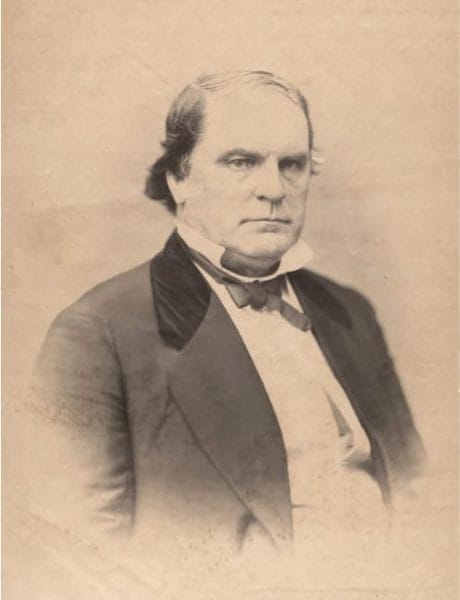

Lewis Eliphalet Parsons (1865)

Lewis Eliphalet Parsons (1817-1895) was an attorney, state legislator, and provisional governor of Alabama during Presidential Reconstruction. He was elected to represent Alabama in the U.S. Senate but was rejected along with representatives of other former Confederate states by the Congress.

Lewis E. Parsons

Lewis Eliphalet Parsons was born on April 28, 1817, in Lisle, New York, the eldest son of Jennett Hepburn and Erastus Bellamy Parsons. His father was a farmer descended from Puritan theologian Jonathan Edwards of Massachusetts. Educated in New York public schools, Parsons read law in New York and Philadelphia. In 1840, he moved to Talladega, Alabama, where he practiced law with future U.S. congressman Alexander White. He married Jane Ann Boyd McCullough Chrisman of Kentucky on September 16, 1841, with whom he had seven children. Active as a Whig and then a Know-Nothing, he was a presidential elector in 1856 for Millard Fillmore. He represented Talladega County in the Alabama House of Representatives from 1859 to 1861 and advocated state aid for internal improvements.

Lewis E. Parsons

Lewis Eliphalet Parsons was born on April 28, 1817, in Lisle, New York, the eldest son of Jennett Hepburn and Erastus Bellamy Parsons. His father was a farmer descended from Puritan theologian Jonathan Edwards of Massachusetts. Educated in New York public schools, Parsons read law in New York and Philadelphia. In 1840, he moved to Talladega, Alabama, where he practiced law with future U.S. congressman Alexander White. He married Jane Ann Boyd McCullough Chrisman of Kentucky on September 16, 1841, with whom he had seven children. Active as a Whig and then a Know-Nothing, he was a presidential elector in 1856 for Millard Fillmore. He represented Talladega County in the Alabama House of Representatives from 1859 to 1861 and advocated state aid for internal improvements.

By 1860, Parsons was a wealthy man in his adopted state, owning $12,000 in real property and $66,000 in personal property, although he owned no slaves. He was also an influential political leader. In 1860, as the secession debate grew, outspoken secessionist William Lowndes Yancey termed Parsons the ablest and most resourceful Unionist debater he ever encountered. Delegates from the Lower South left the 1860 Democratic National Convention to protest the party’s rejection of a pro-slavery platform, raising the threat of secession. Parsons nevertheless believed secession still might be prevented in Alabama. Although two of Parsons’s friends sought to hold former Whigs for the new Constitutional Union Party, Parsons joined the Douglas Democrats. Despite Unionist efforts, Alabama voted to secede from the Union on January 11, 1861.

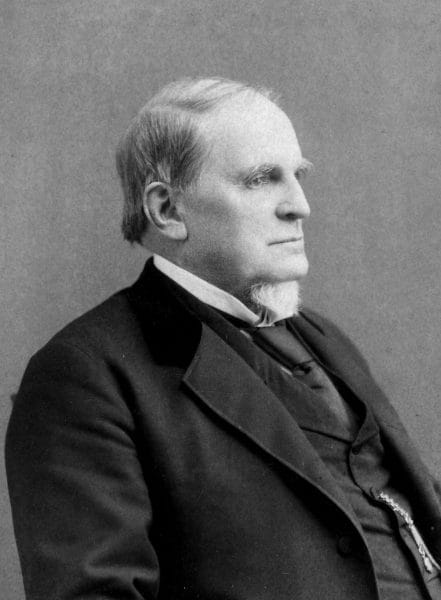

William Lowndes Yancey

During the Civil War many Unionists fled Alabama or served in the Confederate Army, but Parsons continued practicing law in Talladega. As opposition to the Civil War mounted in 1863, Alabama voters chose a governor and legislature who advocated peace. Parsons returned to the Alabama House of Representatives in 1863, where he supported the Confederacy’s use of slaves as soldiers and opposed the state militia system.

William Lowndes Yancey

During the Civil War many Unionists fled Alabama or served in the Confederate Army, but Parsons continued practicing law in Talladega. As opposition to the Civil War mounted in 1863, Alabama voters chose a governor and legislature who advocated peace. Parsons returned to the Alabama House of Representatives in 1863, where he supported the Confederacy’s use of slaves as soldiers and opposed the state militia system.

On May 29, 1865, Pres. Andrew Johnson announced a plan of Reconstruction for the former Confederate states and on June 21 appointed Parsons, a respected, moderate Unionist, as the provisional governor of Alabama. He served until December 20, 1865. Parsons declared in force all Alabama laws enacted before January 11, 1861, except those regarding slavery, and retained in office former Confederate officeholders. Johnson’s plan required prospective voters to swear an amnesty oath to the United States to regain their citizenship, and those disfranchised had to apply for a presidential pardon. As voter registration progressed, Parsons called for an election for delegates to a convention to revise the state constitution. In a proclamation Parsons reminded Alabamians that former slaves were now free and must be governed as free men by Alabama laws.

In a constitutional convention opened on September 12, 1865, representatives abolished slavery, repealed the ordinance of secession, and repudiated the state’s wartime debt without controversy. Disagreements erupted, however, regarding which section of the state would control the legislature. The Black Belt had dominated antebellum state politics through apportionment of the legislature. Now after bitter argument the 1865 convention apportioned representation on the basis of only the white population, giving largely white north Alabama counties control of Reconstruction in Alabama. Years later Parsons reflected that he had “committed a great error” in not urging the convention to adopt qualified black suffrage. Had that step been taken, he believed that Alabama would have been recognized as a state and admitted to representation in Congress in 1865 or 1866, avoiding later Reconstruction turmoil. The convention adopted the revised constitution by proclamation and set an election for governor, legislature, and congressmen for November. In December the legislature elected Parsons to the U.S. Senate, but Congress rejected southern representatives.

After leaving office, Parsons resumed his Talladega law practice and continued to be politically influential. In 1866 he was a delegate to the National Union Convention to mobilize support for Johnson’s conservative approach to Reconstruction. In September 1867, the Democratic and Conservative Party was organized in Alabama; Parsons joined and became a party leader and in 1868 led the Alabama delegation to the Democratic National Convention.

Lewis E. Parsons

In early 1867 Congress passed three Reconstruction Acts, assuming control of Reconstruction and abolishing governments established under Presidential Reconstruction. A new constitutional convention met on November 5, 1867, and revised the state constitution. Blacks were now enfranchised, and significant numbers of whites were disfranchised with no pardon available. The convention also reapportioned the state legislature, basing representation on the whole population and returning legislative dominance to the Black Belt. The Alabama Democratic and Conservative Party opposed ratification of the proposed new constitution. Parsons devised a plan by which white conservatives would boycott the election and the Ku Klux Klan would be dispatched to intimidate blacks from voting, thus ensuring that the constitution would not receive the majority necessary for ratification. The plan worked, delaying Alabama’s readmission to the Union until July 1868.

Lewis E. Parsons

In early 1867 Congress passed three Reconstruction Acts, assuming control of Reconstruction and abolishing governments established under Presidential Reconstruction. A new constitutional convention met on November 5, 1867, and revised the state constitution. Blacks were now enfranchised, and significant numbers of whites were disfranchised with no pardon available. The convention also reapportioned the state legislature, basing representation on the whole population and returning legislative dominance to the Black Belt. The Alabama Democratic and Conservative Party opposed ratification of the proposed new constitution. Parsons devised a plan by which white conservatives would boycott the election and the Ku Klux Klan would be dispatched to intimidate blacks from voting, thus ensuring that the constitution would not receive the majority necessary for ratification. The plan worked, delaying Alabama’s readmission to the Union until July 1868.

The November 1868 Republican victory convinced Parsons that further opposition to Congressional Reconstruction was futile. He stunned contemporaries by defecting to the Republicans in September 1869. He later explained his actions, saying the 1868 election had ensured Republican control of the presidency and the Congress for the next four years. Having opposed Republicans “as long as it was worth while,” Parsons believed it “would be better to make terms with them,” work with them, and “acquire their confidence.”

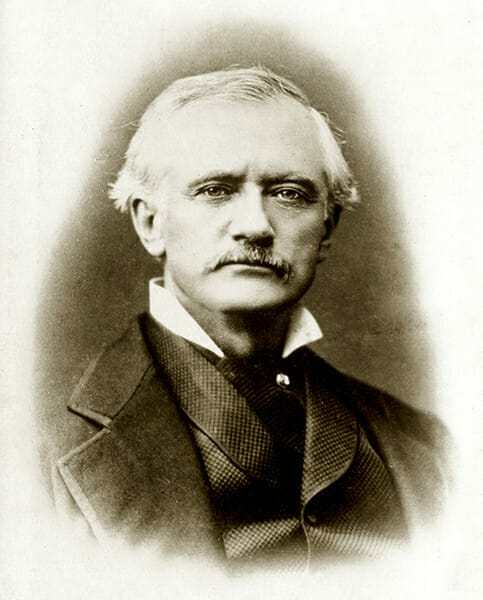

John Tyler Morgan

Parsons became a leader among the native white southern element of the Republican Party (known as scalawags) and became embroiled in party power struggles. He returned to the Alabama House of Representatives (1872-1874), where he served as speaker and assisted in killing proposed civil rights bills. In 1872, 1876, and 1880 Parsons was nominated as a Republican presidential elector and in 1872 was a delegate to the National Republican Convention, where he chaired the convention’s platform committee. He favored moderation on civil rights and a moderate, white-dominated Republican Party.

John Tyler Morgan

Parsons became a leader among the native white southern element of the Republican Party (known as scalawags) and became embroiled in party power struggles. He returned to the Alabama House of Representatives (1872-1874), where he served as speaker and assisted in killing proposed civil rights bills. In 1872, 1876, and 1880 Parsons was nominated as a Republican presidential elector and in 1872 was a delegate to the National Republican Convention, where he chaired the convention’s platform committee. He favored moderation on civil rights and a moderate, white-dominated Republican Party.

After Democrats swept the 1874 elections in Alabama, Parsons continued as an active Republican while many other Alabama scalawags rejoined the Democrats. His nomination in 1877 as U.S. District Attorney for the Northern District of Alabama provoked a storm of opposition from political enemies. He held this office while awaiting confirmation from the U.S. Senate. Despite numerous endorsements, including a strong public recommendation from Alabama’s U.S. senator John Tyler Morgan, a Democrat, the Senate rejected his nomination in March 1878. His political career now ended, Parsons returned to Talladega, where he practiced law until his death on June 8, 1895.

Note: This entry was adapted with permission from Alabama Governors: A Political History of the State, edited by Samuel L. Webb and Margaret Armbrester (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001).

Further Reading

- Parsons, Henry. Parsons Family Descendants of Comet Joseph Parsons. Springfield, 1636-Northhampton, 1655. N.p., 1912

- Wiggins, Sarah Woolfolk. The Scalawag in Alabama Politics, 1865-1881. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1977.