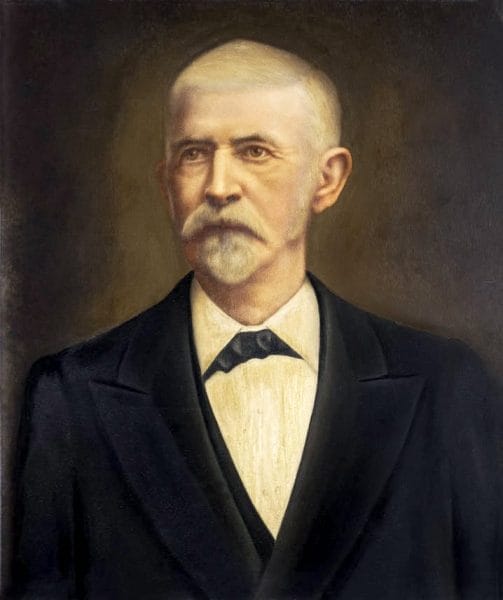

George Washington Stone

Stone, George Washington

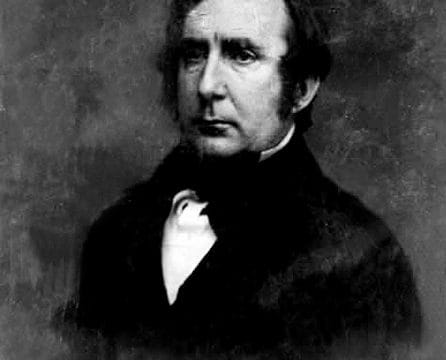

George Washington Stone (1811-1894) was renowned in the judicial history of Alabama for his diligence and his devotion to a career that spanned five decades. In his 28 years on the Alabama Supreme Court, he wrote more than 2,400 opinions extending through 60 volumes of the official reports of the court. Stone’s reputation was built on the quality of his decisions, especially those limiting the use of self-defense in murder cases, and on the role he played in professionalizing the practice of law in Alabama.

Stone, George Washington

George Washington Stone (1811-1894) was renowned in the judicial history of Alabama for his diligence and his devotion to a career that spanned five decades. In his 28 years on the Alabama Supreme Court, he wrote more than 2,400 opinions extending through 60 volumes of the official reports of the court. Stone’s reputation was built on the quality of his decisions, especially those limiting the use of self-defense in murder cases, and on the role he played in professionalizing the practice of law in Alabama.

George Washington Stone was born on October 24, 1811, in Bedford County, Virginia, one of three children of Micajah and Sarah Leftwich Stone. The family moved to Lincoln County, Tennessee, in 1817, where Stone received the limited education offered by local academies. His father died when Stone was 16, and he used his small inheritance to study law under James Fulton of Fayetteville, Tennessee.

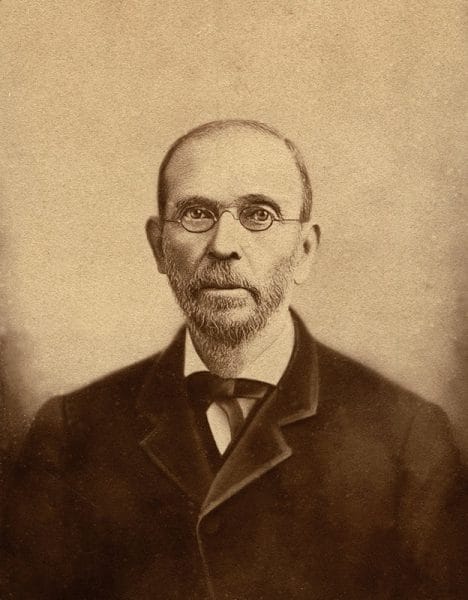

Benjamin Fitzpatrick

In 1834, Stone married Mary Gillespie of Franklin, Tennessee, with whom he had one child, Martha. The couple moved that year to Talladega County, and Stone was soon admitted to the Alabama State Bar and opened his first law practice in the community of Cleveland’s Store. Five years later, he was admitted to practice before the Alabama Supreme Court. A firm supporter of Pres. Andrew Jackson, Stone quickly became active in the county’s Democratic Party. In 1843, Gov. Benjamin Fitzpatrick selected Stone to fill an unexpired term on the Ninth Circuit Court. The legislature elected him to a full six-year term later that year, but Stone did not stand for reelection following the death of his wife in 1848. In 1849, Stone relocated to Hayneville in Lowndes County, where he met and married Emily Moore. The couple had four children, two of whom died young from scarlet fever. He formed a partnership with Thomas J. Judge. In 1856, the legislature elected Stone an associate justice of the Supreme Court, and he moved to Montgomery, where as a judge he played no part in resolving the then-critical issues of slavery and secession. After the death of his second wife in 1862, Stone married Mary Harrison Wright in 1866.

Benjamin Fitzpatrick

In 1834, Stone married Mary Gillespie of Franklin, Tennessee, with whom he had one child, Martha. The couple moved that year to Talladega County, and Stone was soon admitted to the Alabama State Bar and opened his first law practice in the community of Cleveland’s Store. Five years later, he was admitted to practice before the Alabama Supreme Court. A firm supporter of Pres. Andrew Jackson, Stone quickly became active in the county’s Democratic Party. In 1843, Gov. Benjamin Fitzpatrick selected Stone to fill an unexpired term on the Ninth Circuit Court. The legislature elected him to a full six-year term later that year, but Stone did not stand for reelection following the death of his wife in 1848. In 1849, Stone relocated to Hayneville in Lowndes County, where he met and married Emily Moore. The couple had four children, two of whom died young from scarlet fever. He formed a partnership with Thomas J. Judge. In 1856, the legislature elected Stone an associate justice of the Supreme Court, and he moved to Montgomery, where as a judge he played no part in resolving the then-critical issues of slavery and secession. After the death of his second wife in 1862, Stone married Mary Harrison Wright in 1866.

During the Civil War, Stone, unlike some Confederate judges, continued to rely on precedents previously set by the U.S. Supreme Court, and that court later cited two of Stone’s wartime decisions in its own opinions. In the first case, ex parte Hill in re Willis v. Confederate States (1864) Stone recognized the need to keep a distinct dividing line between the rights of local and national governments. In State ex reel. Dawson, in re Strawbridge and Mays (1864), Stone ruled that when there was a conflict between state and federal law, national law took precedent. In 1865, Alabama’s provisional governor, Lewis E. Parsons, appointed an entirely new court, and Stone returned to private practice. He also produced The Penal Code of Alabama, a manual of all the state laws at that time.

After Democrats regained control of the legislature from Republicans, Stone was reelected to the Supreme Court to fill a vacancy caused by the death of his former law partner Thomas J. Judge. In 1884, Gov. Edward A. O’Neal appointed Stone Chief Justice, a position he held until his death in 1894, thereby becoming one of the longest-serving justices in Alabama history.

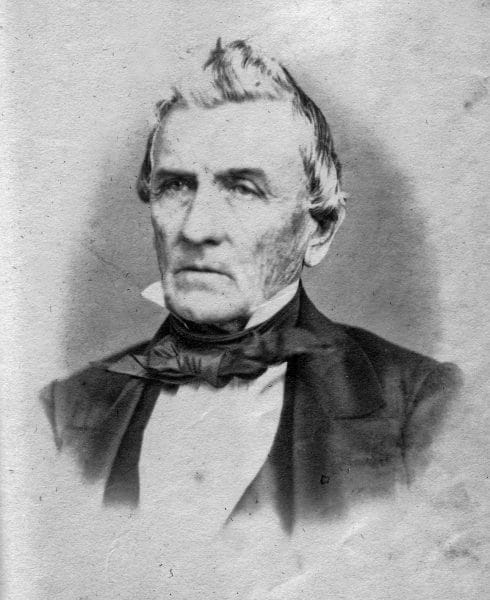

Lewis E. Parsons

After the Civil War, Stone helped develop what one of his contemporaries considered “an excellent body” of corporate law in Alabama. In Perry v. New Orleans, Mobile and Chattanooga Railroad Company (1876), for example, Stone ruled that state legislatures were entitled to use their police power to facilitate projects in the public interest, including railroads. In other cases, he conferred on corporations all the rights of a natural person, and on more than one occasion he struck down state laws that treated railroads or other companies differently from individuals, decisions that facilitated the development of a modern capitalist industrial economy in the state.

Lewis E. Parsons

After the Civil War, Stone helped develop what one of his contemporaries considered “an excellent body” of corporate law in Alabama. In Perry v. New Orleans, Mobile and Chattanooga Railroad Company (1876), for example, Stone ruled that state legislatures were entitled to use their police power to facilitate projects in the public interest, including railroads. In other cases, he conferred on corporations all the rights of a natural person, and on more than one occasion he struck down state laws that treated railroads or other companies differently from individuals, decisions that facilitated the development of a modern capitalist industrial economy in the state.

Stone penned his most influential opinions in a series of cases that restricted the use of self-defense arguments in murder cases. In McManus v. State (1860) he asserted that “an insult, or an assault, or an assault and battery, which does not endanger life or member, furnishes no excuse for taking life.” In Bain v. State (1881), he established unambiguous criteria for justifiable homicide: the defendant must not “provoke or encourage the difficulty”; the defendant must be “so menaced . . . as to create a reasonable apprehension of the loss of his life”; and there must be no “reasonable mode of escape” for the defendant.

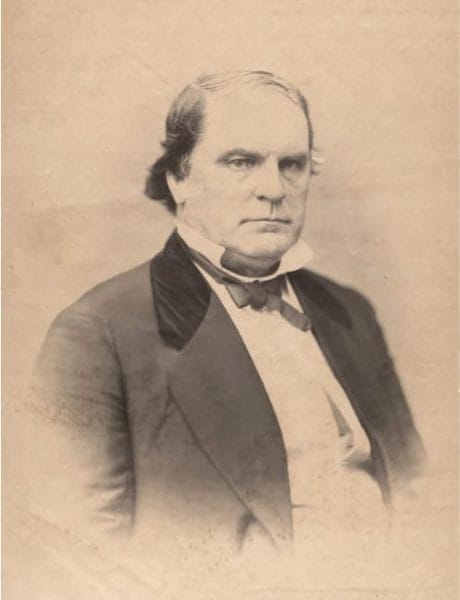

Edward A. O’Neal

In Myers v. State (1878), Stone reiterated his contention that encouraging a fight nullified self-defense, and in Cleveland v. State (1888), he put the “burden on the defendant to show that he had no alternative” to murder. In the next century, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes would cite these opinions in rulings of the U.S. Supreme Court, and they continue to have relevance today. Stone’s scholarly insights in his opinions, along with his own high professional standards, made him a natural leader in the movement to elevate the status of the bench and bar in Alabama. In 1841, he helped organize a bar association in Talladega, where he had just opened a practice. In 1879, he played a central role in organizing the Alabama Bar Association. During his last years on the Supreme Court, he used the association’s annual meetings to advocate for judicial reforms.

Edward A. O’Neal

In Myers v. State (1878), Stone reiterated his contention that encouraging a fight nullified self-defense, and in Cleveland v. State (1888), he put the “burden on the defendant to show that he had no alternative” to murder. In the next century, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes would cite these opinions in rulings of the U.S. Supreme Court, and they continue to have relevance today. Stone’s scholarly insights in his opinions, along with his own high professional standards, made him a natural leader in the movement to elevate the status of the bench and bar in Alabama. In 1841, he helped organize a bar association in Talladega, where he had just opened a practice. In 1879, he played a central role in organizing the Alabama Bar Association. During his last years on the Supreme Court, he used the association’s annual meetings to advocate for judicial reforms.

Outside the courtroom, Stone spent much time with his violin, which he played entirely by ear, to entertain his children and grandchildren. He also enjoyed writing verse, publishing a small volume of his work in 1871, and cultivated an extensive flower garden. Stone died on March 11, 1894, and was buried in Oakwood Cemetery in Montgomery.

Additional Resources

Brantley, William H., Jr. Chief Justice Stone of Alabama. Birmingham, Ala.: Birmingham Publishing, 1943.

Caffey, George. “George Washington Stone, 1811-1894.” In Vol. 6, Great American Lawyers. Philadelphia: John C. Winston, 1907-1909: 165-93.

“Chief Justice George W. Stone.” Alabama Lawyer 31 (1970): 165.

George W. Stone Papers. Alabama Department of Archives and History. Montgomery, Alabama.

Huebner, Timothy S. The Southern Judicial Tradition: State Judges and Sectional Distinctiveness, 1790-1890. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1999.