World War II POW Camps in Alabama

During World War II, the state of Alabama was home to approximately 16,000 German prisoners of war (POWs) in 24 camps. The internment of these POWs significantly affected the social and economic history of Alabama. Indeed, with the German soldiers interacting with American guards and Alabama residents, the presence of Axis POWs brought the war to the Alabama homefront in a unique way.

German POWs Arriving at Camp Aliceville

In 1943, Allied forces defeated German and Italian armies in North Africa and captured 275,000 enemy soldiers. The logistical strain of securing these prisoners in North Africa prompted the U.S. military instead to move the POWs to the United States. The Army Corps of Engineers rapidly established camps in nearly every U.S. state to house them. As Allied armies penetrated Europe, hundreds of thousands of new prisoners were captured and also sent to the U.S. By 1945, the nation was host to more than 500 camps with some 425,000 POWs.

German POWs Arriving at Camp Aliceville

In 1943, Allied forces defeated German and Italian armies in North Africa and captured 275,000 enemy soldiers. The logistical strain of securing these prisoners in North Africa prompted the U.S. military instead to move the POWs to the United States. The Army Corps of Engineers rapidly established camps in nearly every U.S. state to house them. As Allied armies penetrated Europe, hundreds of thousands of new prisoners were captured and also sent to the U.S. By 1945, the nation was host to more than 500 camps with some 425,000 POWs.

The Army Corps of Engineers constructed Alabama’s first camps during the winter of 1942-1943. Army doctrine dictated that camps be built either at existing military bases or at sites distant from major cities and industrial centers, and military surveyors toured the state for suitable locations. The Army first selected two sites near the rural Alabama towns of Aliceville and Opelika, located in western Pickens County and eastern Lee County, respectively. Camp Aliceville would become Alabama’s largest POW camp, with a capacity for 6,000 prisoners, and Camp Opelika was capable of housing 3,000 POWs. As construction commenced, Army engineers established another camp for 3,000 prisoners at Fort McClellan, located in Calhoun County in northeastern Alabama. These three facilities served as the first major POW camps in Alabama during World War II. A fourth camp for 2,000 prisoners was added in February 1944, at what was then Fort Rucker in Dale County in south Alabama.

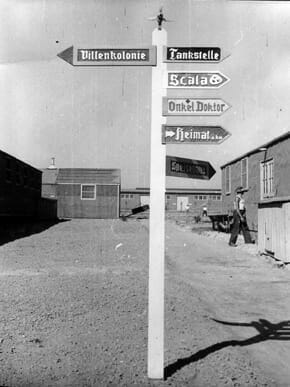

Camp Aliceville

Conditions within the camps conformed to the 1929 Geneva Conventions, which prescribed the parameters for the humane treatment of POWs. The American military stocked abundant provisions for the dietary and recreational needs of the prisoners. Life within the camps was so comfortable that one German prisoner wrote his family and described his temporary home as a “golden cage” and, conversely, some Alabama residents resented what they perceived as the POWs’ pampering while they endured rationing. Few POWs attempted to escape, and several of those who did were killed in the attempt. The comforts of camp life discouraged most escape attempts, however. Nonetheless, a few prisoners did manage to escape their American captors, most often by slipping away unnoticed during poorly guarded work details outside the camps. But escapees enjoyed brief freedom, as local police, Army investigators, and FBI agents quickly mobilized to track them down. No German prisoner in Alabama managed to elude capture for very long. The only dangers within the camps were the periodic political struggles among the prisoners. German soldiers committed to National Socialism (Nazism) fought with fellow prisoners who displayed anti-Nazi sentiments. To head off such ideological conflicts, American camp personnel separated Nazi and anti-Nazi factions within Alabama’s camps. Army officials then moved the two groups into special camps located outside of Alabama.

Camp Aliceville

Conditions within the camps conformed to the 1929 Geneva Conventions, which prescribed the parameters for the humane treatment of POWs. The American military stocked abundant provisions for the dietary and recreational needs of the prisoners. Life within the camps was so comfortable that one German prisoner wrote his family and described his temporary home as a “golden cage” and, conversely, some Alabama residents resented what they perceived as the POWs’ pampering while they endured rationing. Few POWs attempted to escape, and several of those who did were killed in the attempt. The comforts of camp life discouraged most escape attempts, however. Nonetheless, a few prisoners did manage to escape their American captors, most often by slipping away unnoticed during poorly guarded work details outside the camps. But escapees enjoyed brief freedom, as local police, Army investigators, and FBI agents quickly mobilized to track them down. No German prisoner in Alabama managed to elude capture for very long. The only dangers within the camps were the periodic political struggles among the prisoners. German soldiers committed to National Socialism (Nazism) fought with fellow prisoners who displayed anti-Nazi sentiments. To head off such ideological conflicts, American camp personnel separated Nazi and anti-Nazi factions within Alabama’s camps. Army officials then moved the two groups into special camps located outside of Alabama.

Prisoner Orchestra at Camp Opelika

Daily life for prisoners consisted largely of work and leisure. Prisoners assigned to labor details worked either inside the camp or at nearby farms or businesses, as allowed under the 1929 Geneva Convention. During their free time, prisoners participated in a variety of leisure activities, such as soccer, and many of the prisoners organized into teams. The wins and losses of soccer leagues at Camps Aliceville and McClellan were tracked in the camp newspapers. Each of the major camps established newspapers that featured prisoner essays, articles, short fiction, puzzles, and cartoons. Camp newspapers also featured reviews of prisoner musical performances. Prisoners also formed orchestras with instruments provided by the Army or donated by private charities. Some orchestras possessed remarkable performers. For instance, Camp Opelika’s orchestra included several professional musicians and was directed by a professor from the Musical Conservatory of Hanover. Prisoners also employed their creative talents in art studios, creating paintings, murals, sculptures, carvings, and other artwork.

Prisoner Orchestra at Camp Opelika

Daily life for prisoners consisted largely of work and leisure. Prisoners assigned to labor details worked either inside the camp or at nearby farms or businesses, as allowed under the 1929 Geneva Convention. During their free time, prisoners participated in a variety of leisure activities, such as soccer, and many of the prisoners organized into teams. The wins and losses of soccer leagues at Camps Aliceville and McClellan were tracked in the camp newspapers. Each of the major camps established newspapers that featured prisoner essays, articles, short fiction, puzzles, and cartoons. Camp newspapers also featured reviews of prisoner musical performances. Prisoners also formed orchestras with instruments provided by the Army or donated by private charities. Some orchestras possessed remarkable performers. For instance, Camp Opelika’s orchestra included several professional musicians and was directed by a professor from the Musical Conservatory of Hanover. Prisoners also employed their creative talents in art studios, creating paintings, murals, sculptures, carvings, and other artwork.

Each major camp established camp colleges, and prisoners could enroll in a wide variety of courses, including history, mathematics, the sciences, vocational courses, and preparatory classes for students seeking postwar careers in medicine, law, electrical engineering, and architecture. The educational opportunities provided by these camp colleges proved popular. For example, of Camp Opelika’s 3,000 prisoners, some 1,400 participated in coursework. Initially, prisoners taught the courses. Later, prisoners were permitted to enroll in correspondence courses from the University of Michigan and the University of Wisconsin. Army officials even contacted the University of Alabama and the Alabama Polytechnic Institute (now Auburn University) to discuss offering courses to the prisoners. But following Germany’s defeat and the discovery of the atrocities of the Holocaust, American military officials feared the presence of Nazis among the college instructors and took control of the camp colleges. New courses were introduced, emphasizing America’s history, society, and political structure, aimed at “re-educating” the prisoners. The prisoners received the best education about America, however, in their encounters with Americans while working on labor details.

Aliceville POW Camp

The economic dynamics of World War II resulted in the migration of millions of farm workers to cities, particularly among southern African Americans. This migration created labor shortages and potential shortfalls in agricultural production. German POWs provided this labor, which proved essential in harvesting Alabama’s important cash crops, such as cotton and peanuts. While fraternization between the prisoners and American guards and Alabama residents was forbidden, such nominal regulations proved ineffective. Alabamians often formed remarkable relationships with the prisoners working in their midst and expressed their friendship through gift-giving and, in a few occasions, invitations to their homes for meals. These friendships sometimes endured decades after the war.

Aliceville POW Camp

The economic dynamics of World War II resulted in the migration of millions of farm workers to cities, particularly among southern African Americans. This migration created labor shortages and potential shortfalls in agricultural production. German POWs provided this labor, which proved essential in harvesting Alabama’s important cash crops, such as cotton and peanuts. While fraternization between the prisoners and American guards and Alabama residents was forbidden, such nominal regulations proved ineffective. Alabamians often formed remarkable relationships with the prisoners working in their midst and expressed their friendship through gift-giving and, in a few occasions, invitations to their homes for meals. These friendships sometimes endured decades after the war.

Italian POWs at Fort Rucker

Prisoners received 80 cents a day for their labor, wages that could be spent on “luxury items” in commissaries within the camps. The need for prison labor led to the expansion of the camp system within the state. Small satellite camps were established throughout Alabama to facilitate the use of prison labor. Some camps, however, were temporary structures that existed for only a few weeks. By 1945, 20 satellite camps had been established in addition to the four major camps. The total population of the 24 camps was approximately 16,000 POWs. Compared with other larger and more populous states, Alabama possessed a considerable population of prisoners. Indeed, Alabama’s congressional delegation joined with other southern delegations to channel federal defense spending to their home constituencies, resulting in the Army placing most of the nation’s POW camps in the south and southwest.

Italian POWs at Fort Rucker

Prisoners received 80 cents a day for their labor, wages that could be spent on “luxury items” in commissaries within the camps. The need for prison labor led to the expansion of the camp system within the state. Small satellite camps were established throughout Alabama to facilitate the use of prison labor. Some camps, however, were temporary structures that existed for only a few weeks. By 1945, 20 satellite camps had been established in addition to the four major camps. The total population of the 24 camps was approximately 16,000 POWs. Compared with other larger and more populous states, Alabama possessed a considerable population of prisoners. Indeed, Alabama’s congressional delegation joined with other southern delegations to channel federal defense spending to their home constituencies, resulting in the Army placing most of the nation’s POW camps in the south and southwest.

Camp Aliceville Soccer Match

The POWs in Alabama’s camps were largely soldiers from the German Wehrmacht (armed forces), but there were some exceptions. A small number of Italian prisoners were interned for a time but were moved outside of Alabama following Italy’s surrender in 1943. Some prisoners, however, were neither citizens of Germany nor Italy. Combatants and citizens of nations overtaken by Germany often became unwilling conscripts for the German military and subsequently prisoners within Alabama’s POW camps. Such prisoners included citizens of Belgium, the former Czechoslovakia, France, the Netherlands, Latvia, Poland, and the former Soviet Union. In addition, there were several hundred prisoners from North Africa who were classified by the Army as “Arabs,” with no attempt to ascertain their national origin. Most remarkably, among the first prisoners to arrive at Camp Aliceville were a group of 17 Irish volunteers to the Wehrmacht.

Camp Aliceville Soccer Match

The POWs in Alabama’s camps were largely soldiers from the German Wehrmacht (armed forces), but there were some exceptions. A small number of Italian prisoners were interned for a time but were moved outside of Alabama following Italy’s surrender in 1943. Some prisoners, however, were neither citizens of Germany nor Italy. Combatants and citizens of nations overtaken by Germany often became unwilling conscripts for the German military and subsequently prisoners within Alabama’s POW camps. Such prisoners included citizens of Belgium, the former Czechoslovakia, France, the Netherlands, Latvia, Poland, and the former Soviet Union. In addition, there were several hundred prisoners from North Africa who were classified by the Army as “Arabs,” with no attempt to ascertain their national origin. Most remarkably, among the first prisoners to arrive at Camp Aliceville were a group of 17 Irish volunteers to the Wehrmacht.

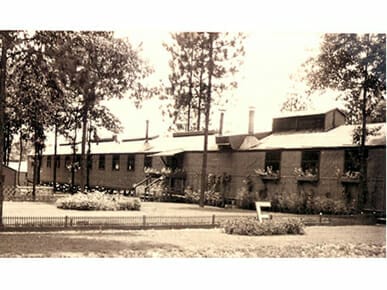

Camp Opelika

Following Germany’s surrender in the spring of 1945, Alabama’s POWs were repatriated to their devastated homelands. During the difficult years of postwar reconstruction, some German veterans appealed to their former “hosts” for assistance. Alabamians responded by sending food, clothing, and other forms of goodwill. In the decades after World War II, a number of former POWs returned to Alabama to reconnect with their past. Little exists of their former sites of imprisonment, however. By 1947 the camps had been dismantled. Today there is scant evidence indicating that the camps ever existed, except for a cemetery at Fort McClellan for 26 POWs who perished during the war. Nevertheless, reunions have been organized to bring together former prisoners, the American soldiers who guarded them, and the local citizens who befriended them. Two Alabama towns in particular have made special efforts to commemorate the POW experience in their communities. The Aliceville Museum and Cultural Center and the Museum of East Alabama in Opelika preserve and promote the World War II experience in Alabama, housing valuable artifacts and records of the camps. Their efforts preserve the German POW experience for future generations of Alabamians.

Camp Opelika

Following Germany’s surrender in the spring of 1945, Alabama’s POWs were repatriated to their devastated homelands. During the difficult years of postwar reconstruction, some German veterans appealed to their former “hosts” for assistance. Alabamians responded by sending food, clothing, and other forms of goodwill. In the decades after World War II, a number of former POWs returned to Alabama to reconnect with their past. Little exists of their former sites of imprisonment, however. By 1947 the camps had been dismantled. Today there is scant evidence indicating that the camps ever existed, except for a cemetery at Fort McClellan for 26 POWs who perished during the war. Nevertheless, reunions have been organized to bring together former prisoners, the American soldiers who guarded them, and the local citizens who befriended them. Two Alabama towns in particular have made special efforts to commemorate the POW experience in their communities. The Aliceville Museum and Cultural Center and the Museum of East Alabama in Opelika preserve and promote the World War II experience in Alabama, housing valuable artifacts and records of the camps. Their efforts preserve the German POW experience for future generations of Alabamians.

Further Reading

- Cook, Ruth Beaumont. Guests Behind the Barbed Wire: German POWs in the Small-Town South. Birmingham: Crane Hill Publishers, 2007.

- Hoole, W. Stanley. “Alabama’s World War II Prisoner of War Camps.” Alabama Review 20 (April 1967): 83-114.

- Hutchinson, Daniel. “Guests Behind Barbed Wire: German Prisoners of War Camps in Alabama During World War II.” M.A. thesis, University of Alabama at Birmingham, 2005.

- Killian, Albert. Prisoner of War Camp Opelika, Alabama, 1942-1945. Opelika, Ala..: Museum of East Alabama, 2002.

- Krammer, Arnold. Nazi Prisoners of War In America. New York: Stein & Day, 1996.