Fort Toulouse-Fort Jackson National Historic Park

Frontier Days at Fort Toulouse

Fort Toulouse was one of a series of forts built by the French to protect their holdings in southeastern North America from British infringement during the eighteenth century. The initial structure, located four miles from the head of the Alabama River on the Coosa River, stood near present-day Wetumpka in Elmore County. The site was renamed Fort Jackson in the early nineteenth century, when it was occupied by the United States, and played a role in the Creek War of 1813-1814 as the site of the meeting at which Creek leaders and Gen. Andrew Jackson signed the Treaty of Fort Jackson. Recently, archaeologists have excavated the remains of the fort, which has been reconstructed for visitors, and the site is now known as the Fort Toulouse National Historic Park.

Frontier Days at Fort Toulouse

Fort Toulouse was one of a series of forts built by the French to protect their holdings in southeastern North America from British infringement during the eighteenth century. The initial structure, located four miles from the head of the Alabama River on the Coosa River, stood near present-day Wetumpka in Elmore County. The site was renamed Fort Jackson in the early nineteenth century, when it was occupied by the United States, and played a role in the Creek War of 1813-1814 as the site of the meeting at which Creek leaders and Gen. Andrew Jackson signed the Treaty of Fort Jackson. Recently, archaeologists have excavated the remains of the fort, which has been reconstructed for visitors, and the site is now known as the Fort Toulouse National Historic Park.

Fort Toulouse

French administrator and explorer Jean-Baptiste de Le Moyne de Bienville, who would later become a very capable governor of Louisiana, proposed the fort in 1714. Fort Toulouse began its service as a frontier outpost for the French in 1717. The impetus for its establishment was the Yamasee War of 1715-1716, a conflict between local Indian tribes and South Carolina colonists that forced all British traders out of present-day Alabama. The fort, named for Adm. Louis Alexandre de Bourbon, Count of Toulouse, was initially constructed to extend the political, economic, and military reach of the French, who were based in Mobile. After the war, the French saw an opportunity to encroach on British trade and extend their influence among the Creeks. The fort was a natural meeting point for various peoples, including the anti-British faction of the Creek Nation.

Fort Toulouse

French administrator and explorer Jean-Baptiste de Le Moyne de Bienville, who would later become a very capable governor of Louisiana, proposed the fort in 1714. Fort Toulouse began its service as a frontier outpost for the French in 1717. The impetus for its establishment was the Yamasee War of 1715-1716, a conflict between local Indian tribes and South Carolina colonists that forced all British traders out of present-day Alabama. The fort, named for Adm. Louis Alexandre de Bourbon, Count of Toulouse, was initially constructed to extend the political, economic, and military reach of the French, who were based in Mobile. After the war, the French saw an opportunity to encroach on British trade and extend their influence among the Creeks. The fort was a natural meeting point for various peoples, including the anti-British faction of the Creek Nation.

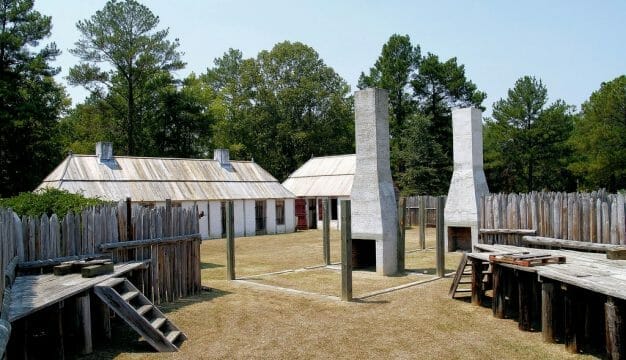

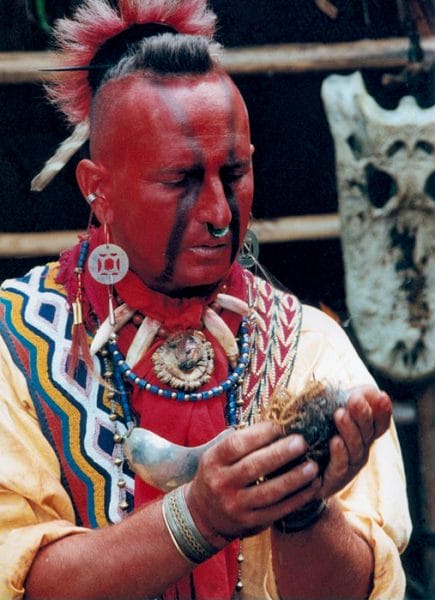

Historic Creek Re-enactor at Fort Toulouse

The British and the French called the fort by many names: “Post aux Alibamons,” “Fort des Alibamons,” “Fort Toulouse des Alibamons,” “Alabama Post,” and the “Alabama Fort.” Its physical layout was similar to other forts of the time period. Built of logs estimated to be one foot in diameter and nine feet in length, the original fort encompassed roughly 100 square yards. Archaeological excavations have uncovered three gates, a brick armory, a moat, and separate quarters for officers and enlisted men. The original plans for the fort are no longer in existence, but archaeological excavations have begun to reveal its layout. A watchtower, vital to the defense of the fort, was also added. Alabama’s hot and humid climate caused the fort’s wooden structures to rot quickly, and they had to be rebuilt at regular intervals. In 1721, just four years after its initial completion, the fort was already in very poor condition and had to be repaired. In 1733, the fort had to be entirely rebuilt because of rotting timber in the defensive walls; this reconstruction was completed in 1736. By 1748, Fort Toulouse was again rotting away and had to be relocated when erosion from the Coosa River threatened to plunge the fort into the river. It was rebuilt in 1751 and then for a final time in 1755.

Historic Creek Re-enactor at Fort Toulouse

The British and the French called the fort by many names: “Post aux Alibamons,” “Fort des Alibamons,” “Fort Toulouse des Alibamons,” “Alabama Post,” and the “Alabama Fort.” Its physical layout was similar to other forts of the time period. Built of logs estimated to be one foot in diameter and nine feet in length, the original fort encompassed roughly 100 square yards. Archaeological excavations have uncovered three gates, a brick armory, a moat, and separate quarters for officers and enlisted men. The original plans for the fort are no longer in existence, but archaeological excavations have begun to reveal its layout. A watchtower, vital to the defense of the fort, was also added. Alabama’s hot and humid climate caused the fort’s wooden structures to rot quickly, and they had to be rebuilt at regular intervals. In 1721, just four years after its initial completion, the fort was already in very poor condition and had to be repaired. In 1733, the fort had to be entirely rebuilt because of rotting timber in the defensive walls; this reconstruction was completed in 1736. By 1748, Fort Toulouse was again rotting away and had to be relocated when erosion from the Coosa River threatened to plunge the fort into the river. It was rebuilt in 1751 and then for a final time in 1755.

The normal military complement of the fort ranged from 15 to 30 men, depending on the changing demands of the French Empire. Given its small size and isolated location, Fort Toulouse frequently ran short of supplies and lagged in the new technologies the French had implemented in their armies stationed in more cosmopolitan locations. Because of Fort Toulouse’s remoteness, it was one of the last installations in the French Empire to receive new guns, improved artillery, and medical supplies. The problem of logistics overruled the importance of the fort and typically resulted in poor supply of the fort. The officers and soldiers of Fort Toulouse were ordered to maintain a valuable strategic area with a minimum of logistical and material support. These difficult conditions led to at least two mutinies within the first decade of the post’s existence. Both occurred when poorly paid French soldiers tried to escape the drudgery of frontier life and defect to the supposed glamour of the British colonies in the east. As time passed, the French policy changed. To limit desertion, they sent only the best officers and enlisted men to be garrisoned at Fort Toulouse. In addition, historians have found evidence that during the colonial period the French contracted with Swiss mercenaries to occupy the post, alongside the French soldiers.

Spinning Wheel at Fort Toulouse-Fort Jackson

Fort Toulouse acted as a commercial, religious, and diplomatic center for the French from 1717 until 1763. The fort also provided a permanent locale where French merchants could trade their goods with the Creeks for deerskins, thus strengthening the relationship between the two trading partners. In addition, Fort Toulouse, like most French forts, provided a base for Jesuit priests working to convert Native Americans to Roman Catholicism, the religion of the French Empire. The first Jesuit priest, Father Alexis (or Alexander) Xavier de Guyenne, of Orleans, France, arrived in 1727. During his three years in the region, Father Alexis evidently had some success in converting some local Native Americans and sought to expand his efforts, even suggesting to his superiors that they assign a priest to live among the Coweta Indians. In addition to their religious roles, French Jesuits on the frontier often acted as diplomats, and Father Alexis’s work at Fort Toulouse followed this pattern as well. Through gifts such as French goods, the French military officers and clergy attempted to sway local Native American leaders to their side in their various conflicts with the British.

Spinning Wheel at Fort Toulouse-Fort Jackson

Fort Toulouse acted as a commercial, religious, and diplomatic center for the French from 1717 until 1763. The fort also provided a permanent locale where French merchants could trade their goods with the Creeks for deerskins, thus strengthening the relationship between the two trading partners. In addition, Fort Toulouse, like most French forts, provided a base for Jesuit priests working to convert Native Americans to Roman Catholicism, the religion of the French Empire. The first Jesuit priest, Father Alexis (or Alexander) Xavier de Guyenne, of Orleans, France, arrived in 1727. During his three years in the region, Father Alexis evidently had some success in converting some local Native Americans and sought to expand his efforts, even suggesting to his superiors that they assign a priest to live among the Coweta Indians. In addition to their religious roles, French Jesuits on the frontier often acted as diplomats, and Father Alexis’s work at Fort Toulouse followed this pattern as well. Through gifts such as French goods, the French military officers and clergy attempted to sway local Native American leaders to their side in their various conflicts with the British.

During the French and Indian War (part of the Seven Years War in Europe) between France and England, which began over trade and territorial claims in 1754, the bulk of the fighting in North America took place in the New York and Pennsylvania colonies and Canada. Although on the periphery, Fort Toulouse was an integral stronghold for the French. French officer and political negotiator Henrí Montault de Monbéraut de Saint-Çivier was given command in 1755 and oversaw efforts to refortify and reinforce the installation to bring the fort’s complement to around 50 men in 1756. The British, however, did not invade Louisiana during the war and the garrison at Fort Toulouse did not engage in combat, and Monbéraut was relieved of his command in 1759. The general consensus among historians is that despite the lack of supplies and trade goods during this time, resulting from a British naval blockade, the local Indians sided with the French. When the British ultimately defeated the French, Fort Toulouse and its environs were ceded to the British as outlined in the 1763 Treaty of Paris. The French vacated the fort sometime between November 1763 and January 1764. Following the French departure, the British decided that it was not necessary to garrison troops at Fort Toulouse and the fort fell into disrepair.

Fort Jackson

The next major use of the location was during the War of 1812 and the Creek War of 1813-1814, which was fought largely in Alabama and the surrounding areas. After the Battle of Horseshoe Bend, Jackson ordered his troops to construct a fort on the site of old Fort Toulouse; they named it in honor of Jackson. There, with Creek leaders, he concluded the Treaty of Fort Jackson that ceded more than 21 million acres of central Alabama and southern Georgia to the United States. The document not only ended the Creek Wars but also permitted Jackson to turn his attention to the other threat, the British.

Fort Jackson

The next major use of the location was during the War of 1812 and the Creek War of 1813-1814, which was fought largely in Alabama and the surrounding areas. After the Battle of Horseshoe Bend, Jackson ordered his troops to construct a fort on the site of old Fort Toulouse; they named it in honor of Jackson. There, with Creek leaders, he concluded the Treaty of Fort Jackson that ceded more than 21 million acres of central Alabama and southern Georgia to the United States. The document not only ended the Creek Wars but also permitted Jackson to turn his attention to the other threat, the British.

The Fort Toulouse site was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1960, and the Alabama Historical Commission gained possession of it in 1971. Since then, teams of professional and amateur archaeologists have excavated the site and uncovered nearly the entire foundation of the second Fort Toulouse designed and rebuilt in 1748. Now known as Fort Toulouse-Fort Jackson National Historic Park, the site hosts various events on most weekends from the spring to mid fall, with living history demonstrations that recreate French, Native American, and colonial American life on the frontier.

Further Reading

- Thomas, Daniel H. Fort Toulouse: The French Outpost at the Alabamas on the Coosa. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1989.