Clifford Durr

Clifford Durr

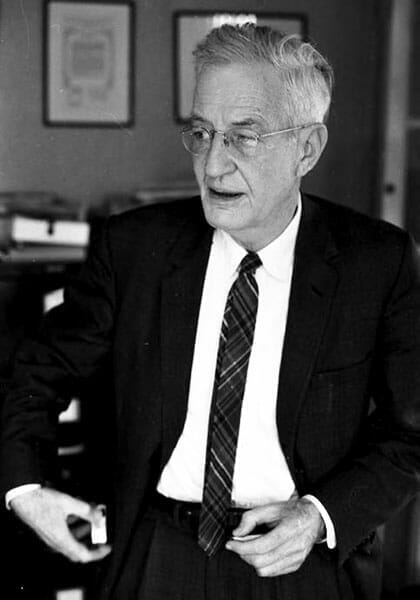

Clifford Durr (1899-1975) was a lawyer and nationally respected defender of civil liberties during the post-World War II Red Scare, a supporter of the civil rights movement, and counsel to civil rights icon Rosa Parks. In his early life, he reflected the race- and class-based attitudes of his Alabama contemporaries, but during the years of the Great Depression and the subsequent New Deal he experienced an intellectual awakening. With the help of his activist wife, Virginia Foster Durr, Clifford Durr defended those unable to defend themselves, often at the expense of his own livelihood.

Clifford Durr

Clifford Durr (1899-1975) was a lawyer and nationally respected defender of civil liberties during the post-World War II Red Scare, a supporter of the civil rights movement, and counsel to civil rights icon Rosa Parks. In his early life, he reflected the race- and class-based attitudes of his Alabama contemporaries, but during the years of the Great Depression and the subsequent New Deal he experienced an intellectual awakening. With the help of his activist wife, Virginia Foster Durr, Clifford Durr defended those unable to defend themselves, often at the expense of his own livelihood.

Clifford Judkins Durr was born on March 2, 1899, to John Wesley Durr and Lucy Judkins Durr, a privileged Montgomery family with deep Alabama roots. His grandfather John Wesley Durr was a Montgomery cotton factor (a business agent for cotton growers) in the years just before the Civil War, and his grandfather James Henry Judkins owned a plantation; both served as captains in the Confederate Army. A few years before Clifford’s birth, his father founded the business that became the Durr Drug Company, and the basis for the family’s comfortable life.

Clifford Durr as a Child

Educated in Montgomery private schools, Durr was elected president of his class at the University of Alabama and later won a Rhodes scholarship to Oxford University in England. He graduated in 1922 from Oxford with a coveted law degree, but he considered his two years there a time of exile from the American South. Upon his return he joined a Montgomery law firm run by family friends. He also practiced law for a year in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. After passing both the Wisconsin and Alabama State Bar exams, he accepted a position with the Birmingham corporate-law firm of Martin, Thompson, Foster, and Turner, which opened doors for him into Alabama’s legal establishment. Steady, scholarly, good looking, and well-liked, Durr enjoyed his work and was poised for a successful legal career.

Clifford Durr as a Child

Educated in Montgomery private schools, Durr was elected president of his class at the University of Alabama and later won a Rhodes scholarship to Oxford University in England. He graduated in 1922 from Oxford with a coveted law degree, but he considered his two years there a time of exile from the American South. Upon his return he joined a Montgomery law firm run by family friends. He also practiced law for a year in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. After passing both the Wisconsin and Alabama State Bar exams, he accepted a position with the Birmingham corporate-law firm of Martin, Thompson, Foster, and Turner, which opened doors for him into Alabama’s legal establishment. Steady, scholarly, good looking, and well-liked, Durr enjoyed his work and was poised for a successful legal career.

In 1926 Durr married Virginia Foster, the well-educated daughter of a Birmingham Presbyterian minister of patrician descent who had lost his pulpit in a doctrinal dispute. Her family lived in what she called “genteel poverty,” a designation she later distinguished from the real poverty she saw or understood for the first time in Depression-era Birmingham. The Durrs’ had four daughters and a son who died at age three.

Clifford Durr

Durr accepted a legal job in Washington, D.C., with the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) in 1933, at the beginning of Pres. Franklin D. Roosevelt’s first term. Alabama senator and future Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black, who was married to Virginia’s sister, Josephine Foster, recommended his brother-in-law Durr for the position in the New Deal agency. For the next 17 years, the Durrs lived in Alexandria, Virginia, a suburb of Washington, where they developed lasting and intellectually challenging friendships with social reformers from the South and other parts of the country. Durr served as a productive and innovative lawyer for the RFC for seven years, and when that position ended, he was appointed a member of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC). There, Durr gradually began focusing his work on protecting the public interest rather than advocating for corporate banking or broadcasting interests. At the FCC he fought for advertisement-free public broadcasting and open public-access channels for community participation in the newly emerging television industry.

Clifford Durr

Durr accepted a legal job in Washington, D.C., with the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) in 1933, at the beginning of Pres. Franklin D. Roosevelt’s first term. Alabama senator and future Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black, who was married to Virginia’s sister, Josephine Foster, recommended his brother-in-law Durr for the position in the New Deal agency. For the next 17 years, the Durrs lived in Alexandria, Virginia, a suburb of Washington, where they developed lasting and intellectually challenging friendships with social reformers from the South and other parts of the country. Durr served as a productive and innovative lawyer for the RFC for seven years, and when that position ended, he was appointed a member of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC). There, Durr gradually began focusing his work on protecting the public interest rather than advocating for corporate banking or broadcasting interests. At the FCC he fought for advertisement-free public broadcasting and open public-access channels for community participation in the newly emerging television industry.

Virginia Foster Durr

During Durr’s last two years at the FCC, he became embroiled in conflicts among the agency, the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) regarding civil-liberties issues. He resigned in 1948 in protest of President Harry Truman’s Federal Loyalty Oath Order, which he saw as abusive of FCC employee rights. That year, Virginia Durr ran for the Senate from Virginia representing the short-lived, very liberal Progressive Party, which nominated their friend, former Vice President and Secretary of Commerce Henry Wallace, for the presidency. Despite his disagreements with Truman’s policies, Clifford Durr stayed a loyal Democrat during the conflict-ridden campaign of 1948. The Durrs remained in the Washington area for two more years, and Clifford established a private law practice that focused almost exclusively on civil-liberties cases, which gained the attention of the FBI, and intermittent surveillance by the agency. FBI interest increased when Durr became president of the left-liberal National Lawyers Guild in 1949. The Durrs left Washington and spent a few unhappy months in Denver, Colorado, where Durr headed the National Farmers Union, then returned to Alabama in 1951.

Virginia Foster Durr

During Durr’s last two years at the FCC, he became embroiled in conflicts among the agency, the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) regarding civil-liberties issues. He resigned in 1948 in protest of President Harry Truman’s Federal Loyalty Oath Order, which he saw as abusive of FCC employee rights. That year, Virginia Durr ran for the Senate from Virginia representing the short-lived, very liberal Progressive Party, which nominated their friend, former Vice President and Secretary of Commerce Henry Wallace, for the presidency. Despite his disagreements with Truman’s policies, Clifford Durr stayed a loyal Democrat during the conflict-ridden campaign of 1948. The Durrs remained in the Washington area for two more years, and Clifford established a private law practice that focused almost exclusively on civil-liberties cases, which gained the attention of the FBI, and intermittent surveillance by the agency. FBI interest increased when Durr became president of the left-liberal National Lawyers Guild in 1949. The Durrs left Washington and spent a few unhappy months in Denver, Colorado, where Durr headed the National Farmers Union, then returned to Alabama in 1951.

Clifford Durr at an FCC Hearing

Durr was devoted to his home state, and despite ill health and other obstacles, he made every effort to establish a general law practice in Montgomery in the early 1950s. Most of his clients dropped away in 1954 after the Senate Subcommittee on Internal Security, headed by Mississippi’s arch-segregationist senator James O. Eastland, called Virginia Foster Durr to New Orleans, Louisiana, to testify in highly publicized hearings on the allegedly subversive and decidedly integrationist Southern Conference Education Fund (SCEF). The publicity would affect Cliff Durr’s law practice, but the couple’s very close personal relationship and the similarity of their political views guaranteed his active presence at these threatening and frightening hearings. As a liberal member of the Women’s Committee of the Democratic Party and chair of the anti-poll tax committee of the Southern Conference for Human Welfare, a broader organization that preceded SCEF but had folded in the late 1940s, Virginia Durr had already made an enemy of Eastland. Clifford Durr appeared as counsel for his good friend Aubrey Williams, a resident of Montgomery, president of SCEF, and publisher of the magazine of the National Farmer’s Union, and he gained unfortunate notoriety when he threw a punch at the government’s star anti-communist witness, who lied about Virginia on the stand. Texas senator Lyndon Johnson, a friend from the Washington years, helped quell further harassment by Senator Eastland and his committee, but all hope for Durr’s law practice representing Montgomery businesses died in New Orleans.

Clifford Durr at an FCC Hearing

Durr was devoted to his home state, and despite ill health and other obstacles, he made every effort to establish a general law practice in Montgomery in the early 1950s. Most of his clients dropped away in 1954 after the Senate Subcommittee on Internal Security, headed by Mississippi’s arch-segregationist senator James O. Eastland, called Virginia Foster Durr to New Orleans, Louisiana, to testify in highly publicized hearings on the allegedly subversive and decidedly integrationist Southern Conference Education Fund (SCEF). The publicity would affect Cliff Durr’s law practice, but the couple’s very close personal relationship and the similarity of their political views guaranteed his active presence at these threatening and frightening hearings. As a liberal member of the Women’s Committee of the Democratic Party and chair of the anti-poll tax committee of the Southern Conference for Human Welfare, a broader organization that preceded SCEF but had folded in the late 1940s, Virginia Durr had already made an enemy of Eastland. Clifford Durr appeared as counsel for his good friend Aubrey Williams, a resident of Montgomery, president of SCEF, and publisher of the magazine of the National Farmer’s Union, and he gained unfortunate notoriety when he threw a punch at the government’s star anti-communist witness, who lied about Virginia on the stand. Texas senator Lyndon Johnson, a friend from the Washington years, helped quell further harassment by Senator Eastland and his committee, but all hope for Durr’s law practice representing Montgomery businesses died in New Orleans.

Durr with Hugo Black and Carl Elliott

After the Eastland hearings, Durr often defended black Montgomerians in civil rights cases that mirrored, in his mind, the civil liberties cases of the professional men and women he had defended in Washington. These new clients, however, could seldom pay for his services. In December 1955, he aided Rosa Parks in posting bail on the night of her arrest for refusing to give up her seat in the white section of a Montgomery public bus. He then assisted Fred Gray, a young African American attorney for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), in fashioning Parks’s appeal. Throughout the height of the civil rights era, he defended clients protesting police brutality or wrongful prosecution. One lengthy federal case finally vindicated a mostly white student group arrested while dining in a black Montgomery restaurant. Clifford opened his law library, and Virginia opened their home, to new civil rights lawyers needing assistance and to civil rights workers drawn to Montgomery. Because the Durrs had made fast friends among liberal philanthropists during their Washington years, they received financial support that enhanced Durr’s ability to aid both his clients and movement volunteers. The Durrs remained barely afloat financially, despite this outside assistance, and federal and state agencies kept them under surveillance until 1965, a year after he closed his law practice. In 1969, the Durrs moved to “Pea Level,” a farm in Wetumpka that they had inherited from the Judkins family.

Durr with Hugo Black and Carl Elliott

After the Eastland hearings, Durr often defended black Montgomerians in civil rights cases that mirrored, in his mind, the civil liberties cases of the professional men and women he had defended in Washington. These new clients, however, could seldom pay for his services. In December 1955, he aided Rosa Parks in posting bail on the night of her arrest for refusing to give up her seat in the white section of a Montgomery public bus. He then assisted Fred Gray, a young African American attorney for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), in fashioning Parks’s appeal. Throughout the height of the civil rights era, he defended clients protesting police brutality or wrongful prosecution. One lengthy federal case finally vindicated a mostly white student group arrested while dining in a black Montgomery restaurant. Clifford opened his law library, and Virginia opened their home, to new civil rights lawyers needing assistance and to civil rights workers drawn to Montgomery. Because the Durrs had made fast friends among liberal philanthropists during their Washington years, they received financial support that enhanced Durr’s ability to aid both his clients and movement volunteers. The Durrs remained barely afloat financially, despite this outside assistance, and federal and state agencies kept them under surveillance until 1965, a year after he closed his law practice. In 1969, the Durrs moved to “Pea Level,” a farm in Wetumpka that they had inherited from the Judkins family.

Clifford and Virginia Durr

Durr’s civil rights work brought him accolades and invitations to speak at prestigious American universities and at Oxford in his final years. He received awards from the Southern Regional Council and the New York Civil Liberties Union. An editorial in The Nation, entitled “The Conscience of a Lawyer,” lauded his professional skill and his inclination to conduct himself honorably no matter how difficult the situation. Clifford Durr died on May 12, 1975, and several memorial services honored him, including a large gathering in Washington, D.C. Eulogists praised him as an honest and principled lawyer and public servant, and as a devout man who worked tirelessly to support the Bill of Rights, his country, and his family. Both Clifford and Virginia Foster Durr are buried in Montgomery’s Greenwood Cemetery.

Clifford and Virginia Durr

Durr’s civil rights work brought him accolades and invitations to speak at prestigious American universities and at Oxford in his final years. He received awards from the Southern Regional Council and the New York Civil Liberties Union. An editorial in The Nation, entitled “The Conscience of a Lawyer,” lauded his professional skill and his inclination to conduct himself honorably no matter how difficult the situation. Clifford Durr died on May 12, 1975, and several memorial services honored him, including a large gathering in Washington, D.C. Eulogists praised him as an honest and principled lawyer and public servant, and as a devout man who worked tirelessly to support the Bill of Rights, his country, and his family. Both Clifford and Virginia Foster Durr are buried in Montgomery’s Greenwood Cemetery.

Additional Resources

Alabama Department of Archives and History, Montgomery: Clifford Judkins Durr Papers, LPR No. 25; Virginia Foster Durr Papers, LPR No. 28.

Barnard, Hollinger F., ed. Outside the Magic Circle: The Autobiography of Virginia Foster Durr. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1985.

Brown, Sarah Hart. Standing Against Dragons: Three Southern Lawyers in an Era of Fear. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1998.

Salmon, John A. The Conscience of a Lawyer: Clifford J. Durr and American Civil Liberties, 1899-1975. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1990.

Sullivan, Patricia. Freedom Writer: Virginia Foster Durr, Letters from the Civil Rights Years. Routledge, 2003.