Segregation (Jim Crow)

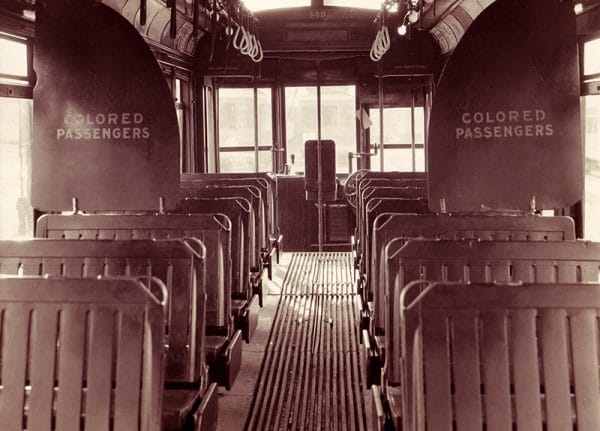

Segregated Birmingham Streetcar

Segregation was the legal and social system of separating citizens on the basis of race. The system maintained the repression of Black citizens in Alabama and other southern states until it was dismantled during the civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s and by subsequent civil rights legislation. Segregation is usually understood as a legal system of control consisting of the denial of voting rights, the maintenance of separate schools, and other forms of separation between the races, but formal legal rules were only one part of the regime. Some historians list three other important elements contributing to the creation and reinforcement of the status quo: physical force and terror, economic intimidation, and psychological control exerted through messages of low worth and negativity transmitted socially to African American citizens.

Segregated Birmingham Streetcar

Segregation was the legal and social system of separating citizens on the basis of race. The system maintained the repression of Black citizens in Alabama and other southern states until it was dismantled during the civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s and by subsequent civil rights legislation. Segregation is usually understood as a legal system of control consisting of the denial of voting rights, the maintenance of separate schools, and other forms of separation between the races, but formal legal rules were only one part of the regime. Some historians list three other important elements contributing to the creation and reinforcement of the status quo: physical force and terror, economic intimidation, and psychological control exerted through messages of low worth and negativity transmitted socially to African American citizens.

The Rise of Legal Segregation

As a comprehensive legal and social policy, segregation was not fully institutionalized in Alabama until the beginning of the twentieth century but had its roots in struggles over how to deal with the realities of emancipation and federal legislation and constitutional change that gave Blacks full citizenship. While many Alabamians informally and incompletely enforced separate living and working arrangements during slavery, the state’s role in formalizing and codifying separation was a postwar development. Formal and informal policies of repression, such as separate public accommodations, limited access to suffrage, and strict control over Black labor, were put into place between the 1870s and the 1890s, and Alabama’s 1901 Constitution rested upon white supremacy as a basic element of governance. The supremacist underpinnings of the constitution persisted until judicial decisions in the 1950s and 1960s rendered them inoperable, and some segregationist language, like the ban on interracial marriage, remained in the constitution until Alabama’s voters removed it by constitutional amendment in the twenty-first century.

At the end of the Civil War, Alabama had to reconstitute its state legislature. The state’s first postwar constitution, drafted in 1865, actually cut back on equal rights for freedmen that had been present in Alabama’s previous constitutions. For instance, the new political order limited free Blacks’ capacity to make choices about labor contracts and heavily promoted formal marriages between free Blacks while prohibiting interracial marriage. Rather than guaranteeing equal rights in the constitution, the drafters instructed the legislature to “pass such laws as will protect the freedmen of this state in the full enjoyment of all their rights of person and property, and guard them and the state against all evil that may arise from their sudden emancipation.” While the drafters promoted protection for freed slaves, they suggested to the legislature that the best form of protection for both the freed slaves and the state would be the development of a new form of second-class status and citizenship. The legislature reconvened in December 1865 and responded by passing Alabama’s notorious Black Code, which, like those passed in other states, rigidly controlled and managed the lives of Black citizens. Although the codes primarily focused upon compelling Blacks to labor for whites (often their former masters) and punishing them harshly for vaguely defined crimes like loitering and vagrancy, they foreshadowed the social and geographic control that full-scale segregation would bring.

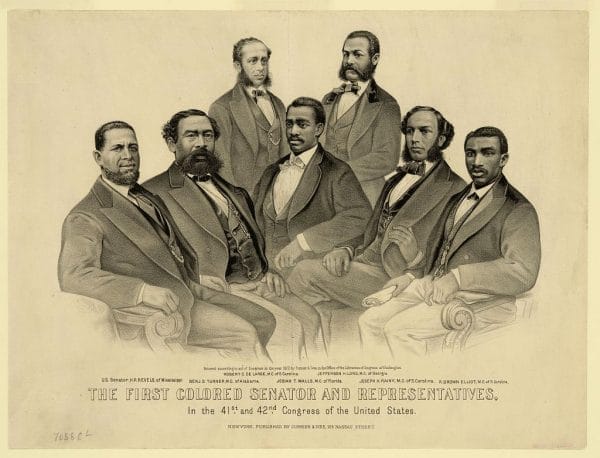

Black Legislators Elected During Reconstruction

The harshness of the codes in conjunction with remaining northern bitterness about the war contributed to major Republican victories in national elections in 1866. Federal officials suspended the codes in all southern states, and in Alabama and elsewhere a new wave of constitution writing began. Alabama’s 1867 constitutional convention included 18 African Americans who spoke against the discriminatory constitutional and statutory language in the existing legal system. In Alabama, the convention voted against mandating segregated schooling in its constitution, leading 13 pro-segregation delegates to resign from their positions. Alabama’s 1868 constitution included an equal-protection guarantee and also secured suffrage rights for men over 21 regardless of race, but it did little else to provide formal legal protection for African Americans. Even these fairly modest reforms provoked outrage among many Democrats and conservatives, and the broader politics of Reconstruction contributed to the formation of the Ku Klux Klan, especially in Alabama, a center of Klan activity during Reconstruction. Klan violence was not random. Klansmen directly targeted African Americans and their white allies who sought to enforce guarantees of equal political and social rights.

Black Legislators Elected During Reconstruction

The harshness of the codes in conjunction with remaining northern bitterness about the war contributed to major Republican victories in national elections in 1866. Federal officials suspended the codes in all southern states, and in Alabama and elsewhere a new wave of constitution writing began. Alabama’s 1867 constitutional convention included 18 African Americans who spoke against the discriminatory constitutional and statutory language in the existing legal system. In Alabama, the convention voted against mandating segregated schooling in its constitution, leading 13 pro-segregation delegates to resign from their positions. Alabama’s 1868 constitution included an equal-protection guarantee and also secured suffrage rights for men over 21 regardless of race, but it did little else to provide formal legal protection for African Americans. Even these fairly modest reforms provoked outrage among many Democrats and conservatives, and the broader politics of Reconstruction contributed to the formation of the Ku Klux Klan, especially in Alabama, a center of Klan activity during Reconstruction. Klan violence was not random. Klansmen directly targeted African Americans and their white allies who sought to enforce guarantees of equal political and social rights.

The Democrats regained tenuous control of Alabama’s government in 1874, and they continued to fend off challenges from Republicans and emerging third parties intermittently through the 1870s and 1880s. By the end of the 1880s, the unification of Democrats around an agenda of racial hostility toward Blacks had contributed to dividing and weakening the Republican Party. Black and white Republicans were holding separate conventions as white Republicans sought to distance themselves from the appearance of advocating for freed men and women. Alabama held another constitutional convention in 1875, but the delegates did little to weaken the language forbidding racial discrimination in voting, because they did not wish to trigger federal intervention.

As these constitutional changes were occurring and Congress and the U.S. Supreme Court were struggling over the legacy of emancipation, southern states and localities quietly began to implement the first building blocks of segregation. Railway cars were an early target, and in the late 1870s and 1880s, trains began to shift from reserving cars for ladies to reserving cars for white passengers. As these practices became more widespread, many southern states and localities, including Alabama and its major cities, passed laws and ordinances mandating racial segregation on trains passing through them and on city streetcars. Policies criminalizing interracial marriage, and in Alabama other forms of interracial intimacy, were initially challenged on the basis of federal law and the Fourteenth Amendment, which provided freedmen with basic citizenship rights. But state courts and then the U.S. Supreme Court, in the 1883 case Pace v. Alabama, indicated that such laws were permissible. Legal challenges to segregated transportation increased, and African Americans sought to enforce their legal rights under congressional legislation. The federal government, however, began to lose its will to enforce equality. Finally, in 1896 the U.S. Supreme Court considered the case of Plessy v. Ferguson, in which mixed-race plaintiff Homer Plessy challenged Louisiana’s 1890 law mandating separate accommodations for Black and white passengers in railway cars. The court ruled that Louisiana’s law was constitutional and established the principle that separate accommodations were acceptable as long as they were equal. This ruling granted wide latitude to the southern states to separate their citizens along racial lines across multiple aspects of life without triggering federal intervention, and most southern states, including Alabama, were not slow to take up the invitation. A wave of constitutional reform spread through the South to authorize harsh local control over African Americans.

Segregation in the Jim Crow Era

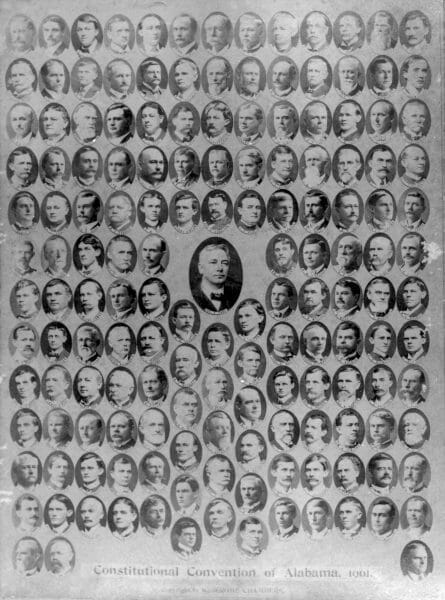

1901 Constitutional Convention

In the wake of the Plessy ruling, Alabama convened another constitutional convention in 1901. Delegates had as one of their main goals the establishment of a state based on white supremacy, and they enshrined separation between whites and African Americans in the constitutional text. Sections 178 and 180 through 182 included provisions specifically designed to disenfranchise Black voters. Section 256 established an entirely segregated school system. Section 102 prevented the legislature from ever allowing interracial marriages. The conventioneers also debated how to define the people they were seeking to control, considering at one point the adoption of a rule that anyone with any degree of African ancestry could be defined as Black. Ultimately, however, they stayed with Alabama’s older definition, which required at least one Black great grandparent for an individual to be subject to Alabama’s many legal restrictions encompassing segregation. The constitution also disenfranchised working-class whites as well. Although the constitution was controversial, it passed and went into effect, giving subsequent legislatures the tools to implement a social and legal system of separation. Localities, too, could begin to apply the laws directly, and did so.

1901 Constitutional Convention

In the wake of the Plessy ruling, Alabama convened another constitutional convention in 1901. Delegates had as one of their main goals the establishment of a state based on white supremacy, and they enshrined separation between whites and African Americans in the constitutional text. Sections 178 and 180 through 182 included provisions specifically designed to disenfranchise Black voters. Section 256 established an entirely segregated school system. Section 102 prevented the legislature from ever allowing interracial marriages. The conventioneers also debated how to define the people they were seeking to control, considering at one point the adoption of a rule that anyone with any degree of African ancestry could be defined as Black. Ultimately, however, they stayed with Alabama’s older definition, which required at least one Black great grandparent for an individual to be subject to Alabama’s many legal restrictions encompassing segregation. The constitution also disenfranchised working-class whites as well. Although the constitution was controversial, it passed and went into effect, giving subsequent legislatures the tools to implement a social and legal system of separation. Localities, too, could begin to apply the laws directly, and did so.

John LeFlore

The effect of the new constitution was readily evident in Mobile the following year. Mobile’s city code had not specifically segregated public transportation, though city officials relied upon custom and intimidation. After the new constitution went into effect, white support for more formal restrictions increased and could be made effective. Although Mobile’s population was nearly half African American, the city council passed an ordinance providing for “separation of the races” on Mobile streetcars by requiring Blacks to sit in the back. Black community leaders and ministers immediately initiated a mass boycott in protest of the policy, and some Blacks who rode the streetcars actively resisted the segregation measure. The boycott, however, gradually collapsed after a few months. Two years after the boycott, a city official ordered Blacks out of Mobile’s oldest public park, and the city council upheld his action, establishing another means of enforcing policies of segregation without passing formal measures. Segregation then progressed rapidly in Mobile as public spaces were increasingly either separated or reserved for whites alone. By 1913, a Black sociologist concluded that Blacks citizens in Mobile lived in an isolated world, utterly separate from whites in most aspects of life and even death, with Blacks and whites being buried in separate cemeteries. The experiences of Mobile’s Black and white citizens were fairly typical for Alabamians in the early twentieth century.

John LeFlore

The effect of the new constitution was readily evident in Mobile the following year. Mobile’s city code had not specifically segregated public transportation, though city officials relied upon custom and intimidation. After the new constitution went into effect, white support for more formal restrictions increased and could be made effective. Although Mobile’s population was nearly half African American, the city council passed an ordinance providing for “separation of the races” on Mobile streetcars by requiring Blacks to sit in the back. Black community leaders and ministers immediately initiated a mass boycott in protest of the policy, and some Blacks who rode the streetcars actively resisted the segregation measure. The boycott, however, gradually collapsed after a few months. Two years after the boycott, a city official ordered Blacks out of Mobile’s oldest public park, and the city council upheld his action, establishing another means of enforcing policies of segregation without passing formal measures. Segregation then progressed rapidly in Mobile as public spaces were increasingly either separated or reserved for whites alone. By 1913, a Black sociologist concluded that Blacks citizens in Mobile lived in an isolated world, utterly separate from whites in most aspects of life and even death, with Blacks and whites being buried in separate cemeteries. The experiences of Mobile’s Black and white citizens were fairly typical for Alabamians in the early twentieth century.

The struggles of the postwar years and late nineteenth century culminated in utter victory for white supremacists in 1901, and systematic social division between the races was the effect. The constitutionally and legally mandated separations were but one facet of segregation. Ordinances and laws established separate school systems and required separate seating in public transportation in many cities. Custom, backed up by the threat of violence from the police or lynch mobs, enforced forms of residential, economic, and social segregation encompassing banking (separate banks), medicine (separate medical practices and hospitals), law (informal exclusion of Blacks on juries), religion (separate churches), and daily life (encompassing separate residential areas, schools, and even cemeteries). If these measures failed to enforce whites’ preferences to avoid associating with Blacks, the state stood ready to step in.

The 1926 case of Wyatt v. Adair offers a good example of state-supported social segregation. Whereas towns could not constitutionally pass ordinances mandating residential segregation by race, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1926 that individuals could agree privately not to rent or sell properties to Blacks. J. E. Adair, a white man, rented a store and a residential floor of a house in Birmingham from W. P. Wyatt, who also was white. Wyatt then leased another residential floor of the house to a Black family, an act made even more outrageous to the Adair family because the entire house shared a single toilet and bathroom. Adair sued on behalf of himself and his family, arguing that Wyatt’s lease of a floor of the same house to a Black family forced him to move (Wyatt v. Adair, 1926). The Alabama Supreme Court supported Adair’s claim, resting its ruling on the ordinary custom of not leasing premises within residences with common toilets to Blacks if whites were already living there. Adair recovered damages, including his lost rent and the expense of moving, but also for the mental anguish caused “by seeing his wife and thirteen-year-old daughter humiliated.” Through this widely cited ruling, the court both approved the principle of segregation and its message of disgust toward Blacks and signaled that it would stand ready to enforce private suits for damages against anyone foolhardy enough to violate the strict norms of separation.

Segregation’s Political Impact and Significance

Rosa Parks’s Symbolic Bus Ride, 1956

The daily process of enforcing segregation influenced how race was defined in Alabama and contributed to the state’s shift toward understanding race as the separation between Blacks and whites, excluding the consideration of other racial groups. Individuals with Native American ancestry lived in some regions of Alabama and built communities that existed separately from Blacks and whites. In the 1920s and early 1930s, some Black Alabamians tried to escape the worst elements of segregation by claiming that they had Native American, rather than Black, ancestors. For instance, one man, Percy Reed, was able to convince an appellate court to overturn his conviction for miscegenation (race mixing) on this basis in Reed v. State in 1922. The state attempted to close this loophole toward the end of the 1920s. In 1927 the legislature amended its definition of Black, shifting to a “one-drop rule” that defined anyone with any Black ancestor as Black. The next year, Alabama’s high court ruled in Weaver v. State that race could be established in a court of law by investigating a person’s appearance, associations, and acquaintances. With this rule in place, practices of compliance with segregation could be used to determine race. In several court cases in the 1920s and 1930s, prosecutors established defendants’ race by showing whether the person had gone to a Black or white church or school and how the person interacted with Blacks and whites. Individuals who had attended Black schools or belonged to Black churches or interacted primarily with Black socially were more readily deemed Black by Alabama’s legal system, even if they did not appear to be “Black.”

Rosa Parks’s Symbolic Bus Ride, 1956

The daily process of enforcing segregation influenced how race was defined in Alabama and contributed to the state’s shift toward understanding race as the separation between Blacks and whites, excluding the consideration of other racial groups. Individuals with Native American ancestry lived in some regions of Alabama and built communities that existed separately from Blacks and whites. In the 1920s and early 1930s, some Black Alabamians tried to escape the worst elements of segregation by claiming that they had Native American, rather than Black, ancestors. For instance, one man, Percy Reed, was able to convince an appellate court to overturn his conviction for miscegenation (race mixing) on this basis in Reed v. State in 1922. The state attempted to close this loophole toward the end of the 1920s. In 1927 the legislature amended its definition of Black, shifting to a “one-drop rule” that defined anyone with any Black ancestor as Black. The next year, Alabama’s high court ruled in Weaver v. State that race could be established in a court of law by investigating a person’s appearance, associations, and acquaintances. With this rule in place, practices of compliance with segregation could be used to determine race. In several court cases in the 1920s and 1930s, prosecutors established defendants’ race by showing whether the person had gone to a Black or white church or school and how the person interacted with Blacks and whites. Individuals who had attended Black schools or belonged to Black churches or interacted primarily with Black socially were more readily deemed Black by Alabama’s legal system, even if they did not appear to be “Black.”

In some ways, segregation enabled moderate whites to provide limited benefits and accommodations for Blacks without threatening white supremacy. The development of separate public library systems was an example. The first public library branch for African Americans opened in Birmingham in 1918. Some whites supported segregated library branches as a non-threatening vehicle for Blacks’ social improvement. Library branches for Blacks primarily in urban environments grew slowly until pressure from Black civic and religious leaders, educators, and librarians promoted the establishment of more library branches in the 1940s and early 1950s. These efforts to expand access to segregated libraries were eclipsed by the Read-in Movement of the late 1950s and early 1960s, in which Blacks in Alabama used sit-ins to desegregate public libraries.

Colored Masonic Temple in Birmingham

If there was a positive outcome for African Americans from the years of segregation, it was that segregation generated vitally strong all-Black institutions, which supported individual Blacks and provided space for the development of autonomous Black leadership. For instance, Birmingham’s all-Black Masonic Hall provided an organizing site for Birmingham’s radical union movement in the 1930s. Black churches, in addition to providing spiritual community and leadership, sometimes provided meeting space and cover for political discussions, including local NAACP chapters, and the development of organized resistance and mutual protection. Some Black teachers in segregated schools modeled independence and pride for their students. The total nature of segregation and its deep tentacles, which spread throughout Alabama’s culture, law, and society, however, rendered it impervious to successful systemic attack until the emergence of the civil rights movement and its tactics of mass protest.

Colored Masonic Temple in Birmingham

If there was a positive outcome for African Americans from the years of segregation, it was that segregation generated vitally strong all-Black institutions, which supported individual Blacks and provided space for the development of autonomous Black leadership. For instance, Birmingham’s all-Black Masonic Hall provided an organizing site for Birmingham’s radical union movement in the 1930s. Black churches, in addition to providing spiritual community and leadership, sometimes provided meeting space and cover for political discussions, including local NAACP chapters, and the development of organized resistance and mutual protection. Some Black teachers in segregated schools modeled independence and pride for their students. The total nature of segregation and its deep tentacles, which spread throughout Alabama’s culture, law, and society, however, rendered it impervious to successful systemic attack until the emergence of the civil rights movement and its tactics of mass protest.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled against segregated schools in Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, and the Montgomery Bus Boycott challenging segregated public transportation started in 1955. These two important events signaled the beginning of the end for segregation in Alabama. While years of struggle would follow, the major elements of segregation were toppled by Congress as the Civil Rights Act of 1964 banned segregation in public accommodations and employment and gave the federal government enforcement powers. Later, the Civil Rights Act of 1968 prohibited discrimination in housing. Federal courts also contributed by ordering individual school districts and other institutions like public parks to desegregate and by supporting civil rights protesters in legal conflicts over sit-ins and marches. By the end of the 1960s, the state was no longer legally permitted to separate whites and Blacks in all elements of daily life, and the regime of segregation had ended.

Further Reading

- Alsobrook, David. 2003. “The Mobile Streetcar Boycott of 1902: African American Protest or Capitulation?” Alabama Review 56: 83-102.

- Chafe, William. 2000. “The Gods Bring Threads to Webs Begun.” Journal of American History 86: 1-54.

- Flynt, Wayne. 2001. “Alabama’s Shame: The Historical Origins of the 1901 Constitution.” Alabama Law Review 53: 67-76.

- Graham, Patterson Toby. 2003. A Right to Read: Segregation and Civil Rights in Alabama’s Public Libraries, 1900-1965. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

- Morgan, Martha, and Neal Hutchens. 2001. “The Tangled Web of Alabama’s Equality Doctrine After Melof: Historical Reflections on Equal Protection and the Alabama Constitution.” Alabama Law Review 53: 135-242.

- Rogers, William Warren, Robert David Ward, Leah Rawls Atkins, and Wayne Flynt. 1984. Alabama: The History of a Deep-South State. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.