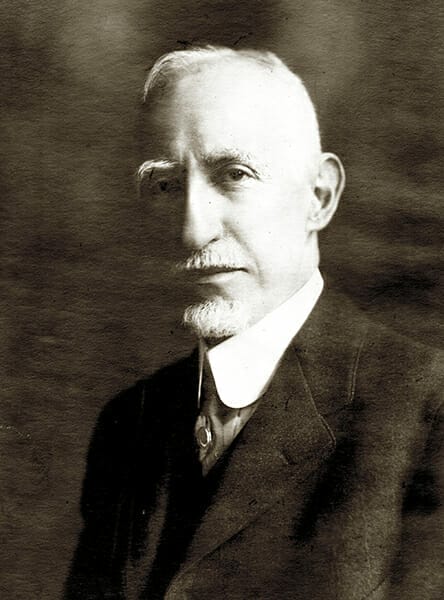

Erwin Craighead

Erwin Craighead

Erwin Craighead (1852-1932) was editor of the Mobile Register for more than 40 years and was one of the most influential journalists of the New South Era. His incisive articles and editorials touting Progressivism were reprinted across the region and the nation. Upon his retirement in 1927, the New York Times hailed Craighead as one of the most scholarly newspapermen and forceful editors of the South. A relentless civic booster, he promoted Mobile as a diverse city of thriving commerce and venerable tradition.

Erwin Craighead

Erwin Craighead (1852-1932) was editor of the Mobile Register for more than 40 years and was one of the most influential journalists of the New South Era. His incisive articles and editorials touting Progressivism were reprinted across the region and the nation. Upon his retirement in 1927, the New York Times hailed Craighead as one of the most scholarly newspapermen and forceful editors of the South. A relentless civic booster, he promoted Mobile as a diverse city of thriving commerce and venerable tradition.

Moved by the ideals of the Progressive Era, Craighead championed various political and social reforms, including the commission form of municipal government, women’s voting rights, increased funding for public education and public infrastructure, and improved living conditions for urban dwellers. Craighead’s racial views were sympathetic to African Americans, and he refrained from the race-baiting that was characteristic of many other southern writers after 1900. But like his fellow progressive southerners, Craighead’s writings on race are distinctly paternalistic toward African Americans. Race was only one of Craighead’s many editorial concerns over the years, however. He wrote well-crafted treatises on politics, religion, wars, diplomacy, education, trade, hurricanes, and hundreds of other topics, but always with a steadfast focus on Mobile and its future as a city of the New South.

Craighead was born in Nashville, Tennessee, on April 4, 1852, the son of James Brown Craighead, an attorney, and Ellen Kirkman Erwin. The Craighead family included lawyers, planters, and clergymen who left North Carolina for Nashville in the early nineteenth century. Craighead’s great-grandfather, Thomas B. Craighead, served as the first pastor of Nashville’s First Presbyterian Church. A friend of Andrew Jackson’s, the Reverend Craighead organized Nashville’s relief effort for the survivors of the Fort Mims Massacre during the Creek War of 1813-14.

Lura Craighead

The Civil War and Reconstruction had a lasting impact on the young Craighead and deeply influenced his later writing. He attended private and public schools in Nashville and, from 1866 to 1868, studied at the Grammar School of Racine College in Wisconsin. At age 16 he returned to his hometown and studied law at Nashville College (now Peabody College of Education and Human Development at Vanderbilt University), where he first forayed into journalism. He earned a bachelor’s degree in literature in 1872. Craighead then went to Europe to study law and philosophy in London and Leipzig, Germany, and became fluent in French, German, and Italian. Craighead returned to Nashville in 1877, read law and was admitted to the Tennessee bar, though he did not practice.

Lura Craighead

The Civil War and Reconstruction had a lasting impact on the young Craighead and deeply influenced his later writing. He attended private and public schools in Nashville and, from 1866 to 1868, studied at the Grammar School of Racine College in Wisconsin. At age 16 he returned to his hometown and studied law at Nashville College (now Peabody College of Education and Human Development at Vanderbilt University), where he first forayed into journalism. He earned a bachelor’s degree in literature in 1872. Craighead then went to Europe to study law and philosophy in London and Leipzig, Germany, and became fluent in French, German, and Italian. Craighead returned to Nashville in 1877, read law and was admitted to the Tennessee bar, though he did not practice.

Craighead settled in New Orleans in 1878 and became a staff writer for the New Orleans Times. He married Lura Harris of Nashville on December 12, 1878, and had one son, Frank, who was born on November 23, 1879. In 1880 he used an inheritance to purchase a half-ownership in the New Orleans Daily States and served as its managing editor for two years. During his time in New Orleans, Craighead polished his writing skills and acquired a deep knowledge of Gulf Coast history, politics, society, and culture. In 1882 Thomas Rapier, editor of the New Orleans Times, recommended Craighead to his brother John for a position with the Mobile Register. Craighead became city editor and was promoted to managing editor in 1884 and became editor and vice president in 1893. Although Craighead was many years Rapier’s junior, the two men agreed on most issues. Rapier and his wife introduced Erwin and Lura Craighead to Mobile’s elite, including the most prominent Mardi Gras mystic societies. Craighead actively promoted the Mobile Symphony and joined the Iberville Historical Society, whose membership included noted historian Peter Joseph Hamilton.

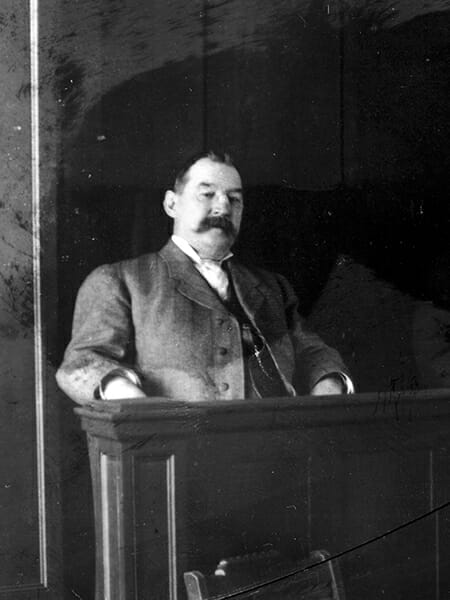

Patrick J. Lyons

Craighead’s reputation as “Mobile’s newspaperman” granted him full access to educators, clergymen, and local and state officials. He befriended key leaders of Mobile’s powerful Democratic machine during the 1890s, most notably councilman and wholesale grocer Patrick J. Lyons, who became mayor in 1904. Through Lyons and his associates, Craighead gained an intimate understanding of the inner workings of Mobile’s aldermanic government, which consisted of a mayor and a city council made up of elected aldermen and councilmen. The mayor oversaw the duties of the city council and the various municipal departments, such as public works and public safety. To Craighead and other progressives, this form of government was more open to corruption and political favoritism than the commission form, in which the managerial duties and appointments for the various departments were shared by three elected officials rather than by a single mayor. Craighead thus lent his staunch editorial support to the adoption of commission government in Mobile in 1911. Mayor Lyons, who initially built his political hegemony under the city’s particular brand of aldermanic governance, in 1911 became one of Mobile’s three commissioners due in no small part to Craighead’s friendship and editorial support.

Patrick J. Lyons

Craighead’s reputation as “Mobile’s newspaperman” granted him full access to educators, clergymen, and local and state officials. He befriended key leaders of Mobile’s powerful Democratic machine during the 1890s, most notably councilman and wholesale grocer Patrick J. Lyons, who became mayor in 1904. Through Lyons and his associates, Craighead gained an intimate understanding of the inner workings of Mobile’s aldermanic government, which consisted of a mayor and a city council made up of elected aldermen and councilmen. The mayor oversaw the duties of the city council and the various municipal departments, such as public works and public safety. To Craighead and other progressives, this form of government was more open to corruption and political favoritism than the commission form, in which the managerial duties and appointments for the various departments were shared by three elected officials rather than by a single mayor. Craighead thus lent his staunch editorial support to the adoption of commission government in Mobile in 1911. Mayor Lyons, who initially built his political hegemony under the city’s particular brand of aldermanic governance, in 1911 became one of Mobile’s three commissioners due in no small part to Craighead’s friendship and editorial support.

During the run-up to the Spanish-American War, Craighead opposed any military action, agonizing in editorials about the possible negative impact of war on the South’s sluggish recovery from the economic depression following the Panic of 1893. Craighead eventually saw war with Spain as a means of expanding U.S. influence in Cuba, the Caribbean, and Latin America and thus diversifying Mobile’s commercial role throughout these areas. This radical shift from isolationism to imperialism during the late 1890s logically evolved from Craighead’s desire that the South rejoin the nation and from his dedication to Mobile’s business interests

Mardi Gras King and Queen

Craighead solidified his alignment with the city’s prominent businessmen after 1900 with his public criticism of prohibition. In addition to being a proponent of Mobile’s European flavor, he fully understood that any state or federal regulation of saloons would be detrimental to tourism, especially during Mardi Gras. Craighead also editorialized against attempts by state officials to ban Sunday baseball, vaudeville, and movies. During debates over moral reforms such as Sunday “blue laws” and prohibition, Craighead presented his remarks as arguments in favor of Home Rule. In reality he believed that what was good for business was good for Mobile, and he seldom deviated from this position.

Mardi Gras King and Queen

Craighead solidified his alignment with the city’s prominent businessmen after 1900 with his public criticism of prohibition. In addition to being a proponent of Mobile’s European flavor, he fully understood that any state or federal regulation of saloons would be detrimental to tourism, especially during Mardi Gras. Craighead also editorialized against attempts by state officials to ban Sunday baseball, vaudeville, and movies. During debates over moral reforms such as Sunday “blue laws” and prohibition, Craighead presented his remarks as arguments in favor of Home Rule. In reality he believed that what was good for business was good for Mobile, and he seldom deviated from this position.

Such editorial stands often brought him into direct conflict with moralistic reformers such as Gov. Braxton B. Comer. But Craighead and Comer generally agreed on educational reform measures, especially the need for increased state funding for public schools. Lura Craighead, also an advocate for educational reform, influenced Erwin’s views on education, woman suffrage, child labor laws, and other social and political reforms. Erwin Craighead actively participated in several conferences on southern education, and in 1911 Governor Comer appointed him as a trustee for the state normal schools (white teachers colleges).

For Craighead and other southern progressives, racial issues were probably the most torturous that they confronted. The Mobile Register was a beacon of racial moderation in comparison with Mobile’s other white-owned newspapers, such as the Daily Herald. Yet, the paternalistic Craighead, whom African American leaders respected because of his editorial restraint on racial matters, often appeared to be ill-informed or ambivalent about the plight of black Mobilians. During a brief boycott by blacks of segregated streetcars in 1902, Craighead questioned the motives of the African American preachers who allegedly had instigated the protest and labeled their followers “child-like,” and he avoided any discussion of possible grievances. As a confirmed business supporter, his sympathies lay with the streetcar company’s owner and employees, not with the boycotters. On July 4, 1904, a segregationist U.S. customs collector expelled blacks from Bienville Square, Mobile’s largest public park, even though the park had been open to blacks and whites for generations. Craighead remained silent. In the autumn of 1906, two young black men died at the hands of a lynch mob at Magazine Point. Craighead merely expressed his relief that the murders had occurred outside the city limits, primarily concerned about the incident’s negative effect on the city’s image.

Braxton Bragg Comer

In January 1909 an armed mob removed a black prisoner from the county jail and lynched him near Christ Episcopal Church. The black victim was accused of mortally wounding a popular white deputy sheriff, and all evidence revealed that the county sheriff and his jailer actively participated in the lynching. These circumstances led Craighead to condemn the lynching on strict legal grounds. In this particular instance, Craighead’s convoluted legalistic argument may have comforted his white readers who shared his worries about law and order and the increasing frequency of racial violence. Moreover, this viewpoint diverted attention away from the actual victims of mob violence to a philosophical discussion of the law and civic responsibilities.

Braxton Bragg Comer

In January 1909 an armed mob removed a black prisoner from the county jail and lynched him near Christ Episcopal Church. The black victim was accused of mortally wounding a popular white deputy sheriff, and all evidence revealed that the county sheriff and his jailer actively participated in the lynching. These circumstances led Craighead to condemn the lynching on strict legal grounds. In this particular instance, Craighead’s convoluted legalistic argument may have comforted his white readers who shared his worries about law and order and the increasing frequency of racial violence. Moreover, this viewpoint diverted attention away from the actual victims of mob violence to a philosophical discussion of the law and civic responsibilities.

Late in his career, Craighead wrote several articles and two books that focused on Mobile’s history and recollections of his own life. In 1925 he published From Mobile’s Past: Sketches of Memorable People and Events, followed in 1930 by Mobile: Fact and Tradition, Noteworthy People and Events. His last major project was “Dropped Stitches from Mobile’s Past,” a series of historical sketches and essays published in the Mobile Register during 1931 and 1932.

Craighead died on February 3, 1932, in Mobile, his beloved, adopted hometown. He served as Mobile’s principal journalistic voice and conscience for more than 40 years. During the course of his career, the Mobile Register became one of the region’s most vocal champions of Henry W. Grady’s vision of the New South and his belief in the need for sectional reconciliation and economic renaissance.

Additional Resources

Alsobrook, David E. “Alabama’s Port City: Mobile during the Progressive era, 1896–1917.” Ph.D. diss., Auburn University, 1983.

Craighead, Erwin. Biographical File (Microfilm copy). Alabama Department of Archives and History, Montgomery.

McWilliams, Tennant S. The New South Faces the World: Foreign Affairs and the Southern Sense of Self, 1877–1950. Baton Rouge, La.: LSU Press, 1988.

Nelson, Lucy. “Erwin Craighead.” Turn of the Century Mobile: People and Places. Mobile, Ala.: Southern Lithographing Co., 1971, pp. 91–93.