Willie Mays

Mays, Willi

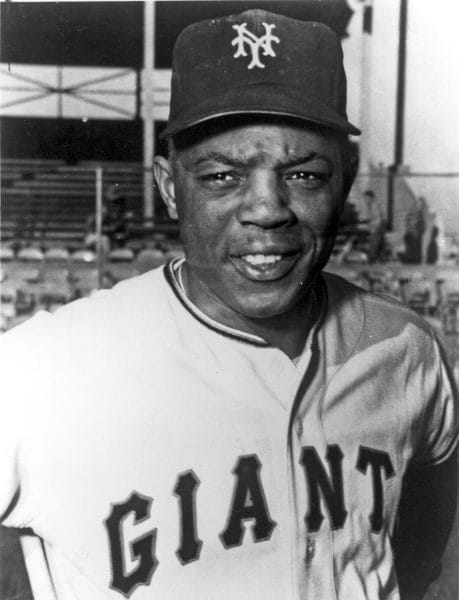

Willie Mays (1931- ) is one of the greatest baseball players to ever play the game. Only his excellence at hitting, hitting for power, running, fielding, and throwing exceeded his love for the game. In 22 major league seasons (1951, 1954–73), mostly with the New York, and later, San Francisco Giants, Mays had a .302 lifetime batting average, amassed 3,283 hits, 660 home runs, 1,903 runs batted in, 2,062 runs, 338 steals, and an untouchable total of 7,095 career putouts from outfield. Affectionately known as the “Say Hey Kid,” Mays was the National League Rookie of the Year in 1951, played a significant role in the New York Giants World Series victory in 1954, and earned most-valuable-player (MVP) awards in 1954 and 1965. In addition, he was awarded 12 Gold Glove awards for his fielding, honored with 24 All-Star Game appearances, won a National League batting title in 1954 with a .345 batting average, and was a first-ballot Hall of Fame inductee in 1979, only the ninth person so far paid that honor.

Mays, Willi

Willie Mays (1931- ) is one of the greatest baseball players to ever play the game. Only his excellence at hitting, hitting for power, running, fielding, and throwing exceeded his love for the game. In 22 major league seasons (1951, 1954–73), mostly with the New York, and later, San Francisco Giants, Mays had a .302 lifetime batting average, amassed 3,283 hits, 660 home runs, 1,903 runs batted in, 2,062 runs, 338 steals, and an untouchable total of 7,095 career putouts from outfield. Affectionately known as the “Say Hey Kid,” Mays was the National League Rookie of the Year in 1951, played a significant role in the New York Giants World Series victory in 1954, and earned most-valuable-player (MVP) awards in 1954 and 1965. In addition, he was awarded 12 Gold Glove awards for his fielding, honored with 24 All-Star Game appearances, won a National League batting title in 1954 with a .345 batting average, and was a first-ballot Hall of Fame inductee in 1979, only the ninth person so far paid that honor.

Willie Howard Mays Jr. was born in Westfield, Jefferson County, on May 6, 1931, and raised in nearby Fairfield, a steel-mill town on the outskirts of Birmingham, the offspring of two athletic stars. His father, Willie “Cat” Mays Sr., had been a Negro League player, and his mother Annie had been a champion sprinter in high school. From the time Mays was a toddler, he was an athletic prodigy. Known as “Buck,” by family and friends, Mays exhibited athletic brilliance when he was 10, as a bat boy who played first base in the final two innings of sandlot games in the Birmingham Industrial League for the Fairfield Stars. Mays lacked the size to be a power hitter in his early teens, but he did display extraordinary skills in running, fielding, and throwing—skills for which Mays is best remembered by major league fans. At the all-black Fairfield Industrial High School, Mays was also a star quarterback and basketball player but concentrated his talents on baseball.

With the Fairfield Stars, Mays quickly made the starting lineup as shortstop before moving up to professional baseball in 1946, as a 15-year-old outfielder briefly playing for the New York Cubans. In 1947, Mays also temporarily played for the Chattanooga Choo Choos, before joining the Negro Leagues’ Birmingham Black Barons on a more permanent basis. With the Barons, Mays made $250 a month to play on a part-time basis, so that he could attend and graduate from high school. While in high school, Mays played professional baseball on weekends and attended classes during the week. In 1947, Jackie Robinson brought hope to all black athletes by breaking Major League Baseball’s color barrier, signing with the Brooklyn Dodgers.

Mays, Willie

Like Robinson, Mays encountered segregation and racism. He received much-needed guidance from his father and his uncle, as well as from Black Barons manager Pepper Davis, who made sure Mays stayed focused on baseball while he matured as a player. Davis’s guidance was especially helpful with Mays’s hitting, and Davis taught him to be patient as he was learning to hit curveball, slider, and changeup pitches. In 1949 his batting average with the Black Barons rose to a solid .311 and rose again the following year to .330. This marked improvement impressed major-league scouts and led to a $15,000-a-year contract with the New York Giants after Mays graduated from high school in 1950. The offer was unexpected because the Giants originally had been interested not in Mays but in his teammate Alonzo Perry. Before becoming a fixture with the Giants, Mays excelled in the minor leagues for two years. In 1950, he played Class B ball for Trenton, New Jersey, batting .353 in 81 games, before being promoted to Class AAA ball and the Minneapolis Millers. In 1951, Mays’s hitting reached .477 in 35 AAA games. He was quickly called up to the Giants.

Mays, Willie

Like Robinson, Mays encountered segregation and racism. He received much-needed guidance from his father and his uncle, as well as from Black Barons manager Pepper Davis, who made sure Mays stayed focused on baseball while he matured as a player. Davis’s guidance was especially helpful with Mays’s hitting, and Davis taught him to be patient as he was learning to hit curveball, slider, and changeup pitches. In 1949 his batting average with the Black Barons rose to a solid .311 and rose again the following year to .330. This marked improvement impressed major-league scouts and led to a $15,000-a-year contract with the New York Giants after Mays graduated from high school in 1950. The offer was unexpected because the Giants originally had been interested not in Mays but in his teammate Alonzo Perry. Before becoming a fixture with the Giants, Mays excelled in the minor leagues for two years. In 1950, he played Class B ball for Trenton, New Jersey, batting .353 in 81 games, before being promoted to Class AAA ball and the Minneapolis Millers. In 1951, Mays’s hitting reached .477 in 35 AAA games. He was quickly called up to the Giants.

Mays’s major league debut came on May 25, 1951, and began with a rocky start. In his first seven games he had one hit in 26 at-bats, a .036 batting average, which had the uncertain 22-year-old prodigy in tears and wondering if he was going to last longer than a week. After receiving reassurances from Giants manager Leo Durocher that Mays was his center fielder, Mays blossomed into the “Say Hey Kid.” The nickname was allegedly given to Mays that year by New York Journal American sportswriter Barney Kremenko, after he heard Mays utter “‘Say who,’ ‘Say what,’ ‘Say where,’ ‘Say hey,'” in reference to him not knowing his teammates’ names when he first joined the Giants. Even during his hitting slump, Mays displayed brilliance as a fielder. His batting quickly matured, however, and he soon had an average of .274, with 20 home runs and 68 RBIs in 121 games. In 1951 he was named the National League’s Rookie of the Year and led the Giants in a miraculous come-from-behind National League pennant win over the rival Brooklyn Dodgers.

In 1952 Mays was drafted into the U.S. Army to serve during the Korean War. He never saw combat and continued to hone his baseball skills playing at Fort Eustis in Newport News, Virginia. Although Mays estimated that he lost 70 to 80 home runs during his two-year stint in the Army, he was a player who managed himself into a great hitter.

Mays’s return to the Giants in 1954 was eagerly anticipated and did not disappoint the fans. He led the National League with a .345 batting average, 41 home runs, 110 RBIs, 13 triples, and scored 119 runs on his way to becoming the Most Valuable Player and leading the Giants to a World Series title over the favored Cleveland Indians. The most memorable moment in Mays’ career occurred in the first game of the series, when he made a running, over-the-shoulder catch at the warning track off of a long hit by Vic Wertz. Popularly known as “The Catch,” Mays spoke of the play as “The Throw.” He believed the catch was routine, but the immediate stop and U-turn throw in a tied eighth inning, with runners on first and second, allowed only one runner to advance without scoring. The play was the key to the Giants winning the game and sweeping the Series.

In New York, Mays was loved by New Yorkers on a scale comparable to that bestowed on New York Yankee Mickey Mantle and Brooklyn Dodger Duke Snider. After the Giants moved to San Francisco in 1958, his popularity was never the same as it was in New York, even though Mays’s play continued to transcend mere statistics. In 1962 Mays led the Giants to another pennant victory, and in 1964 he became the first black team captain in the major leagues and won his second MVP award. In 1966, at age 35, he became the highest-paid player in baseball history and hit 37 home runs. After that year, however, Mays’ level of play began to decline. Thereafter he hit no more than 28 home runs in a season and had only 118 home runs combined in his final seven seasons. In spite of those declining numbers, in 1970 Mays was named “Player of the Decade” for the 1960s by the Sporting News. He played his final two seasons in 1972 and 1973 as a part-time first baseman for the New York Mets. He then worked as a part-time hitting coach with the Mets until 1979. He was the first ballplayer with more than 3,000 hits and 500 home runs in his career, an accomplishment subsequently matched only by Hank Aaron, Eddie Murray, and Rafael Palmeiro.

Mays was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York, in 1979, the same year he became embroiled in controversy. In 1979 Mays and Mantle were banned from baseball by Commissioner Bowie Kuhn for working as goodwill ambassadors with Park Place Casino (now Bally’s Casino Resort) in Atlantic City, violating the league’s rules on gambling. In 1985, both men were reinstated by the next commissioner, Peter Ueberroth.

Since 1986 Mays has worked in the lifetime position of Special Assistant to the President of the San Francisco Giants. In recent years, Mays and his jersey number 24 have been immortalized at the Giants’ new stadium, Pacific Bell Park. There, a nine-foot tall bronze statue of Mays presides over the main plaza at the stadium’s address, 24 Willie Mays Plaza, surrounded by 24 palm trees, and the stadium’s right-field wall stands at a height of 24 feet. In July 2013, New York City renamed two uptown streets in Mays’s honor. On November 24, 2015, Pres. Barack Obama awarded Mays a Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian award in the United States.

Additional Resources

Einstein, Charles. Willie’s Time: Baseball’s Golden Age. Carbondale, Ill.: Southern Illinois University Press, 2004.

Hirsch, James. Willie Mays: The Life, The Legend. New York: Scribner, 2010.

Linge, Mary Kay. Willie Mays: A Biography. New York: Greenwood Press, 2005.