World War II and Alabama

World War II and its aftermath changed the face of American culture, and this was equally true in Alabama. The state had already begun its recovery after the Great Depression, but the war brought major industrial expansion, dramatic population shifts, and new opportunities in the workforce for African Americans and women. Boom times followed, with sometimes dubious consequences for many Alabama communities, and the effects of these changes continue to evolve and shape the state and its inhabitants.

Fighting Alabamians

Alabama National Guard in World War II

In the late 1930s, the aggressive actions taken by the future Axis powers—Germany, Italy, and Japan—led Pres. Franklin Delano Roosevelt to urge Congress and the American public to support sharply increased defense spending, expanding the armed forces, and establishing military conscription. After Germany’s rapid conquest of Poland in September 1939, and France, Belgium, and the Netherlands the next summer, Congress appropriated $5 billion for defense, passed legislation to create a military draft, and authorized Roosevelt to call up the Army Reserves and federalize the National Guard. Toward the end of 1940, nearly 4,000 Alabama National Guardsmen joined men from Mississippi, Louisiana, and Florida in the Thirty-first Infantry (Dixie) Division at Camp Blanding, Florida. By the summer of 1941, nearly 350,000 Alabama men between the ages of 21 and 35 had registered with draft boards.

Alabama National Guard in World War II

In the late 1930s, the aggressive actions taken by the future Axis powers—Germany, Italy, and Japan—led Pres. Franklin Delano Roosevelt to urge Congress and the American public to support sharply increased defense spending, expanding the armed forces, and establishing military conscription. After Germany’s rapid conquest of Poland in September 1939, and France, Belgium, and the Netherlands the next summer, Congress appropriated $5 billion for defense, passed legislation to create a military draft, and authorized Roosevelt to call up the Army Reserves and federalize the National Guard. Toward the end of 1940, nearly 4,000 Alabama National Guardsmen joined men from Mississippi, Louisiana, and Florida in the Thirty-first Infantry (Dixie) Division at Camp Blanding, Florida. By the summer of 1941, nearly 350,000 Alabama men between the ages of 21 and 35 had registered with draft boards.

Napier Field

Approximately 300,000 Alabama men donned service uniforms during the war, and tens of thousands of servicemen trained in the state. Many women volunteered for one of the military auxiliaries, such as the Women’s Army Corps or the Army Nurse Corps. More than 6,000 Alabamians lost their lives in military service: 4,600 in combat and 1,600 in non-combat situations. Twelve of the 469 recipients of the Medal of Honor in World War II were born in Alabama or entered service there. Army captain Charles W. “Gordo” Davis, so nicknamed after his hometown in Pickens County, led his troops into Japanese fire on Guadalcanal and earned a Medal of Honor. Born in Bessemer, Navy commander David McCampbell, of the renowned Air Group Fifteen on the carrier USS Enterprise, downed 34 Japanese planes, more than any other Navy pilot. Howard Gilmore, born in Selma and commander of the USS Growler, became the first submarine commander in World War II to receive (posthumously) the Medal of Honor.

Napier Field

Approximately 300,000 Alabama men donned service uniforms during the war, and tens of thousands of servicemen trained in the state. Many women volunteered for one of the military auxiliaries, such as the Women’s Army Corps or the Army Nurse Corps. More than 6,000 Alabamians lost their lives in military service: 4,600 in combat and 1,600 in non-combat situations. Twelve of the 469 recipients of the Medal of Honor in World War II were born in Alabama or entered service there. Army captain Charles W. “Gordo” Davis, so nicknamed after his hometown in Pickens County, led his troops into Japanese fire on Guadalcanal and earned a Medal of Honor. Born in Bessemer, Navy commander David McCampbell, of the renowned Air Group Fifteen on the carrier USS Enterprise, downed 34 Japanese planes, more than any other Navy pilot. Howard Gilmore, born in Selma and commander of the USS Growler, became the first submarine commander in World War II to receive (posthumously) the Medal of Honor.

Holland McTyeire Smith

Several career officers from Alabama played exceptionally noteworthy roles in the war. Marine general Holland “Howlin’ Mad” Smith of Russell County is recognized as the “father” of modern amphibious warfare. John Persons, a Birmingham banker and commander of the Thirty-first Dixie Division, which fought in the Pacific theater, was one of only two National Guard generals to lead troops into combat in World War II. Asa Duncan, a Colbert County native, served as chief of staff for Gen. Carl A. Spaatz, commander of the Eighth Air Force, which flew bombing raids from British airfields against industrial and military targets on the European continent.

Holland McTyeire Smith

Several career officers from Alabama played exceptionally noteworthy roles in the war. Marine general Holland “Howlin’ Mad” Smith of Russell County is recognized as the “father” of modern amphibious warfare. John Persons, a Birmingham banker and commander of the Thirty-first Dixie Division, which fought in the Pacific theater, was one of only two National Guard generals to lead troops into combat in World War II. Asa Duncan, a Colbert County native, served as chief of staff for Gen. Carl A. Spaatz, commander of the Eighth Air Force, which flew bombing raids from British airfields against industrial and military targets on the European continent.

John C. Persons

Many other Alabamians made unique contributions to the war effort, including Lt. Tom Borders, who piloted his B-17 Birmingham Blitzkrieg in the Eighth Air Force’s first sortie against enemy targets. His all-Alabama crew is credited with being the first in the Eighth Air Force to down a German plane. Notable among those Alabamians who served were the five Crommelin brothers from Wetumpka, all of whom served in the Pacific Theater. Two lost their lives as pilots during the war, and the eldest, John, served as flight officer on the carrier Enterprise and later as chief of staff of a carrier task force. Herbert Carter, in the first class of African American pilots to break the race barrier in military aviation, earned his wings at the Tuskegee Army Air Field and flew with the Ninety-ninth Pursuit Squadron in the North African and Italian campaigns. Nancy Batson from Birmingham, an early member of the Women’s Air Service Pilots, ferried military aircraft around the country to modification plants or ports of embarkation. Marine private and Mobile native Eugene Sledge authored With the Old Breed at Peleliu and Okinawa, a postwar memoir about his horrific combat experiences in the Pacific campaign now regarded as a classic of combat literature.

John C. Persons

Many other Alabamians made unique contributions to the war effort, including Lt. Tom Borders, who piloted his B-17 Birmingham Blitzkrieg in the Eighth Air Force’s first sortie against enemy targets. His all-Alabama crew is credited with being the first in the Eighth Air Force to down a German plane. Notable among those Alabamians who served were the five Crommelin brothers from Wetumpka, all of whom served in the Pacific Theater. Two lost their lives as pilots during the war, and the eldest, John, served as flight officer on the carrier Enterprise and later as chief of staff of a carrier task force. Herbert Carter, in the first class of African American pilots to break the race barrier in military aviation, earned his wings at the Tuskegee Army Air Field and flew with the Ninety-ninth Pursuit Squadron in the North African and Italian campaigns. Nancy Batson from Birmingham, an early member of the Women’s Air Service Pilots, ferried military aircraft around the country to modification plants or ports of embarkation. Marine private and Mobile native Eugene Sledge authored With the Old Breed at Peleliu and Okinawa, a postwar memoir about his horrific combat experiences in the Pacific campaign now regarded as a classic of combat literature.

The Home Front

Alabamians on the home front contributed to the war effort in countless ways. Communities mounted scrap drives to collect metals and rubber. Red Cross chapters and other groups made bandages, knitted sweaters, and collected clothes for people injured or displaced during the war. Many more sent gift packages, letters, and newsletters to hometown men and women in the military. Montgomery’s Soldier’s Center, later known as the Army-Navy USO Club, was the first civilian-run servicemen’s club in the United States. Other Alabama towns, churches, and civic groups established similar clubs for servicemen and defense workers. Every county in Alabama achieved its quota—a national record—in each of the federal government’s eight war bond campaigns.

World War II Bond Drive

Rationing began in 1942. Limits on the purchase of rubber tires and gasoline reduced mobility, and hitchhiking became a common means of transportation. Public opinion polls reported that people missed sugar more than any other rationed good, including shoes, meats, and coffee. In order to save electricity, daylight savings time was introduced. The government imposed a coastal dim-out, implemented beach patrols, and restricted fishing and recreational boating in the Gulf of Mexico. For the most part, Alabamians accepted these and other wartime inconveniences without complaint.

World War II Bond Drive

Rationing began in 1942. Limits on the purchase of rubber tires and gasoline reduced mobility, and hitchhiking became a common means of transportation. Public opinion polls reported that people missed sugar more than any other rationed good, including shoes, meats, and coffee. In order to save electricity, daylight savings time was introduced. The government imposed a coastal dim-out, implemented beach patrols, and restricted fishing and recreational boating in the Gulf of Mexico. For the most part, Alabamians accepted these and other wartime inconveniences without complaint.

World War II was not just waged “over there” in the Pacific, North Africa, and Europe. The war erupted off the Alabama coast in May 1942 when German submarines arrived in the Gulf of Mexico. During the next two months the gulf was one of the most dangerous places in the world for Allied shipping. Between May 1942 and December 1943, German U-boats sank nearly 50 freighters and tankers in the Gulf of Mexico.

Alabamians on the homefront got their first glimpses of the enemy a year later, in the summer of 1943, when German prisoners of war (POWs) began arriving. Four major POW camps—Aliceville, Opelika, Camp Rucker, and Fort McClellan—and numerous smaller camps housed thousands of war prisoners captured when German and Italian forces surrendered in North Africa. Local farmers, lumbermen, and businessmen often contracted with camp officials to hire war prisoners, who were paid in scrip (tokens that could only be redeemed at the camp store) for their labor.

A Changing Landscape

The state—favored by a good climate and cheap land—offered ideal sites for U.S. military bases. Fort McClellan, established in Anniston in 1917, became a major induction center. Camp Rucker, constructed in 1942 near Ozark in Dale County, was Alabama’s other large infantry training center. Camp Sibert near Gadsden opened that same year for chemical warfare training.

Brookley Field

From the days of the Wright brothers, Alabama has played a conspicuous role in aviation. During World War II, so many aviators trained at Maxwell Field that it came to be said that the “road to Tokyo” led through Montgomery. Gunter Field, Montgomery’s municipal airport, became a flight school, and new aviation training facilities were built, including Craig Field outside Selma, Napier Field near Dothan, and Courtland Field in the Tennessee River Valley. One of the most important and pioneering projects was the Tuskegee Army Air Field, where nearly 1,000 African Americans received their wings as pilots. Brookley Field on Mobile Bay trained air corps glider pilots and housed both the Southeast Army Air Depot, which supplied military bases in the Southeast and the Caribbean, and the Mobile Air Service Command, which modified and repaired military aircraft.

Brookley Field

From the days of the Wright brothers, Alabama has played a conspicuous role in aviation. During World War II, so many aviators trained at Maxwell Field that it came to be said that the “road to Tokyo” led through Montgomery. Gunter Field, Montgomery’s municipal airport, became a flight school, and new aviation training facilities were built, including Craig Field outside Selma, Napier Field near Dothan, and Courtland Field in the Tennessee River Valley. One of the most important and pioneering projects was the Tuskegee Army Air Field, where nearly 1,000 African Americans received their wings as pilots. Brookley Field on Mobile Bay trained air corps glider pilots and housed both the Southeast Army Air Depot, which supplied military bases in the Southeast and the Caribbean, and the Mobile Air Service Command, which modified and repaired military aircraft.

Alabama also played an indirect but critically important role in the manufacture of military aircraft. The state contained two of the nation’s five plants that played a part in the manufacture of aluminum, the most crucial metal in aircraft production, a Reynolds plant at Listerhill in the Tennessee Valley and, more important, an Aluminum Company of America (Alcoa) plant at the Alabama State Docks in Mobile. By 1943 the Mobile facility was producing 34 percent of the industry’s entire output. Alcoa also operated a fleet of 29 company-owned vessels and dozens of chartered vessels to haul bauxite (a mineral used in making aluminum) from South America to the Mobile plant. The Alcoa plant was among the potential targets of German saboteurs arrested and executed in the summer of 1942.

Shifting Populations

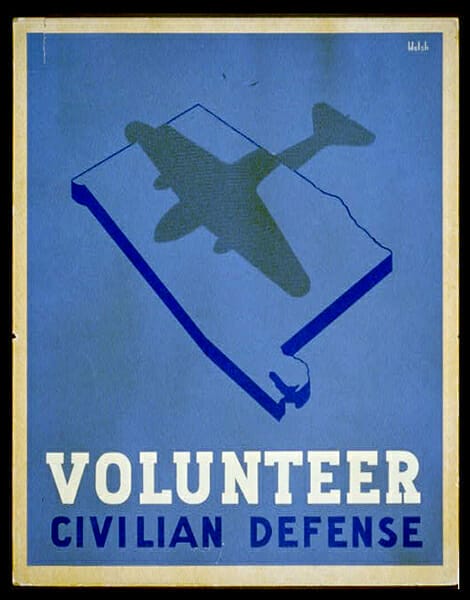

Recruitment Poster

The war produced enormous demographic changes in Alabama. Lured by the prospect of better paying jobs, thousands of Alabamians and workers from nearby states flocked into boom towns such as Mobile, Montgomery, and Huntsville. Approximately 10 percent of Alabama’s rural whites and more than 25 percent of the state’s rural blacks moved into towns or out of the state in search of jobs and entrepreneurial opportunities. Alabama’s urban population grew by 57 percent during the war years. Even though wartime production began tapering off in 1944, by the end of World War II industrial and commercial jobs in the state had increased by 46 percent.

Recruitment Poster

The war produced enormous demographic changes in Alabama. Lured by the prospect of better paying jobs, thousands of Alabamians and workers from nearby states flocked into boom towns such as Mobile, Montgomery, and Huntsville. Approximately 10 percent of Alabama’s rural whites and more than 25 percent of the state’s rural blacks moved into towns or out of the state in search of jobs and entrepreneurial opportunities. Alabama’s urban population grew by 57 percent during the war years. Even though wartime production began tapering off in 1944, by the end of World War II industrial and commercial jobs in the state had increased by 46 percent.

The greatest increase in urban growth occurred in Mobile, where some 90,000 people surged into the city in search of employment. Brookley Field and Mobile’s two shipyards—Gulf Shipbuilding and Alabama Dry Dock and Shipbuilding (ADDSCO)—employed 60,000 workers at their peak. Thousands of merchant seamen sailed on ships operated by the Waterman Steamship Company and Alcoa. The port of Mobile, anchored by the Alabama State Docks, was the nation’s 15th busiest port. Mobile’s wartime population explosion severely strained the area’s infrastructure. Only San Diego, California, and the Norfolk, Virginia, area experienced comparable wartime urban stresses.

Redstone Ordnance Plant

Elsewhere in Alabama, 20,000 workers flocked into the Coosa Valley to build a gunpowder plant in Childersburg—a town with only 500 residents and no paved streets—and an artillery powder bagging plant in nearby Talladega. The construction of two arsenals in Huntsville transformed the peaceful county seat of 13,000 residents into a major center of ordnance production. At the height of wartime production, the Redstone Ordnance Plant, which manufactured conventional explosives, and the Huntsville Arsenal, which manufactured chemical and incendiary ordnance, employed 11,000 civilian workers. Demand for steel led Birmingham’s Tennessee Coal and Iron (TCI) to increase its workforce from 7,000 in 1939 to 30,000 two years later. Other Birmingham companies ramped up production to meet wartime needs as well.

Redstone Ordnance Plant

Elsewhere in Alabama, 20,000 workers flocked into the Coosa Valley to build a gunpowder plant in Childersburg—a town with only 500 residents and no paved streets—and an artillery powder bagging plant in nearby Talladega. The construction of two arsenals in Huntsville transformed the peaceful county seat of 13,000 residents into a major center of ordnance production. At the height of wartime production, the Redstone Ordnance Plant, which manufactured conventional explosives, and the Huntsville Arsenal, which manufactured chemical and incendiary ordnance, employed 11,000 civilian workers. Demand for steel led Birmingham’s Tennessee Coal and Iron (TCI) to increase its workforce from 7,000 in 1939 to 30,000 two years later. Other Birmingham companies ramped up production to meet wartime needs as well.

The war also benefited agriculture. Cotton prices, stagnant throughout the Depression, rose as textile mills won contracts to produce uniforms, bedding, tents, and sandbags. Alabama’s forest-products industry, aided by increased demand for lumber and paper products, ranked third in the nation. Labor shortages plagued agriculture during the war. Some farmers experimented with mechanization, but the scarcity of metal for civilian use postponed the tractor revolution until after the war. In some areas, farmers relied on Axis prisoners of war to chop cotton, harvest crops, and fell timber. The mobilization of nearly 4,000 POWs saved Alabama’s $38 million peanut crop in 1944.

World War II Welder

With approximately one-third of Alabama’s draft-eligible men in uniform, defense industries across the United States launched drives to recruit women. At the height of war production in 1943–44, women comprised about one-fourth of the labor force in Alabama’s defense industries. Women who had once taught in public schools for $800 annually found jobs as assembly-line workers in the Huntsville or Redstone arsenals for $1,400 or as welders in the Mobile shipyards for $3,600. Long excluded from the ranks of skilled and semi-skilled laborers, some African American men found increased opportunities in industry. More than 20 percent of the workers at the Huntsville Arsenal were African American, including a significant number of African American women.

World War II Welder

With approximately one-third of Alabama’s draft-eligible men in uniform, defense industries across the United States launched drives to recruit women. At the height of war production in 1943–44, women comprised about one-fourth of the labor force in Alabama’s defense industries. Women who had once taught in public schools for $800 annually found jobs as assembly-line workers in the Huntsville or Redstone arsenals for $1,400 or as welders in the Mobile shipyards for $3,600. Long excluded from the ranks of skilled and semi-skilled laborers, some African American men found increased opportunities in industry. More than 20 percent of the workers at the Huntsville Arsenal were African American, including a significant number of African American women.

Alabama at War’s End

By 1944 war’s end was in sight. Defense plants and shipyards began scaling back production. On D-Day, June 6, 1944, the Allies established a beachhead on France’s Normandy coast, and in less than a year Germany had surrendered. Grateful for Germany’s defeat but mindful of the continuing war in the Pacific, Alabamians celebrated VE (Victory in Europe) Day somberly. Fearing massive Allied casualties in a conventional invasion of Japan, Pres. Harry Truman, having succeeded Roosevelt after his death in April 1945, ordered atomic bombs dropped on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. On August 15, Emperor Hirohito announced Japan’s surrender. Two weeks later, a flotilla of Allied warships, including the battleship USS Alabama, sailed into Tokyo Bay for formal surrender ceremonies.

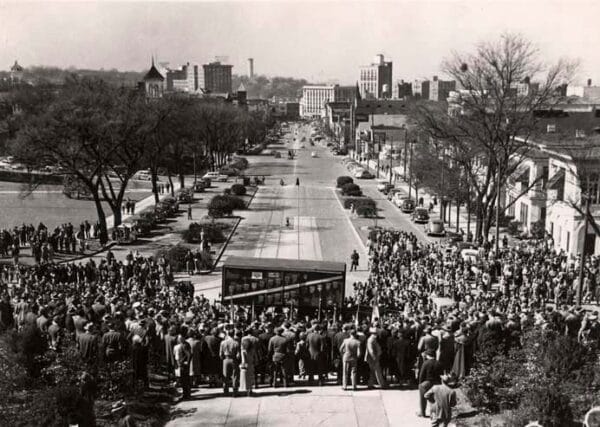

“Merci Train” Car in Montgomery, 1949

World War II and its aftermath had a profound impact on Alabama and the nation. For many veterans, the most significant—and democratizing—benefit of military service was the GI Bill of Rights of 1944, which provided greater access to college and vocational education, home ownership, and health care. Some veterans brought home to Alabama women that they married or met elsewhere. These wartime and post-war marriages produced an unprecedented “baby boom.”

“Merci Train” Car in Montgomery, 1949

World War II and its aftermath had a profound impact on Alabama and the nation. For many veterans, the most significant—and democratizing—benefit of military service was the GI Bill of Rights of 1944, which provided greater access to college and vocational education, home ownership, and health care. Some veterans brought home to Alabama women that they married or met elsewhere. These wartime and post-war marriages produced an unprecedented “baby boom.”

Fought to defend democracy and freedom, the war served as an incubator for the modern civil-rights and women’s movements, as women and African Americans were forced to give up jobs to returning veterans. In Alabama, these changes, combined with the expanding power of the federal government, gave rise to the postwar Dixiecrat movement and its inflammatory racial politics of the 1960s and 1970s. The military bases that were established or expanded during the war provided a significant boost to Alabama’s economy, and many continue to do so in the present. The technological developments associated with the war industry positioned Alabama to become a leader in the aerospace industry, which it remains today.

Further Reading

- Cronenberg, Allen. Forth to the Mighty Conflict: Alabama and World War II. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1995.

- Jakeman, Robert J. The Divided Skies: Establishing Segregated Flight Training at Tuskegee, Alabama, 1934-1942. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1992.

- Newton, Wesley Phillips. Montgomery in the Good War: Portrait of a Southern City, 1940–1946. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2000.

- Noles, Jim. Camp Rucker during World War II. Charleston, S.C.: Arcadia, 2002.

- Rickman, Sarah Byrn. “Nancy Batson, Pursuit Pilot Extraordinaire.” Alabama Heritage 65 (Summer 2002): 14-23.

- Scott, Jr., John B. “The Crommelin Brothers.” Alabama Heritage 46 (Fall 1997): 6-17

- Sledge, Eugene B. With the Old Breed at Peleliu and Okinawa. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990.

- Thomas, Mary Martha. Riveting and Rationing in Dixie: Alabama Women and the Second World War. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1987.