Whig Party

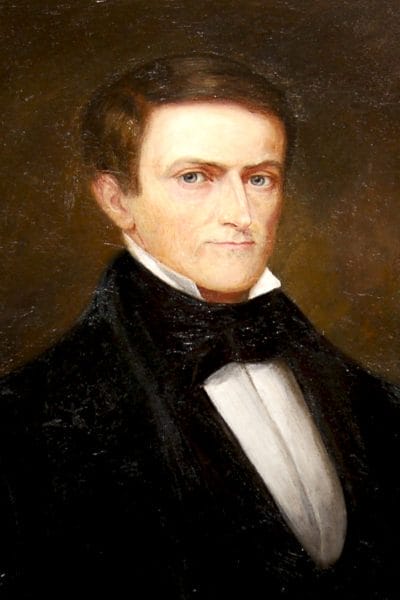

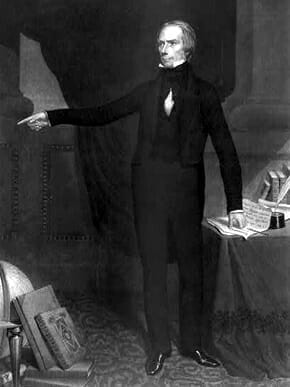

Henry Clay

The Whig Party developed during the presidency of Andrew Jackson and enjoyed success in Alabama from the 1830s to the early 1850s. Whigs achieved early political gains during a period of economic depression in the late 1830s. Party gains in the 1840s resulted from divisions among Democrats, but the Whigs never gained control of the state. In the 1850s, the Whig Party’s agenda of economic expansion and moral reform was undermined by prosperity and its unity shattered by the issue of southern rights related to the expansion of slavery and fears of federal power. Additionally, successful Democratic leadership and adaptability forced the Whigs into a politically reactive rather than proactive position. Alabama’s Whig Party ultimately foundered on the issue of slavery, which Alabama Democrats were able to effectively exploit among the electorate.

Henry Clay

The Whig Party developed during the presidency of Andrew Jackson and enjoyed success in Alabama from the 1830s to the early 1850s. Whigs achieved early political gains during a period of economic depression in the late 1830s. Party gains in the 1840s resulted from divisions among Democrats, but the Whigs never gained control of the state. In the 1850s, the Whig Party’s agenda of economic expansion and moral reform was undermined by prosperity and its unity shattered by the issue of southern rights related to the expansion of slavery and fears of federal power. Additionally, successful Democratic leadership and adaptability forced the Whigs into a politically reactive rather than proactive position. Alabama’s Whig Party ultimately foundered on the issue of slavery, which Alabama Democrats were able to effectively exploit among the electorate.

The Whig Party’s origins in Alabama can be traced to a series of issues that arose during the early days of statehood. Differences between the northern and southern parts of the state in terms of topography, climate, and farm production created differing economic interests that pitted hill-country, small-scale farmers against planters with large land-holdings. Economic and political domination by the leadership of the Planters and Merchants Bank (or Huntsville Bank), often called the Broad River Group, also created perceptions among Alabama’s citizens that the state government was being run by the moneyed classes. Nationally, the presidential contest of 1824, in which the lone Democratic-Republican Party split into four factions, produced suspicions that a political elite led by John Quincy Adams and Henry Clay had stolen the election from candidate Andrew Jackson. Kentuckian Clay, Speaker of the House of Representatives in Congress, had earlier pushed through legislation that imposed tariffs. He also favored federal funding for national roads, harbors, and other improvements. Although Clay’s actions were aimed at boosting the national economy, they raised questions among southerners about economic equity and the rights of the states to run their own affairs without federal government interference. These developments gradually divided the citizenry of the entire country, including Alabama, into two camps: the Democratic-Republican followers of Andrew Jackson and the National-Republican supporters of national economic expansion, led by Clay. Among the latter were also opponents of Jackson’s heavy-handed policies as president.

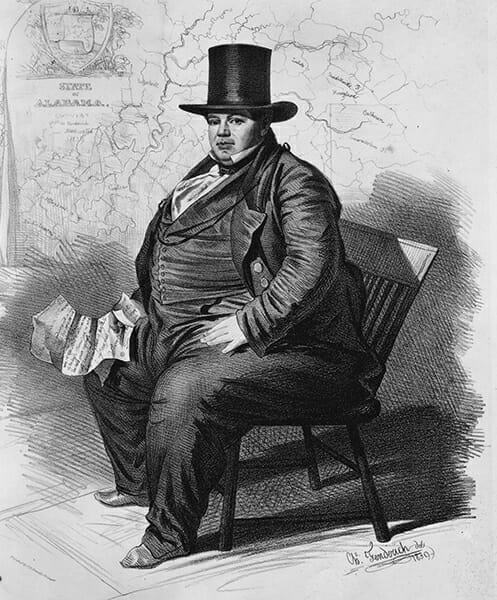

Dixon Hall Lewis

In the 1830s, the differences deepened between these groups in Alabama and throughout the country. Jackson’s veto of the re-chartering of the Bank of the United States because of his dislike of the institution worried some Alabamians who benefited from the bank’s lending policies and feared an increase in presidential power. Some even began to call Jackson “King Andrew.” Other opponents of Jackson included Alabama states’-rights advocates, such as Dixon Hall Lewis, who opposed federal tariffs on imports because those high taxes harmed southern growers and merchants who sold goods in foreign markets. They supported South Carolina’s declaration that the federal tariff was unconstitutional and its efforts to invalidate that law in 1832–33, and opposed Jackson’s strong stand against that state. The president’s handling of the disposition of Creek Indian lands in Alabama raised further fears of executive power when he used military force to remove Alabamians who had squatted on Indian lands before they were made available for settlement.

Dixon Hall Lewis

In the 1830s, the differences deepened between these groups in Alabama and throughout the country. Jackson’s veto of the re-chartering of the Bank of the United States because of his dislike of the institution worried some Alabamians who benefited from the bank’s lending policies and feared an increase in presidential power. Some even began to call Jackson “King Andrew.” Other opponents of Jackson included Alabama states’-rights advocates, such as Dixon Hall Lewis, who opposed federal tariffs on imports because those high taxes harmed southern growers and merchants who sold goods in foreign markets. They supported South Carolina’s declaration that the federal tariff was unconstitutional and its efforts to invalidate that law in 1832–33, and opposed Jackson’s strong stand against that state. The president’s handling of the disposition of Creek Indian lands in Alabama raised further fears of executive power when he used military force to remove Alabamians who had squatted on Indian lands before they were made available for settlement.

In 1834, the president’s opponents throughout the nation organized as the Whigs, choosing the name from the British Whig Party that had opposed the monarchy. Jackson’s selection of Martin Van Buren as his successor, a New Yorker suspected of being opposed to slavery, further solidified the nascent party in the South. In the presidential contest of 1836, southern Whig candidate Hugh Lawson White received a significant number of votes in Alabama, although Van Buren still won the state. This election marked the emergence of the Whigs as a viable party in Alabama, but the members were united only by their opposition to Jackson. There were significant differences among members regarding the issues of federal power versus states’ rights, economic expansion, and the growing controversy over slavery.

With the onset of the economic depression known as the Panic of 1837, Alabama Whigs called for federal relief and the establishment of a new Bank of the United States. The increasing insolvency of the state bank of Alabama strengthened their arguments. In this period, new leaders emerged, such as Henry W. Hilliard, Arthur F. Hopkins, and Lewis E. Parsons. They reorganized the party, held conventions, and led the Whigs to improved showings in the state elections of 1839, though the party did not win the governorship or control of the legislature.

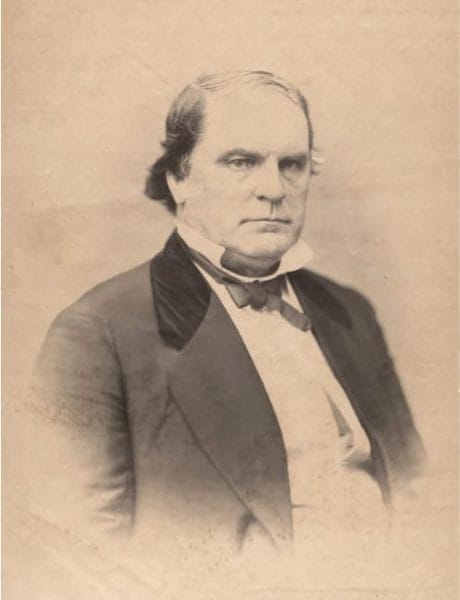

Lewis E. Parsons

By 1840, Alabama’s Whig Party had matured. Its leaders believed in economic development encouraged by a government banking system, support for business, and aid for internal improvements such as roads, railroads, and canals. National issues were important, particularly as opposition to slavery increased, but local considerations and candidate popularity also played a role in party identity. The age distribution of men in the party was similar to that of the Democrats, except for a slight tendency of men over 40 to lean toward the Whigs. Views regarding slaveholding, land ownership, and occupational distributions also were nearly identical in both parties, but Whig numbers were stronger in the river valleys throughout the state and in coastal regions where men were more involved in commerce with the outside world. In these areas party objectives tended to fit more closely with commercial interests.

Lewis E. Parsons

By 1840, Alabama’s Whig Party had matured. Its leaders believed in economic development encouraged by a government banking system, support for business, and aid for internal improvements such as roads, railroads, and canals. National issues were important, particularly as opposition to slavery increased, but local considerations and candidate popularity also played a role in party identity. The age distribution of men in the party was similar to that of the Democrats, except for a slight tendency of men over 40 to lean toward the Whigs. Views regarding slaveholding, land ownership, and occupational distributions also were nearly identical in both parties, but Whig numbers were stronger in the river valleys throughout the state and in coastal regions where men were more involved in commerce with the outside world. In these areas party objectives tended to fit more closely with commercial interests.

During the 1840 election cycle, Alabama’s Whigs focused on the economic depression and the failure of the Democrats to deal effectively with it. They consequently made gains against the Democratic majority in the state legislature. In the presidential campaign, they accused Democrat Martin Van Buren of being soft on slavery and causing the depression. Van Buren triumphed in Alabama, but the Whigs won 45 percent of the popular vote.

Whig successes at the polls worried state Democrats, and under the leadership of Gov. Arthur Bagby, they enacted a general-ticket system for the state’s congressional elections. This plan eliminated district divisions and allowed balloting for representatives on a statewide basis, which meant that votes in formerly Whig districts were cancelled out by heavily Democratic turnouts in other areas of the state. The plan worked, and the Democrats won all five of Alabama’s congressional seats in the May 1841 elections. Strong opposition from the Whigs to the scheme, however, forced Democrats to set a public referendum on the legislation the following August, and Alabamians voted down the general ticket. Frustrated in this attempt to maintain political dominance, Alabama Democrats next created a plan for electoral representation known as the “white basis.” It specified that only the white population would count in voting for state offices, despite the fact that the federal government had established state representation in Congress based upon both the black and white populations, with blacks counted as three-fifths of a white person. Since Whig strength was greatest in areas of the state that had large enslaved populations, that party’s representation was reduced. To ensure their dominance, Democrats also adjusted district boundaries in the legislative session of 1842–43 to favor their candidates. Their efforts were successful and, despite repeated efforts by the Whigs to repeal it, the white-basis system continued until the Civil War.

In the mid-1840s, Alabama Whigs were buffeted by national party differences between now-Sen. Henry Clay and Pres. John Tyler. Despite his affiliation with the Whig Party, Tyler did not automatically approve Whig legislative initiatives. The president also defied the Whigs over their opposition to the annexation of Texas. Competing anti-immigrant and antislavery groups and the victory of pro-expansion Democrat James K. Polk in the presidential race of 1844 caused additional rifts in Whig solidarity. Hurt by electoral restrictions as well, the party was unable to gain a majority in the state legislature during these years, although it maintained electoral clout in the Black Belt region and in the Tennessee Valley. In 1846, however, the party began a comeback and lost the state Senate by a margin of only one the following year. Whig fortunes continued to look brighter later in 1848 when Whig Zachary Taylor earned almost as many votes in Alabama as Democratic candidate Lewis Cass. In the state legislative elections of 1849, the party won a majority of one in the Alabama Senate and reduced the Democratic advantage in the House of Representatives to only eight. Although Alabama Whigs emerged from the electoral contests of 1849 in a strong position, states’ rights and regional issues associated with the Mexican territorial cession and abolition of slavery began to erode their support. Opposition to the expansion of slavery by President Taylor and other northern Whig leaders raised questions among most southern Whigs about the national party’s loyalty to the continuation of that institution.

In 1850 the national battles over slavery in the territories buffeted both Democrats and Whigs. Alabama politics centered on the issue of acceptance or rejection of the Compromise of 1850, which was the attempt by Congress to resolve political differences over the newly acquired Mexican territories. Major issues in this question were the rights of southerners with respect to slavery and infringement on state powers by the federal government. The Democrats in the state split into two factions: Unionists, who supported the compromise, and state’s-rights advocates who wanted to reject it in favor of leaving the Union. Whigs tended to support Unionism, and so helped the pro-Union faction of the Democrats win the governorship and gain a majority in the state legislature. After recovering from the split, however, Democratic legislators turned on the Whigs and once again gerrymandered the electoral districts, further reducing Whig political power in the state.

Alabama Whigs received another blow when the national party selected Winfield Scott as its presidential candidate in the election of 1852. A number of influential southern members believed Scott to be soft on issues affecting the South because he failed to support an act that was passed by Congress to assist southerners with the return of their slaves. When Scott was nominated by the Whigs, those men left the party. Alabamians joined in the defection. Some went over to the Democrats, and others drifted to a new political group, the Know-Nothing or American Party, which was anti-Catholic and anti-immigrant. The national Democratic Party contributed to Whig losses by nominating pro-southern Franklin Pierce for president and Alabamian William R. King for vice president. Pierce, who won the national election, also scored a decisive victory over Scott among Alabama voters.

Alabama Whig fortunes continued to decline when Democrat John Winston easily took the governor’s office in the state election of 1853. His party was victorious in other state races, as well. Whigs subsequently unsuccessfully attempted to repeal the white-basis system, and their numbers fell further during a national controversy over a proposal to acquire Cuba from Spain, which could then have been divided into several new slave states. This battle was followed by the Kansas-Nebraska dispute over slavery in newly created territories in the West. Alabama Whigs were embarrassed by the antislavery stand of the national party and lost more members to the Democrats, who favored allowing slavery to expand into the territories. The Republican Party, which also opposed slavery in new territories, emerged in the North during this period and caused some Alabama Whigs to conclude that southern unity was more important than party affiliation. They left their party to join with fellow southerners against the northern antislavery Whigs and Republicans.

Preempted by the Democrats and the Know Nothings, Alabama Whigs were further marginalized in the state elections of 1855. When returns verified that a significant number of their members had moved to the Democrats, Whigs made a futile attempt to reorganize. Die-hard members of the party supported presidential candidate Millard Fillmore in the election of 1856, but Democrat James Buchanan won easily in the state. When Buchanan took office, Hilliard and other respected Whig leaders announced their support for him. Meanwhile, the growing conflict over the question of slavery in Kansas attracted even more party members to the Democrats, essentially ending any effectiveness of the Whig Party in Alabama. Attempts to reorganize prior to the Civil War were futile, and the party ceased to exist by the end of the 1850s.

Further Reading

- Alexander, Thomas B., Kit C. Carter, Jack R. Lister, Jerry C. Oldshue, and Winfred G. Sandlin. “Who Were the Alabama Whigs?” Alabama Review 16 (January 1963): 5–19.

- Dorman, Lewy. Party Politics in Alabama from 1850 through 1860. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1995.

- Rogers, William Warren, Jr. “Alabama and the Presidential Election of 1836.” Alabama Review 35 (April 1982): 111–26.