Airports in Alabama

Birmingham-Shuttlesworth International Airport

In Alabama, as in most states, airports have expanded in number and size in conjunction with the growth of commercial air travel; changes in state, federal, and local regulatory and fiscal responsibilities; and decisions about military base acquisitions and closures. Alabama was home to the first civilian flying school in the nation, and today its public-use airports are an integral part of the state’s transportation network. Airports have been viewed as indicators of community progress, but their development often has been hampered by local and state economic policies and decisions. More than six million passengers pass through the state’s 96 active public-use airports every year. Two airports—Birmingham-Shuttlesworth International Airport and Huntsville International Airport—host international service, with direct flights to Canada and Europe. Mobile, Montgomery, Dothan, and northwest Alabama (near Muscle Shoals) have regional airports providing scheduled commercial service. The state’s 148 airports provide facilities for fixed-base operators, flight schools, helicopters, aerial surveying, police and fire protection, and activities in support of agriculture.

Birmingham-Shuttlesworth International Airport

In Alabama, as in most states, airports have expanded in number and size in conjunction with the growth of commercial air travel; changes in state, federal, and local regulatory and fiscal responsibilities; and decisions about military base acquisitions and closures. Alabama was home to the first civilian flying school in the nation, and today its public-use airports are an integral part of the state’s transportation network. Airports have been viewed as indicators of community progress, but their development often has been hampered by local and state economic policies and decisions. More than six million passengers pass through the state’s 96 active public-use airports every year. Two airports—Birmingham-Shuttlesworth International Airport and Huntsville International Airport—host international service, with direct flights to Canada and Europe. Mobile, Montgomery, Dothan, and northwest Alabama (near Muscle Shoals) have regional airports providing scheduled commercial service. The state’s 148 airports provide facilities for fixed-base operators, flight schools, helicopters, aerial surveying, police and fire protection, and activities in support of agriculture.

Birmingham Fairgrounds Air Show 1912

In search of a warm-weather site to instruct student pilots, flight pioneers Wilbur and Orville Wright established the first landing field in the state in the spring of 1910 on an old cotton plantation west of Montgomery. Now the site of Maxwell Air Force Base, the Wright brothers’ operation has the distinction of being the nation’s first flight-training school for civilians. Before World War I, the public regarded flying and airplanes mostly as entertainment, and their curiosity about the new technology was satisfied by daring exhibitions at fairgrounds and racetracks. The State Fairgrounds in Birmingham saw regular flying demonstrations from 1912 to 1915, as did the annual Montgomery County Fair. During World War I, a handful of Alabamians joined the army and received military flight training, thus generating wider interest in the airplane and flying. Some learned to fly at Taylor Field, established in Montgomery in 1917 and one of only 13 army primary flight-training facilities in the nation. After the war, Alabama had a wealth of surplus aircraft, a nucleus of skilled and enthusiastic aviators, and a federal government committed to the growth of aviation, all of which combined to bring about the state’s first permanent airports. Members of the Birmingham Flying Club, all of whom were World War I fliers or had military experience, generated interest in aviation through the creation of an air unit of the Alabama National Guard and welcomed itinerant “barnstorming” pilots who put on shows and offered flight lessons. Birmingham’s first airport, Dixie Field, opened in 1919, followed in 1922 by Roberts Field, which served as the city’s municipal airport for the rest of the decade.

Birmingham Fairgrounds Air Show 1912

In search of a warm-weather site to instruct student pilots, flight pioneers Wilbur and Orville Wright established the first landing field in the state in the spring of 1910 on an old cotton plantation west of Montgomery. Now the site of Maxwell Air Force Base, the Wright brothers’ operation has the distinction of being the nation’s first flight-training school for civilians. Before World War I, the public regarded flying and airplanes mostly as entertainment, and their curiosity about the new technology was satisfied by daring exhibitions at fairgrounds and racetracks. The State Fairgrounds in Birmingham saw regular flying demonstrations from 1912 to 1915, as did the annual Montgomery County Fair. During World War I, a handful of Alabamians joined the army and received military flight training, thus generating wider interest in the airplane and flying. Some learned to fly at Taylor Field, established in Montgomery in 1917 and one of only 13 army primary flight-training facilities in the nation. After the war, Alabama had a wealth of surplus aircraft, a nucleus of skilled and enthusiastic aviators, and a federal government committed to the growth of aviation, all of which combined to bring about the state’s first permanent airports. Members of the Birmingham Flying Club, all of whom were World War I fliers or had military experience, generated interest in aviation through the creation of an air unit of the Alabama National Guard and welcomed itinerant “barnstorming” pilots who put on shows and offered flight lessons. Birmingham’s first airport, Dixie Field, opened in 1919, followed in 1922 by Roberts Field, which served as the city’s municipal airport for the rest of the decade.

Roberts Field

In 1927, Charles A. Lindbergh’s solo transatlantic flight further sparked public interest in aviation. Local civic boosters and federal initiatives through the Department of Commerce, and the creation of the airmail system, combined with public interest to produce a boom in airport building. St. Tammany Gulf Coast Airways used Roberts Field in 1928 for the state’s first regularly scheduled commercial air service, which included a stop at Bates Field, Mobile’s municipal airport, on the route between Atlanta and New Orleans. Montgomery opened its first municipal airport in 1929 and served as a stop for Southern Air Express passenger service to Atlanta and Jackson, Mississippi. In 1931, Birmingham replaced Roberts Field with a big new municipal airport and passenger service to Dallas, Atlanta, and other cities. Huntsville’s municipal airport opened later that year, but it proved too small to attract airlines to the city. By this time the state had 29 airports, including 10 designated as municipal or commercial fields.

Roberts Field

In 1927, Charles A. Lindbergh’s solo transatlantic flight further sparked public interest in aviation. Local civic boosters and federal initiatives through the Department of Commerce, and the creation of the airmail system, combined with public interest to produce a boom in airport building. St. Tammany Gulf Coast Airways used Roberts Field in 1928 for the state’s first regularly scheduled commercial air service, which included a stop at Bates Field, Mobile’s municipal airport, on the route between Atlanta and New Orleans. Montgomery opened its first municipal airport in 1929 and served as a stop for Southern Air Express passenger service to Atlanta and Jackson, Mississippi. In 1931, Birmingham replaced Roberts Field with a big new municipal airport and passenger service to Dallas, Atlanta, and other cities. Huntsville’s municipal airport opened later that year, but it proved too small to attract airlines to the city. By this time the state had 29 airports, including 10 designated as municipal or commercial fields.

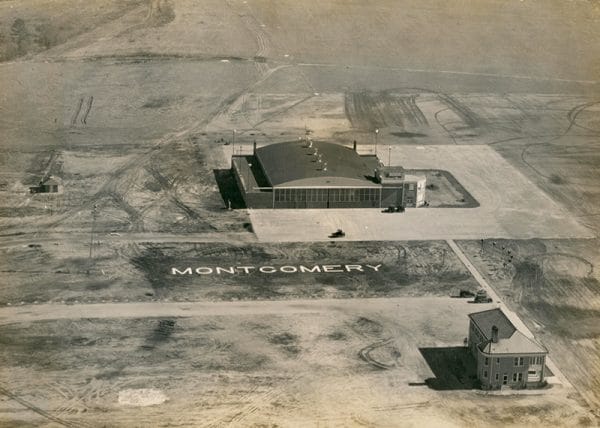

Montgomery Municipal Airport 1930

During the 1930s, despite the economic ravages of the Great Depression, commercial aviation expanded with the help of partnerships in airport development along local, state, and federal agencies. Before this time, the federal government had treated airports as it did docks and harbor facilities, expecting them to be financed by municipalities and private interests. Under Pres. Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal programs, however, states received direct federal support for airport construction through various public works programs, including 24 airport projects in Alabama. In 1935, the state legislature created the Alabama Aviation Commission to stimulate construction of public airports and oversee disbursement of federal funds. Commissioner Asa Rountree Jr. (son of Good Roads pioneer John Asa Rountree) saw the development of aviation as an indicator of economic progress and dedicated himself to expanding and improving the state’s airports during his three-decade career. Between 1935 and 1942, 42 airport projects were completed in the state, and Montgomery and Birmingham upgraded their municipal airports and expanded passenger air service. Huntsville’s new municipal field opened in 1941 to limited operations.

Montgomery Municipal Airport 1930

During the 1930s, despite the economic ravages of the Great Depression, commercial aviation expanded with the help of partnerships in airport development along local, state, and federal agencies. Before this time, the federal government had treated airports as it did docks and harbor facilities, expecting them to be financed by municipalities and private interests. Under Pres. Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal programs, however, states received direct federal support for airport construction through various public works programs, including 24 airport projects in Alabama. In 1935, the state legislature created the Alabama Aviation Commission to stimulate construction of public airports and oversee disbursement of federal funds. Commissioner Asa Rountree Jr. (son of Good Roads pioneer John Asa Rountree) saw the development of aviation as an indicator of economic progress and dedicated himself to expanding and improving the state’s airports during his three-decade career. Between 1935 and 1942, 42 airport projects were completed in the state, and Montgomery and Birmingham upgraded their municipal airports and expanded passenger air service. Huntsville’s new municipal field opened in 1941 to limited operations.

Bates Field Airport 1946

Alabama’s airports were integral to the nation’s defense during World War II, facilitating the movement of troops and material as well as providing training facilities for pilots and support personnel. In 1940 the Development of Landing Areas for National Defense (DLAND) program began funding major airport construction and improvement projects. That year, Mobile used federal funding for runway and other improvements, and in 1942 its airport became home to a large army glider training program. The city of Dothan and Houston County provided funds to buy land for an airport, opened in 1941 as Napier Field, that served as a training facility for army aviators. Under DLAND, Huntsville’s new municipal airport received funds for runway and other improvements that led to the city’s first passenger airline service in 1944. Birmingham Municipal Airport was the site of an army air forces support base and a heavy bomber modification facility. In 1943 the army took over Montgomery’s municipal airport for flight training, and the city received federal funding for a new airport, Dannelly Field. The army built airfields at Huntsville’s Redstone Arsenal and Ozark‘s Fort Novosel (formerly Fort Rucker) as well as in Courtland, Selma, Tuscaloosa, and Tuskegee (home of the famed Tuskegee Airmen). After the war, the government turned a number of these facilities over to local communities for further development as public-use airports.

Bates Field Airport 1946

Alabama’s airports were integral to the nation’s defense during World War II, facilitating the movement of troops and material as well as providing training facilities for pilots and support personnel. In 1940 the Development of Landing Areas for National Defense (DLAND) program began funding major airport construction and improvement projects. That year, Mobile used federal funding for runway and other improvements, and in 1942 its airport became home to a large army glider training program. The city of Dothan and Houston County provided funds to buy land for an airport, opened in 1941 as Napier Field, that served as a training facility for army aviators. Under DLAND, Huntsville’s new municipal airport received funds for runway and other improvements that led to the city’s first passenger airline service in 1944. Birmingham Municipal Airport was the site of an army air forces support base and a heavy bomber modification facility. In 1943 the army took over Montgomery’s municipal airport for flight training, and the city received federal funding for a new airport, Dannelly Field. The army built airfields at Huntsville’s Redstone Arsenal and Ozark‘s Fort Novosel (formerly Fort Rucker) as well as in Courtland, Selma, Tuscaloosa, and Tuskegee (home of the famed Tuskegee Airmen). After the war, the government turned a number of these facilities over to local communities for further development as public-use airports.

Huntsville International Airport

In the postwar era, the expansion of commercial aviation in the state hinged on continued funding for airport development. In 1945, the Alabama Aviation Commission became the Alabama Aeronautics Commission with more autonomy as the governing body for the new Alabama Department of Aeronautics. The Federal Airport Act of 1946 established the Federal Aid Airport Program, which allowed cities to apply directly to the U.S. government for airport funding. Convinced that large urban centers would absorb most of the federal resources, Rountree inaugurated a program within the Alabama Aeronautics Commission in 1954 to develop small landing fields in poor and rural areas of the state. The program relied exclusively on state money, accumulated through an aviation fuel tax. Critics claimed the tax discouraged airlines from basing their aircraft at larger Alabama airports because the tax burden was higher than in neighboring states.

Huntsville International Airport

In the postwar era, the expansion of commercial aviation in the state hinged on continued funding for airport development. In 1945, the Alabama Aviation Commission became the Alabama Aeronautics Commission with more autonomy as the governing body for the new Alabama Department of Aeronautics. The Federal Airport Act of 1946 established the Federal Aid Airport Program, which allowed cities to apply directly to the U.S. government for airport funding. Convinced that large urban centers would absorb most of the federal resources, Rountree inaugurated a program within the Alabama Aeronautics Commission in 1954 to develop small landing fields in poor and rural areas of the state. The program relied exclusively on state money, accumulated through an aviation fuel tax. Critics claimed the tax discouraged airlines from basing their aircraft at larger Alabama airports because the tax burden was higher than in neighboring states.

Montgomery Regional Airport

Despite the controversy over airport funding and the fuel tax, the state and its residents were committed to the new postwar “air age.” Significant changes came to Alabama airports in the 1950s and 1960s as a result. As Rountree predicted, the lion’s share of federal airport aid went to the state’s large airports. Birmingham and Huntsville used the federal money to construct new runways and improve older ones. In 1963, the state legislature passed the Airport Authority Act, which allowed local governments to create airport planning agencies and empowered them to issue bonds to pay for airport development. Four years later, the Alabama legislature lowered the aviation fuel tax, but there was no consequent upswing in airline traffic. The 1960s saw a moderate increase in scheduled aircraft departures in Birmingham, but Huntsville, the state’s second busiest airport, saw no increase, and Mobile’s traffic jumped only slightly. Additionally, the advent of jet airliners meant more passengers could be accommodated on accelerated schedules, causing an increase in the number of people flying and requiring upgraded terminal facilities and improved runways and taxiways to handle bigger aircraft. During the decade airline passengers increased from 460,000 statewide to nearly 1.2 million, placing additional burdens on the state’s airports. With more federal and state funding in the late 1960s, Alabama’s airports added new runways, extended older ones, added lighting, and made other improvements that included new or expanded terminals. Dothan completed a new terminal building in 1965. The Huntsville and Mobile airports were unable to expand because of geographical constraints and thus acquired additional properties to accommodate more and larger aircraft in 1967 and 1969, respectively.

Montgomery Regional Airport

Despite the controversy over airport funding and the fuel tax, the state and its residents were committed to the new postwar “air age.” Significant changes came to Alabama airports in the 1950s and 1960s as a result. As Rountree predicted, the lion’s share of federal airport aid went to the state’s large airports. Birmingham and Huntsville used the federal money to construct new runways and improve older ones. In 1963, the state legislature passed the Airport Authority Act, which allowed local governments to create airport planning agencies and empowered them to issue bonds to pay for airport development. Four years later, the Alabama legislature lowered the aviation fuel tax, but there was no consequent upswing in airline traffic. The 1960s saw a moderate increase in scheduled aircraft departures in Birmingham, but Huntsville, the state’s second busiest airport, saw no increase, and Mobile’s traffic jumped only slightly. Additionally, the advent of jet airliners meant more passengers could be accommodated on accelerated schedules, causing an increase in the number of people flying and requiring upgraded terminal facilities and improved runways and taxiways to handle bigger aircraft. During the decade airline passengers increased from 460,000 statewide to nearly 1.2 million, placing additional burdens on the state’s airports. With more federal and state funding in the late 1960s, Alabama’s airports added new runways, extended older ones, added lighting, and made other improvements that included new or expanded terminals. Dothan completed a new terminal building in 1965. The Huntsville and Mobile airports were unable to expand because of geographical constraints and thus acquired additional properties to accommodate more and larger aircraft in 1967 and 1969, respectively.

Dothan Regional Airport

The increase in airline passengers continued through the 1970s, climbing from 2.6 million to more than 3.2 million, before falling off in the early 1980s during the economic recession. Birmingham pinned its hopes to become an airline hub in the 1980s on airport improvements and special state tax exemptions, only to be frustrated by the realities of the highly volatile airline industry in an era of economic deregulation, which led to more competition, lower fares in some markets, and a distressing number of airline bankruptcies. Established carrier Delta and new low-cost Southwest Airlines enjoyed the tax exemptions in the 1990s and offered more flights from Birmingham but did not establish hubs in the city. In 1999, Dothan, Montgomery, Muscle Shoals, and Mobile were designated regional airports, with additional airline connections to cities outside the state. The state’s largest airport, Birmingham-Shuttlesworth International, renamed in July 2008 to honor Fred Shuttlesworth, a pioneering civil rights advocate, continued expansion projects begun earlier in the decade to accommodate steady increases in passenger traffic.

Dothan Regional Airport

The increase in airline passengers continued through the 1970s, climbing from 2.6 million to more than 3.2 million, before falling off in the early 1980s during the economic recession. Birmingham pinned its hopes to become an airline hub in the 1980s on airport improvements and special state tax exemptions, only to be frustrated by the realities of the highly volatile airline industry in an era of economic deregulation, which led to more competition, lower fares in some markets, and a distressing number of airline bankruptcies. Established carrier Delta and new low-cost Southwest Airlines enjoyed the tax exemptions in the 1990s and offered more flights from Birmingham but did not establish hubs in the city. In 1999, Dothan, Montgomery, Muscle Shoals, and Mobile were designated regional airports, with additional airline connections to cities outside the state. The state’s largest airport, Birmingham-Shuttlesworth International, renamed in July 2008 to honor Fred Shuttlesworth, a pioneering civil rights advocate, continued expansion projects begun earlier in the decade to accommodate steady increases in passenger traffic.

Alabama airports proved not to be the leading sectors of economic development that many hoped they would be in the twentieth century, and the state continues to lag behind its neighbors in attracting and retaining major national and regional airline connections. The Alabama Department of Transportation, which absorbed the Alabama Department of Aeronautics in 2000, has secured more federal funding for regional and smaller public-use airports. Despite the political and economic uncertainties of the new century, the state’s airports are and will continue to be vital links from Alabama to the rest of the nation and the world beyond.

Further Reading

- “Alabama Aviation in the First Century of Flight.” Special Issue, Alabama Review 57 (January 2004).

- Bednarek, Janet R. Daly. America’s Airports: Airfield Development, 1918-1947. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2001.

- Dodd, Don, and Amy Bartlett-Dodd. Deep South Aviation. Birmingham, Ala.: Southern Museum of Flight Foundation, 1999.

- Rountree, Asa, Jr. Aviation in Alabama and 24 Years of Service by the Alabama Department of Aeronautics, 1935-1959. Montgomery: Alabama Department of Aeronautics, 1960.