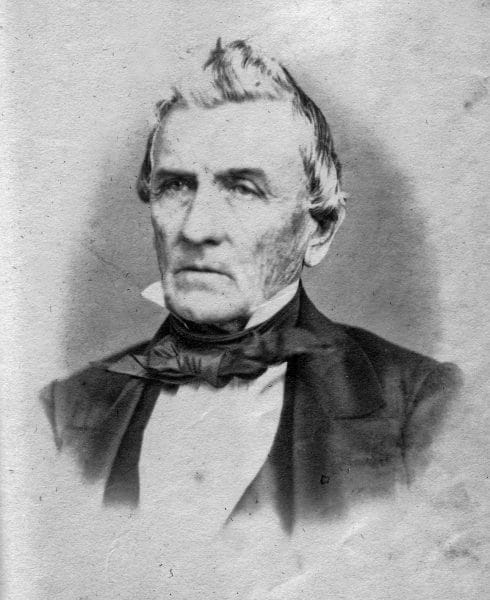

Benjamin Fitzpatrick (1841-45)

Benjamin Fitzpatrick

Governor and U.S. senator Benjamin Fitzpatrick (1802-1869), like most of his predecessors in the governor‘s chair, was associated with the Jacksonian wing of the Alabama Democratic Party, but he also led a loosely organized faction of the party sometimes known as the “Montgomery Regency,” whose members were united more around family and personal ties than ideology. Fitzpatrick’s two terms as governor, like those of his three immediate predecessors, were dominated by questions surrounding the state-owned Bank of Alabama, which was still teetering on the verge of bankruptcy as a result of the depression that followed the Panic of 1837. During his senatorial career, Fitzpatrick was a Democratic Party loyalist, and resisted the rise of Yanceyite southern rights extremism.

Benjamin Fitzpatrick

Governor and U.S. senator Benjamin Fitzpatrick (1802-1869), like most of his predecessors in the governor‘s chair, was associated with the Jacksonian wing of the Alabama Democratic Party, but he also led a loosely organized faction of the party sometimes known as the “Montgomery Regency,” whose members were united more around family and personal ties than ideology. Fitzpatrick’s two terms as governor, like those of his three immediate predecessors, were dominated by questions surrounding the state-owned Bank of Alabama, which was still teetering on the verge of bankruptcy as a result of the depression that followed the Panic of 1837. During his senatorial career, Fitzpatrick was a Democratic Party loyalist, and resisted the rise of Yanceyite southern rights extremism.

Benjamin Fitzpatrick was born in Greene County, Georgia, on June 30, 1802, the son of William Fitzpatrick, who served as a Georgia state legislator for 19 years, and Anne Phillips Fitzpatrick. Benjamin was orphaned at age seven and was reared by his older brothers and sisters. He received little formal schooling and led a rather knockabout youth. When he was 14, he came alone to what was then the Mississippi Territory. He obtained work as a clerk in a Wetumpka store, was employed as a deputy sheriff, and read law under Montgomery mayor Nimrod E. Benson. He was admitted to the Alabama State Bar in 1821 at age 19 and was immediately elected by the new state legislature as the circuit solicitor for the Montgomery area. He was reelected to this position in 1825, defeating future congressman Samuel W. Mardis.

In 1827 Fitzpatrick married Sarah Terry Elmore, a member of the wealthy and prominent family for whom Elmore County was later named. The couple would have six sons. The marriage brought Fitzpatrick a large plantation across the Alabama River from Montgomery, and he declined reelection as a circuit solicitor to devote his efforts to overseeing its operations. These efforts turned out to be quite lucrative. In 1830, Fitzpatrick owned 24 enslaved African Americans. By 1850 he would own 106. His real estate in 1860 would be valued at $60,000 and his personal property at $125,000.

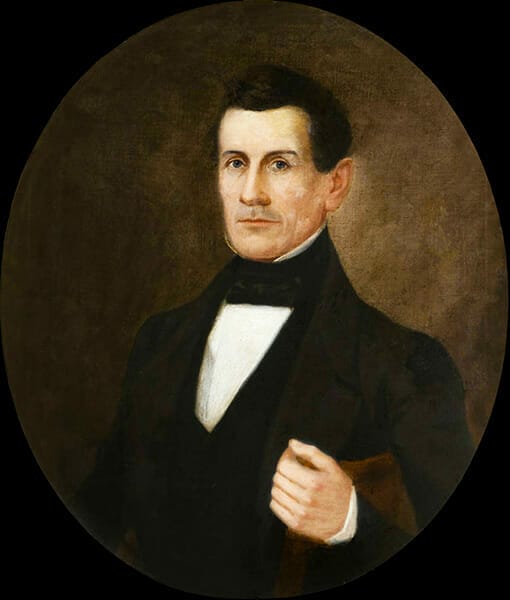

Arthur P. Bagby

After the death of his wife in 1837, Fitzpatrick turned his attention increasingly to politics. That year, he was a candidate for the gubernatorial nomination in the Democratic legislative caucus but was narrowly defeated by Arthur P. Bagby. In 1840 he served as a Democratic candidate for presidential elector and conducted an impressive statewide canvass for Martin Van Buren. In 1841 the Democrats nominated him for governor, and he was elected over James W. McLung, the Whig nominee, taking 57 percent of the vote.

Arthur P. Bagby

After the death of his wife in 1837, Fitzpatrick turned his attention increasingly to politics. That year, he was a candidate for the gubernatorial nomination in the Democratic legislative caucus but was narrowly defeated by Arthur P. Bagby. In 1840 he served as a Democratic candidate for presidential elector and conducted an impressive statewide canvass for Martin Van Buren. In 1841 the Democrats nominated him for governor, and he was elected over James W. McLung, the Whig nominee, taking 57 percent of the vote.

During his campaign, Fitzpatrick assured Alabama voters that he had never been either a director or a debtor of the failing Bank of Alabama and promised to approach the financial crisis without any pro-bank bias. Fitzpatrick was by nature a cautious and conservative man, and he initially wanted to save the indebted bank. It was primarily the Jacksonian commitment to inactive government, rather than its hostility to corporate capitalism, that had attracted him to the Democratic Party. In Fitzpatrick’s first message to the legislature, he urged the liquidation of the extraordinarily mismanaged branch at Mobile, but merely sought to reform the main bank and its other three branches. Radical Jacksonians, who hated all banks, joined with Whigs, who opposed the state ownership of a bank, to produce an incongruous legislative majority for more extreme action. In early 1843, Fitzpatrick reluctantly signed legislation to liquidate all four of the branches and to preserve only the main bank at Tuscaloosa.

Benjamin Fitzpatrick

To Fitzpatrick’s surprise, this action proved to have broad popular support, and in the summer of 1843 he was reelected to a second term without any opposition. He then assumed a hardline antibank stance. When the bank’s charter expired in January 1845, Fitzpatrick refused to support its renewal and signed a bill eliminating state involvement with the banking system altogether. Nevertheless, he adamantly opposed radical Democrat efforts to repudiate the state debt, which had been contracted in large part to keep the bank in operation. When he left the governorship that year, the legislature chose him as one of the three commissioners supervising the bank’s final liquidation. In 1847, he married Aurelia Blassingame of Marion, with whom he had a seventh son.

Benjamin Fitzpatrick

To Fitzpatrick’s surprise, this action proved to have broad popular support, and in the summer of 1843 he was reelected to a second term without any opposition. He then assumed a hardline antibank stance. When the bank’s charter expired in January 1845, Fitzpatrick refused to support its renewal and signed a bill eliminating state involvement with the banking system altogether. Nevertheless, he adamantly opposed radical Democrat efforts to repudiate the state debt, which had been contracted in large part to keep the bank in operation. When he left the governorship that year, the legislature chose him as one of the three commissioners supervising the bank’s final liquidation. In 1847, he married Aurelia Blassingame of Marion, with whom he had a seventh son.

Although the bank issue dominated Fitzpatrick’s two terms as governor, he also advocated other actions to limit the power of government. In his first inaugural address, Fitzpatrick succinctly stated the antebellum attitude toward taxation: “The essence of modern oppression is taxation. The measure of popular liberty may be found in the amount of money which is taken from the people to support the government; when the amount is increased beyond the requirement of a rigid economy, the government becomes profligate and oppressive.” Consistent with this antigovernment view, Fitzpatrick championed a constitutional amendment that changed meetings of the legislature from annual to biennial sessions.

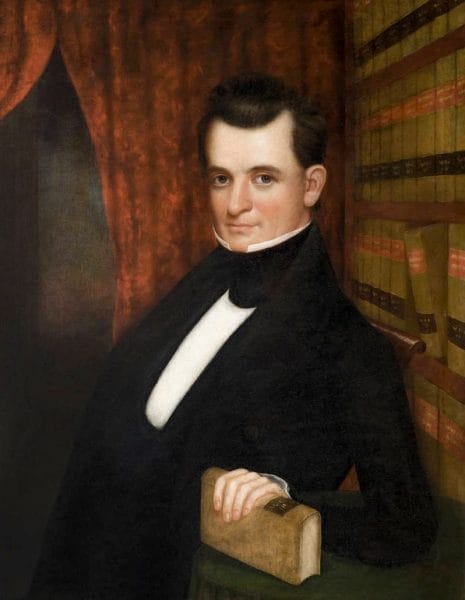

Reuben Chapman, 1847

In November 1848, Gov. Reuben Chapman appointed Fitzpatrick to the vacancy in the U.S. Senate created by the death of Dixon Hall Lewis, and when the state legislature met in 1849, the Democratic caucus, under the influence of the Montgomery Regency, chose him as its nominee for the full term. Drawing upon the continuing sectionalism within the state, a group of north Alabama Democrats, led by Jeremiah Clemens of Huntsville, bolted the caucus on the contention that Fitzpatrick’s election would unfairly give both Senate seats to south Alabama. On the sixth ballot, Whig members threw their votes to Clemens, and Fitzpatrick was defeated. In January 1853, Gov. Henry W. Collier appointed Fitzpatrick to the Senate once again, this time to succeed William Rufus King, who had been elected vice president of the United States. Fitzpatrick was overwhelmingly elected to the seat by the legislature in November, and in 1855, he was reelected to a full term over a Know-Nothing candidate.

Reuben Chapman, 1847

In November 1848, Gov. Reuben Chapman appointed Fitzpatrick to the vacancy in the U.S. Senate created by the death of Dixon Hall Lewis, and when the state legislature met in 1849, the Democratic caucus, under the influence of the Montgomery Regency, chose him as its nominee for the full term. Drawing upon the continuing sectionalism within the state, a group of north Alabama Democrats, led by Jeremiah Clemens of Huntsville, bolted the caucus on the contention that Fitzpatrick’s election would unfairly give both Senate seats to south Alabama. On the sixth ballot, Whig members threw their votes to Clemens, and Fitzpatrick was defeated. In January 1853, Gov. Henry W. Collier appointed Fitzpatrick to the Senate once again, this time to succeed William Rufus King, who had been elected vice president of the United States. Fitzpatrick was overwhelmingly elected to the seat by the legislature in November, and in 1855, he was reelected to a full term over a Know-Nothing candidate.

Henry Watkins Collier

In the Senate, Fitzpatrick devoted most of his attention to public land policy. He strongly supported the reduction of public land prices and fought for preemption rights for squatters on lands the federal government had granted to railroads. He played an active role in obtaining the passage of the Homestead Bill of 1860, but in an act of party loyalty refused to vote to override Pres. James Buchanan’s veto of it. He was the U.S. Senate’s president pro tempore from December 1857 to January 1861, when Alabama seceded from the United States.

Henry Watkins Collier

In the Senate, Fitzpatrick devoted most of his attention to public land policy. He strongly supported the reduction of public land prices and fought for preemption rights for squatters on lands the federal government had granted to railroads. He played an active role in obtaining the passage of the Homestead Bill of 1860, but in an act of party loyalty refused to vote to override Pres. James Buchanan’s veto of it. He was the U.S. Senate’s president pro tempore from December 1857 to January 1861, when Alabama seceded from the United States.

In the late 1850s, Fitzpatrick was caught between those who supported immediate secession and those who wanted to take a more moderate course. He had long been an enthusiastic advocate of Illinois senator Stephen A. Douglas’s doctrine of popular sovereignty in the territories, and this earned him the active opposition of William Lowndes Yancey and his following of young and ambitious southern-rights Democrats. When Fitzpatrick sought early reelection to the Senate in 1859, Yanceyites in the state legislature blocked the resolution to call the election. Not surprisingly, this action made Fitzpatrick and Yancey bitter enemies.

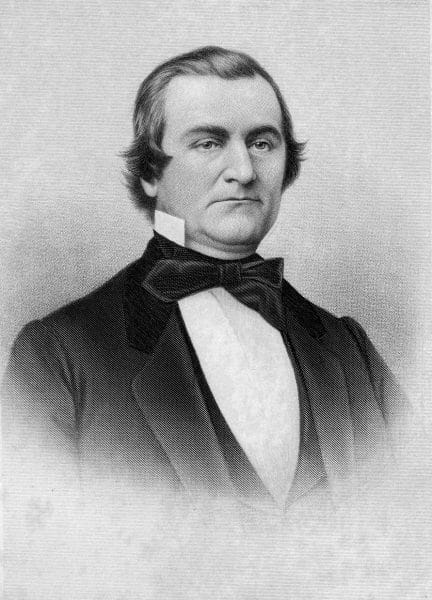

William Lowndes Yancey Portrait

In the summer of 1860, the Baltimore Democratic National Convention nominated Fitzpatrick for vice president on a ticket with the Unionist Douglas. Fitzpatrick initially gave his consent to the candidacy but upon his return home discovered how unpopular Douglas was in Alabama and declined the nomination. This action did nothing to mollify the hostile southern rights men, however. The Yanceyites advocated immediate, separate state secession, and Fitzpatrick sought to defeat them by instead endorsing cooperative, joint secession of all the southern states. Fitzpatrick was unable to generate substantial support for his proposal outside of Alabama’s northern counties. When the convention adopted the secession ordinance, Fitzpatrick resigned his Senate seat on January 21, 1861, and returned to his plantation. Two years later, when his name was placed in nomination for a seat in the Confederate Senate, southern-rights radicals, who remained irreconcilably opposed to Fitzpatrick, helped to defeat him.

William Lowndes Yancey Portrait

In the summer of 1860, the Baltimore Democratic National Convention nominated Fitzpatrick for vice president on a ticket with the Unionist Douglas. Fitzpatrick initially gave his consent to the candidacy but upon his return home discovered how unpopular Douglas was in Alabama and declined the nomination. This action did nothing to mollify the hostile southern rights men, however. The Yanceyites advocated immediate, separate state secession, and Fitzpatrick sought to defeat them by instead endorsing cooperative, joint secession of all the southern states. Fitzpatrick was unable to generate substantial support for his proposal outside of Alabama’s northern counties. When the convention adopted the secession ordinance, Fitzpatrick resigned his Senate seat on January 21, 1861, and returned to his plantation. Two years later, when his name was placed in nomination for a seat in the Confederate Senate, southern-rights radicals, who remained irreconcilably opposed to Fitzpatrick, helped to defeat him.

With the end of the Civil War, Fitzpatrick was elected to represent Autauga County in the constitutional convention of 1865, summoned under the terms of Presidential Reconstruction and dominated by the former opponents of secession. When the delegates met, Fitzpatrick was unanimously chosen the convention’s president. But this proved to be his last participation in public life. The constitution produced by the convention was voided, and Fitzpatrick himself was disfranchised by the terms of the Military Reconstruction Acts of 1867. He died at his plantation on November 21, 1869. The Benjamin Fitzpatrick Bridge over the Tallapoosa River in Tallassee, Elmore County, is named in his honor.

Note: This entry was adapted with permission from Alabama Governors: A Political History of the State, edited by Samuel L. Webb and Margaret Armbrester (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001).

Further Reading

- Abrams, David L. “The State Bank of Alabama, 1841-1845.” Master’s thesis, Auburn University, 1965.

- Duncan, William W. “The Life of Benjamin Fitzpatrick.” Master’s thesis, University of Alabama, 1930.

- Thornton, J. Mills, III. Politics and Power in a Slave Society: Alabama, 1800-1860. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1978.