitated to join the protest in Atlanta, ultimately changed his mind amidst criticism and led a sit-in at an Atlanta department store in October and was arrested. The following year, college students who belonged to the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), including Alabamian John Lewis, commenced the Freedom Rides to test rulings desegregating public buses. King refused to participate in the protest and became alienated from some of the students. The vanguard of the fight against injustice in the South shifted from King and the SCLC to college students and their new organization, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). King realized that if he was to remain relevant to the cause, he needed to capitalize on the student’s energy and lead another mass protest. King’s decision to hire Reverend Wyatt Tee Walker as the organization’s executive director played a pivotal role in reinvigorating King and the SCLC. Walker, a taskmaster with a keen sense of public relations, brought order, focus, and discipline to the organization and began working toward returning King to the national spotlight.

Success in the fight against segregation, however, came slowly. King and Walker’s first effort at a mass movement to confront segregation failed to attract press attention and federal intervention. The 1962 Albany, Georgia, demonstrations drained the SCLC of resources, damaged King’s reputation, and called into question the use of nonviolence as a tactic to confront segregation. The organization and the civil rights leader were in desperate need of a victory.

Birmingham

Good Friday March

Fred Shuttlesworth had the solution to this dilemma. In January 1963, Shuttlesworth invited King and the SCLC to Birmingham to work with local people already engaged in the struggle against racial inequality. On April 3, 1963, the campaign began with little fanfare, one day after Birmingham voters, both black and white, had ousted hard-line segregationist city commissioners Eugene “Bull” Connor, Arthur Hanes Sr., and James “Jabo” Waggoner. The men refused to accept the results of the April election and remained in office. During the rest of the month, however, local and national journalists, politicians, and preachers criticized the timing of the demonstrations, believing that the election results indicated the city’s willingness to move toward a more moderate government. Sit-ins, marches, and voter registration drives did little to expose the pervasive segregation in the city, as King had hoped. Birmingham police officers arrested King on Good Friday, April 12, for violating a court injunction prohibiting street demonstration without a permit. During his eight-day incarceration he began composing his “Letter from Birmingham Jail” in response to a public statement by Alabama’s leading white clergy calling for an end to the demonstrations. Subsequently, King was tried and convicted of breaking the law. On appeal, the case landed in the U.S. Supreme Court, where in the 1967 Walker v. Birmingham decision, the court upheld King’s conviction and the civil rights leader returned to Alabama to serve his jail sentence.

Good Friday March

Fred Shuttlesworth had the solution to this dilemma. In January 1963, Shuttlesworth invited King and the SCLC to Birmingham to work with local people already engaged in the struggle against racial inequality. On April 3, 1963, the campaign began with little fanfare, one day after Birmingham voters, both black and white, had ousted hard-line segregationist city commissioners Eugene “Bull” Connor, Arthur Hanes Sr., and James “Jabo” Waggoner. The men refused to accept the results of the April election and remained in office. During the rest of the month, however, local and national journalists, politicians, and preachers criticized the timing of the demonstrations, believing that the election results indicated the city’s willingness to move toward a more moderate government. Sit-ins, marches, and voter registration drives did little to expose the pervasive segregation in the city, as King had hoped. Birmingham police officers arrested King on Good Friday, April 12, for violating a court injunction prohibiting street demonstration without a permit. During his eight-day incarceration he began composing his “Letter from Birmingham Jail” in response to a public statement by Alabama’s leading white clergy calling for an end to the demonstrations. Subsequently, King was tried and convicted of breaking the law. On appeal, the case landed in the U.S. Supreme Court, where in the 1967 Walker v. Birmingham decision, the court upheld King’s conviction and the civil rights leader returned to Alabama to serve his jail sentence.

As May approached, the movement seemed on the verge of failing, as it had in Albany. James Bevel, an SCLC associate, convinced King to call out school children to fight segregation, overwhelm the police force, and fill the jails. During this controversial children’s phase of the protest movement, a political vacuum existed in the city as two governments operated simultaneously, leading one local writer to proclaim that Birmingham has two mayors, a king, and a parade every day. During the first 10 days of May, images of police dogs and fire hoses being used on protesters were shown by media outlets around the world and gave King his greatest public triumph. He later recalled that those images from Birmingham moved the nation more than anything else. Later that year, on August 28, King delivered his powerful “I Have a Dream” speech at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. In the spring of 1964, King returned to Alabama to help organize desegregation protests in Tuscaloosa, kicking off the Tuscaloosa Campaign on March 8 at the city’s First African Baptist Church. Two months later, on June 9, Tuscaloosa’s Black citizens were attacked with teargas, beatings, and fire hoses as they gathered at the church for a march, on what became known as Bloody Tuesday. On July 2, Pres. Lyndon Johnson signed into law the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which outlawed segregation in public places, and in December of that year, King won the Nobel Peace Prize.

Birmingham to Selma

In Birmingham, however, meaningful change came slowly. The process of desegregation and black political empowerment took several more years to accomplish. The slow changes frustrated King who frequently threatened to restart the Birmingham protests if the city continued to delay. Only once, in January 1966, did the protests start again, but without King and with no success. Nonetheless, the civil rights leader returned to Alabama frequently to preach in black pulpits in Birmingham, Montgomery, Bessemer, Marion, Camden, and other smaller communities throughout the state. In September 1963, he delivered his powerful “Eulogy for Martyred Children” at the joint funeral of three of the four little girls killed in the September 15 bombing of Birmingham’s Sixteenth Street Baptist Church.

Martin Luther and Coretta Scott King

In spite of constitutional guarantees, southern white politicians, especially in counties where blacks were a majority of the population, continued to deny blacks the right to vote. In January 1965, King and the SCLC joined the voting-rights campaign in Selma in which the Dallas County Voters League and SNCC volunteers were actively involved in registering black voters. On February 1, police arrested King, Abernathy, and several hundred other protestors who marched for voting rights. Following the shooting death of Jimmie Lee Jackson by an Alabama state trooper in neighboring Perry County, King and civil rights workers began organizing a march from Selma to Montgomery to press for voting rights and to protest the state government’s continued unjust treatment of blacks. The first attempt failed, ending in the infamous “Bloody Sunday” incident in which Alabama state troopers and Selma police on horseback used clubs and tear gas to turn back the marchers on the Edmund Pettus Bridge on U.S. Highway 80. The second attempt, on March 9, became known as “Turnaround Tuesday,” because King had made a secret agreement with representatives of Pres. Lyndon Johnson to stop short of crossing the bridge. The marchers said a prayer at the base of the bridge and then retreated. On March 21, 1965, the third march proceeded under the protection of federalized National Guard troops. Four days later on March 25, the marchers completed the journey, and near the state capital building in Montgomery King delivered his “Our God is Marching On” speech, best remembered for King’s repetitive phrase: “How long? Not long.” The Selma campaign marked the end of the protest era that began 10 years before in Montgomery. The subsequent Voting Rights Act of 1965 guaranteed blacks the right to vote and helped transform the electoral landscape in Alabama and throughout the South and the nation.

Martin Luther and Coretta Scott King

In spite of constitutional guarantees, southern white politicians, especially in counties where blacks were a majority of the population, continued to deny blacks the right to vote. In January 1965, King and the SCLC joined the voting-rights campaign in Selma in which the Dallas County Voters League and SNCC volunteers were actively involved in registering black voters. On February 1, police arrested King, Abernathy, and several hundred other protestors who marched for voting rights. Following the shooting death of Jimmie Lee Jackson by an Alabama state trooper in neighboring Perry County, King and civil rights workers began organizing a march from Selma to Montgomery to press for voting rights and to protest the state government’s continued unjust treatment of blacks. The first attempt failed, ending in the infamous “Bloody Sunday” incident in which Alabama state troopers and Selma police on horseback used clubs and tear gas to turn back the marchers on the Edmund Pettus Bridge on U.S. Highway 80. The second attempt, on March 9, became known as “Turnaround Tuesday,” because King had made a secret agreement with representatives of Pres. Lyndon Johnson to stop short of crossing the bridge. The marchers said a prayer at the base of the bridge and then retreated. On March 21, 1965, the third march proceeded under the protection of federalized National Guard troops. Four days later on March 25, the marchers completed the journey, and near the state capital building in Montgomery King delivered his “Our God is Marching On” speech, best remembered for King’s repetitive phrase: “How long? Not long.” The Selma campaign marked the end of the protest era that began 10 years before in Montgomery. The subsequent Voting Rights Act of 1965 guaranteed blacks the right to vote and helped transform the electoral landscape in Alabama and throughout the South and the nation.

Final Years

During the final three years of Martin Luther King’s life, he turned his attention to broader economic issues. King recruited ministers and workers from throughout Alabama and the rest of the nation to help lead what he called the Poor People’s Campaign at the local level. As the civil rights leader travelled in the state speaking to potential supporters, a habitual criminal and escaped convict, James Earl Ray, stalked him in several locations. In Birmingham, Ray purchased a Remington Game Master Model 760 rifle and took it with him to Memphis, Tennessee, where he murdered Martin Luther King on April 4, 1968. On April 9, King was buried in Atlanta near the Ebenezer Baptist Church. In the years following his death, King’s widow Coretta established the Atlanta-based Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change to help provide educational opportunities for those seeking training in the philosophy and tactics of nonviolence.

Throughout Alabama, the legacy of Martin Luther King endures on the numerous streets, highways, schools, and memorials named in his honor. King’s birthday is a national holiday, and each January his life and work are celebrated and remembered by individuals, organizations, and churches.

Further Reading

- Bass, S. Jonathan. Blessed Are the Peacemakers: Martin Luther King, Jr., Eight White Religious Leaders, and the “Letter from Birmingham Jail”. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2007.

- Branch, Taylor. Parting the Waters: America in the King Years, 1954-1963. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1988.

- ———. Pillar of Fire: America in the King Years, 1963-65. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1998.

- Eskew, Glenn. But for Birmingham: The Local and National Movements in the Civil Rights Struggle. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998.

- Thornton, Mills. Dividing Lines: Municipal Politics and the Struggle for Civil Rights in Montgomery, Birmingham, and Selma. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2002.