James E. "Big Jim" Folsom Sr. (1947-51, 1955-59)

James “Big Jim” Folsom Sr.

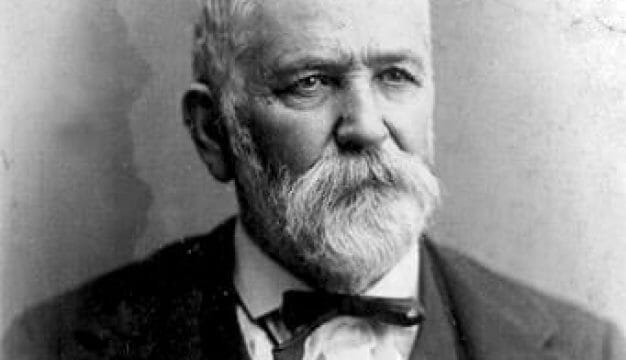

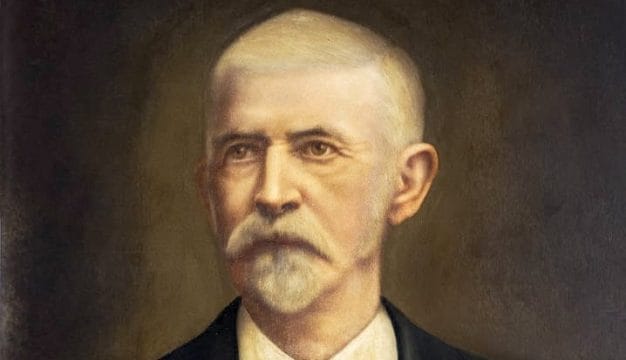

James E. “Big Jim” Folsom, Sr. (1908-1987) was only the second person to serve two full terms as governor of Alabama, from 1947 to 1951 and from 1955 to 1959. A populist, his election and his legislative agenda represented a major threat to the establishment forces that dominated Alabama government and politics. Utilizing campaign techniques pioneered by other populists with whom he identified such as Huey Long of Louisiana and Pappy Lee O’Daniel of Texas, Folsom went directly to the people, entertaining them with humor and country music and educating them about their rights and what he believed government should do for them. He advocated reapportionment of the state legislature based on population, voting rights for African Americans, an end to the convict-labor system, better public schools, farm to market roads, pensions, and other populist reforms. His effectiveness was limited by a combination of all-out attacks from the establishment, personal excesses, and corruption scandals surrounding his two administrations combined with the political forces unleashed by the Brown v. Board of Education decision.

James “Big Jim” Folsom Sr.

James E. “Big Jim” Folsom, Sr. (1908-1987) was only the second person to serve two full terms as governor of Alabama, from 1947 to 1951 and from 1955 to 1959. A populist, his election and his legislative agenda represented a major threat to the establishment forces that dominated Alabama government and politics. Utilizing campaign techniques pioneered by other populists with whom he identified such as Huey Long of Louisiana and Pappy Lee O’Daniel of Texas, Folsom went directly to the people, entertaining them with humor and country music and educating them about their rights and what he believed government should do for them. He advocated reapportionment of the state legislature based on population, voting rights for African Americans, an end to the convict-labor system, better public schools, farm to market roads, pensions, and other populist reforms. His effectiveness was limited by a combination of all-out attacks from the establishment, personal excesses, and corruption scandals surrounding his two administrations combined with the political forces unleashed by the Brown v. Board of Education decision.

James Elisha Folsom was born on October 9, 1908, near Elba, in Coffee County. He was the youngest child of the former Eulala Cornelia Dunnavant and Joshua Marion Folsom, a well-known county politician. Jim learned a love of electoral politics from his father, with whom he travelled throughout the county as a child. When Joshua Folsom died in 1919, John Dunnavant, Eulala Folsom’s brother, became Jim Folsom’s father figure. An activist in the Populist Party, Dunnavant was an effective storyteller whose politically motivated tales molded Jim Folsom’s strongly held political beliefs.

Folsom briefly attended the University of Alabama and Howard College (now Samford University), emphasizing history and government in his course selection. He left school in 1929 to assist the relief effort when the Pea River flooded Elba and then began months of drifting as a merchant sailor, boxing sparring partner, and doorman at a New York theater. He later maintained that these experiences convinced him that good, hardworking people were the victims of economic conditions over which they had no control and that government action was needed to create economic opportunity and security for all, regardless of race.

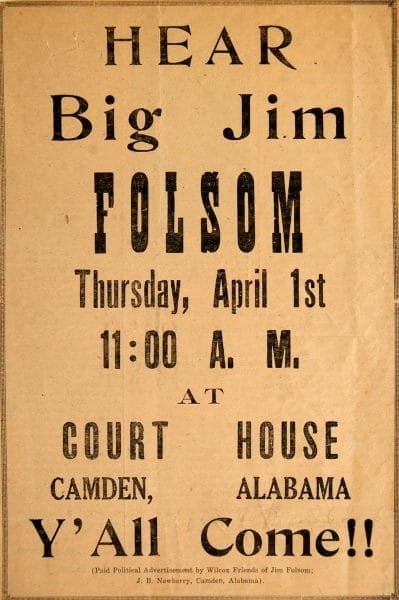

Folsom Campaign Poster

Folsom returned to Alabama in the early 1930s and ran and lost his first political campaign in 1933. He ran as an anti-Prohibitionist, known popularly as the “wet” position, for a place in the state convention that would determine Alabama’s stand on Prohibition. Folsom stated that he ran partly because he believed that Prohibition was a mistake but also to promote his name with an eye to future political races. Shortly after his defeat, he used family connections to win an appointment as head of the Marshall County Civil Works Administration relief program, which was part of Pres. Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal efforts. His aggressive and iconoclastic approach won him many admirers and foreshadowed his later administrative style as governor. It also probably led to his being eased out of his position in a 1934 reorganization. He then returned to Elba.

Folsom Campaign Poster

Folsom returned to Alabama in the early 1930s and ran and lost his first political campaign in 1933. He ran as an anti-Prohibitionist, known popularly as the “wet” position, for a place in the state convention that would determine Alabama’s stand on Prohibition. Folsom stated that he ran partly because he believed that Prohibition was a mistake but also to promote his name with an eye to future political races. Shortly after his defeat, he used family connections to win an appointment as head of the Marshall County Civil Works Administration relief program, which was part of Pres. Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal efforts. His aggressive and iconoclastic approach won him many admirers and foreshadowed his later administrative style as governor. It also probably led to his being eased out of his position in a 1934 reorganization. He then returned to Elba.

In 1936, Folsom married Sarah Carnley, daughter of populist Judge Jefferson A. Carnley; the couple would have two children. That same year, Folsom ran for Congress seeking to unseat the powerful chairman of the House Banking and Currency Committee, New Deal Congressman Henry B. Steagall. Campaigning to the ideological left of Steagall, he lost the election, ran against Steagall again in 1938, and lost again. Folsom then moved his family to Cullman, where he became the north Alabama representative for an insurance company founded by a brother-in-law.

James “Big Jim” Folsom, 1955

The move to North Alabama allowed Folsom to play on the “friends and neighbors” voting support present in Alabama’s one-party (Democratic) elections. Folsom was able to run a statewide campaign from essentially two politically and economically similar but geographically separated homes. Both the Wiregrass region of southeastern Alabama and much of North Alabama were characterized by small farms, relatively few African Americans, and strong populist traditions.

James “Big Jim” Folsom, 1955

The move to North Alabama allowed Folsom to play on the “friends and neighbors” voting support present in Alabama’s one-party (Democratic) elections. Folsom was able to run a statewide campaign from essentially two politically and economically similar but geographically separated homes. Both the Wiregrass region of southeastern Alabama and much of North Alabama were characterized by small farms, relatively few African Americans, and strong populist traditions.

Alabama’s midsection, known as the Black Belt for its relatively rich, dark soil, was home to large cotton plantations. Substantial majorities of Black Belt citizens were African Americans, but nearly all were prevented from voting by a combination of laws and intimidation. The owners of the largest Black Belt plantations were allied with major corporations based primarily in Jefferson County, particularly Birmingham, and collectively these two groups were known as the Big Mules. The 1901 Alabama Constitution served as a treaty between the urban and Black Belt Big Mules, and they used it to dominate the legislature and many governors until the 1960s. The Big Mules had one major objective—to prevent change.

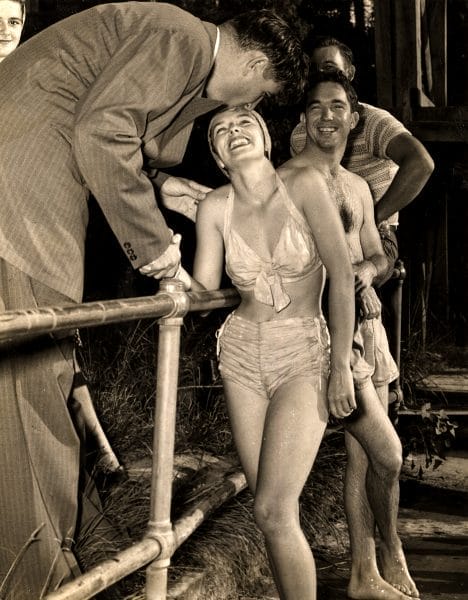

Folsom and Bathing Beauty

The Big Mules viewed taxes as a drain on their wealth and were wary of their potential use to fund programs that could help workers escape plantations, coal mines, and factories. They thus worked diligently to keep taxes low. Educating workers beyond the rudimentary knowledge needed to perform manual labor could make workers more mobile and independent, and so Big Mules opposed education reforms as well. The Big Mules were deeply racist and vigorously defended the segregation and voting discrimination that kept African American workers and citizens powerless. Malapportionment, built into the 1901 Constitution, gave the Big Mules almost complete control of the legislature, so they opposed reapportionment on a one-person-one-vote basis. Throughout his career Folsom favored virtually everything that the Big Mules opposed. A collision between the Big Mules and Folsom was inevitable.

Folsom and Bathing Beauty

The Big Mules viewed taxes as a drain on their wealth and were wary of their potential use to fund programs that could help workers escape plantations, coal mines, and factories. They thus worked diligently to keep taxes low. Educating workers beyond the rudimentary knowledge needed to perform manual labor could make workers more mobile and independent, and so Big Mules opposed education reforms as well. The Big Mules were deeply racist and vigorously defended the segregation and voting discrimination that kept African American workers and citizens powerless. Malapportionment, built into the 1901 Constitution, gave the Big Mules almost complete control of the legislature, so they opposed reapportionment on a one-person-one-vote basis. Throughout his career Folsom favored virtually everything that the Big Mules opposed. A collision between the Big Mules and Folsom was inevitable.

Folsom first ran for governor in 1942. The leading candidate died soon after the filing deadline, allowing Folsom to finish in second place behind the Black Belt candidate, Chauncey Sparks. At that time the state constitution forbade a governor from succeeding himself; so, a second place finish in one election constituted an advantage in the next election.

During World War II Folsom served briefly in the U.S. Army before being released because of his height (he was 6 foot 8 inches tall). He then joined the U.S. Merchant Marine, which he left when his wife Sarah died in 1944 from complications related to pregnancy. Two years later he met Jamelle Moore during his successful campaign for governor. The two were married in 1948, and the couple had seven children.

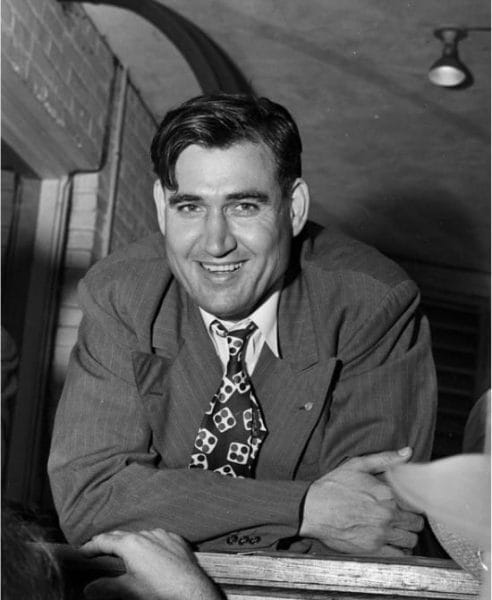

Folsom Campaigning, 1946

Folsom’s 1946 gubernatorial victory came after running an innovative campaign on an extraordinarily tight budget. In his speeches, he emphasized populist themes and racial harmony. In his inaugural address, he advocated the elimination of voting restrictions, fair apportionment of the state legislature, and more access to government positions for women. His first-term legislative proposals included: a convention to rewrite the 1901 Constitution; elimination of the poll tax; legislative reapportionment; placement of women on juries; and large highway bond issues. He also attempted to appoint voting registrars who would not discriminate against African Americans. The legislature killed virtually all of his proposals, and he was able to find relatively few individuals willing to serve as voting registrars on his terms.

Folsom Campaigning, 1946

Folsom’s 1946 gubernatorial victory came after running an innovative campaign on an extraordinarily tight budget. In his speeches, he emphasized populist themes and racial harmony. In his inaugural address, he advocated the elimination of voting restrictions, fair apportionment of the state legislature, and more access to government positions for women. His first-term legislative proposals included: a convention to rewrite the 1901 Constitution; elimination of the poll tax; legislative reapportionment; placement of women on juries; and large highway bond issues. He also attempted to appoint voting registrars who would not discriminate against African Americans. The legislature killed virtually all of his proposals, and he was able to find relatively few individuals willing to serve as voting registrars on his terms.

Folsom stood for election for governor again in 1954, the first time allowed by the 1901 Constitution. He ran against seven credible candidates and defeated them without a runoff. This time he also quietly ran a slate of pro-Folsom legislative candidates with substantial success. In the legislature, he won passage of a $40 million highway bond issue and a complex pension package. On the other hand, he failed to repeal the anti-labor union right-to-work law and was unable to stop most of the anti-desegregation bills that poured out of the legislature after the second U.S. Supreme CourtBrown v. Board of Education decision. The state legislature also blocked any attempts at a constitutional convention or legislative redistricting. Folsom ran for governor again in 1962 but was defeated by George C. Wallace, a former protégé who made racial politics the cornerstone of his campaign. Wallace’s victory was facilitated by Folsom’s disastrous live television advertisement in which he appeared to be drunk. There is some doubt regarding the cause of his behavior during that appearance. Folsom believed that he had been drugged, and his physician speculated that he had suffered the first of what would be several strokes. Nevertheless, his actions that night reflected two decades of very heavy and often public drinking. Folsom periodically ran for office from his home in Cullman thereafter, but without success. He died of a heart attack on November 21, 1987, and was buried in Cullman Cemetery in Cullman.

Folsom Family, 1958

Several of his children, including Melissa Folsom Boyen from his first marriage and Andrew Jackson “Jack” Folsom from his second marriage, have been active politically. His oldest son, James E. “Little Jim” Folsom Jr., has been the most successful, serving as public service commissioner and lieutenant governor, and succeeding to the governorship upon the felony conviction of Gov. Guy Hunt.

Folsom Family, 1958

Several of his children, including Melissa Folsom Boyen from his first marriage and Andrew Jackson “Jack” Folsom from his second marriage, have been active politically. His oldest son, James E. “Little Jim” Folsom Jr., has been the most successful, serving as public service commissioner and lieutenant governor, and succeeding to the governorship upon the felony conviction of Gov. Guy Hunt.

Big Jim Folsom exhibited vision uncommon among political leaders of his era in championing racial equality, women’s rights, legislative reapportionment, constitutional reform, and other progressive positions. As the Big Mules publicly fought Folsom, they were forced into revealing much about their operations and the ways they blocked political and constitutional change. Opposition to the kinds of ideas that Folsom advocated continued into the twenty-first century.

Note: This article is adapted from “James E. Folsom, Sr.” by Carl Grafton and Anne Permaloff, in Alabama Governors: A Political History of the State, edited by Samuel L. Webb and Margaret Armbrester (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001).

Further Reading

- Clem, Robert. Big Jim Folsom: The Two Faces of Populism. [Motion picture]. Waterfront Pictures Corporation and Foundation for a New Media, 1996.

- Grafton, Carl. “James E. Folsom’s 1946 Campaign.” Alabama Review 35 (July 1982): 170-199.

- ———. “James E. Folsom’s First Four Election Campaigns: Learning to Win by Losing.” Alabama Review 34 (July 1981): 163-183.

- ———. “James E. Folsom and Civil Liberties in Alabama.” Alabama Review 32 (January 1979): 3-27.

- Grafton, Carl, and Anne Permaloff. Big Mules and Branchheads: James E. Folsom and Political Power in Alabama. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1985.

- Sims, George. The Little Man’s Big Friend: James E. Folsom in Alabama Politics, 1946-1958. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1985.