Gandy Dancer Work Song Tradition

Gandy Dancers

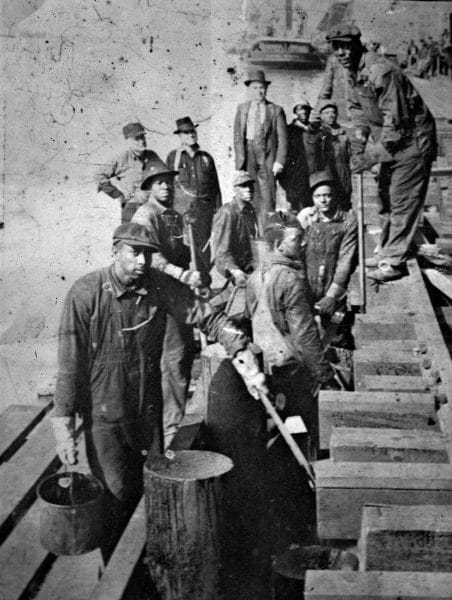

“Gandy dancers” was a nickname for railroad section gangs in the days before modern mechanized track upkeep. The men were called dancers for their synchronized movements when repairing track under the direction of a lead workman known as the “caller” or “call man.” The name “gandy” supposedly arose from a belief that their hand tools once came from the Gandy tool company in Chicago (though no researcher has ever turned up such a company that made railroad tools). The name may also have derived from “gander” because the flat-footed steps of the workmen when lining track resembled the way that geese walk. There is, however, no consensus on the origin of the name.

Gandy Dancers

“Gandy dancers” was a nickname for railroad section gangs in the days before modern mechanized track upkeep. The men were called dancers for their synchronized movements when repairing track under the direction of a lead workman known as the “caller” or “call man.” The name “gandy” supposedly arose from a belief that their hand tools once came from the Gandy tool company in Chicago (though no researcher has ever turned up such a company that made railroad tools). The name may also have derived from “gander” because the flat-footed steps of the workmen when lining track resembled the way that geese walk. There is, however, no consensus on the origin of the name.

Each group of railroad workers, known as section gangs, typically maintained 10 to 15 miles of track. The men refilled the ballast (gravel) between the railroad ties, replaced rotted crossties, and either turned or replaced worn rails, driving spikes to lock them to the crossties. Spike driving required no group coordination, but the heavy rails had to be carried by teams of men with large clamps called “rail dogs.” A lead singer coordinated the effort with so-called “dogging” calls. A good half of a typical workday was spent on the constant chore of straightening out the track (known as lining), and it was from this activity that “gandy dancers” earned their name. When leveling the track, workmen jacked up the track at its low spots and pushed ballast under the raised ties with square-ended picks, often leaning shoulder-to-shoulder in pairs while the caller marked time with a four-beat “tamping” song.

Gandy Dancers Raising a Rail

In the South in general and Alabama specifically, at least through the 1950s, the foreman of a section gang was invariably white and the members of the gang itself almost exclusively African American. The foreman typically positioned himself 50 yards or more from the section gang, squatted down, and examined the length of track for problems. He used visual signals to tell the caller where the track was out of alignment and when it was “lined” properly. At the time, rails typically came in 13-yard (12-meter) lengths. The section gang systematically aligned the rails at the joints and at specified points along its length in a well-defined order.

Gandy Dancers Raising a Rail

In the South in general and Alabama specifically, at least through the 1950s, the foreman of a section gang was invariably white and the members of the gang itself almost exclusively African American. The foreman typically positioned himself 50 yards or more from the section gang, squatted down, and examined the length of track for problems. He used visual signals to tell the caller where the track was out of alignment and when it was “lined” properly. At the time, rails typically came in 13-yard (12-meter) lengths. The section gang systematically aligned the rails at the joints and at specified points along its length in a well-defined order.

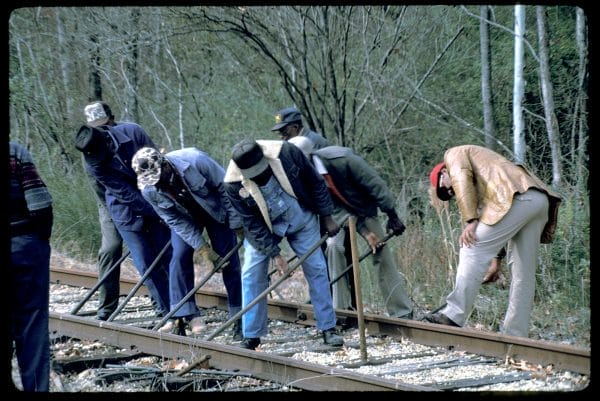

Section gangs were made up of as few as four men but might include as many as 30 men, depending on the workload. Each workman carried a lining bar, a straight pry bar with a sharp end. The thicker bottom end was square-shafted (to fit against the rail) and shaped to a chisel point (to dig down into the gravel underneath the rail); the lighter top end was rounded (for better gripping). When lining track, each man would face one of the rails and work the chisel end of his lining bar down at an angle into the ballast under it. Then all would take a step toward their rail and pull up and forward on their pry bars to lever the track—rails, crossties and all—over and through the ballast.

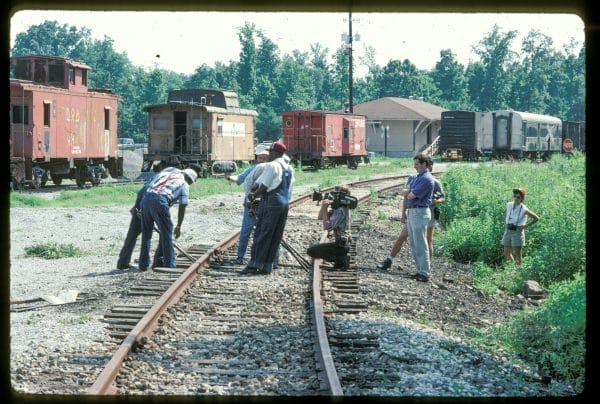

Gandy Dancers Demonstration

Lining track was difficult, tedious work, and the timing or coordination of the pull was more important than the brute force put forth by any single man. It was the job of the caller to maintain this coordination. He simultaneously motivated and entertained the men and set the timing through work songs that derived distantly from sea chanteys and more recently from cotton-chopping songs, blues, and African-American church music. Typical songs featured a two-line, four-beat couplet to which members of the gang would tap their lining bars against the rails, as in this example:

Gandy Dancers Demonstration

Lining track was difficult, tedious work, and the timing or coordination of the pull was more important than the brute force put forth by any single man. It was the job of the caller to maintain this coordination. He simultaneously motivated and entertained the men and set the timing through work songs that derived distantly from sea chanteys and more recently from cotton-chopping songs, blues, and African-American church music. Typical songs featured a two-line, four-beat couplet to which members of the gang would tap their lining bars against the rails, as in this example:

1 2 3 4 “O joint ahead and quarter back”

1 2 3 4 “That’s the way we line this track”

When the liners were tapping in perfect time, he would call for a hearty pull on the third beat of a four-beat refrain:

1 2 3 4 “Come on, move it! Huhn! (pause)”

1 2 3 4 “Boys, can you move it! Uhmm! (pause)”

and so on until the foreman signaled that the track was properly aligned. A good caller could call all day and never repeat the same phrase twice. Veteran section gangs lining track, especially with an audience, often embellished their work with a one-handed flourish and with one foot stepping out and back on beats four, one, and two, between the two-armed pulls on the lining bars on beat three.

In a ceremony at the Smithsonian in 1996, John Henry Mealing (who had worked on the Western and then the Frisco lines) and Cornelius Wright (who had worked on U.S. Steel’s 1,100 miles of track), two former callers of this kind of work song in central Alabama, received National Heritage Fellowship Awards as “Master Folk and Traditional Artists” for their demonstrations of this form of African-American folk art.

Music Recording

Further Reading

- Courlander, Harold. Negro Songs from Alabama. Rev. & enl. 2nd ed. New York: Oak Publications, 1963.

- Corn Bread Crumbled in Gravy: Historical Alabama Field Recordings from the Byron Arnold Collection of Traditional Tunes. Audiocassette. Produced by Joy D. Baklanoff and John Bealle. Montgomery: Alabama Folklife Association, 1992.

- Gandy Dancers. VHS. Directed by Maggie Holtzberg-Call and Barry Dornfield. New York: Cinema Guild, 1994.

- Lomax, Alan. The Folk Songs of North America in the English Language. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1960.

- Traditional Musics of Alabama: A Compilation. Compact disc. Produced by Steve Grauberger. Montgomery: Alabama Center for Traditional Culture, Alabama State Council on the Arts, 2002.