Yuchis in Alabama

The Yuchis are a Native American tribe who resided in present-day Alabama until the early 1830s, when they were forcibly removed to Indian Territory (now eastern Oklahoma). Allied at various times and to varying degrees with the Creeks, they played a role in the Creek War of 1813-14, the Seminole wars, and the American Revolution. Today, they continue their traditions in Oklahoma and seek federal recognition as a culturally autonomous society.

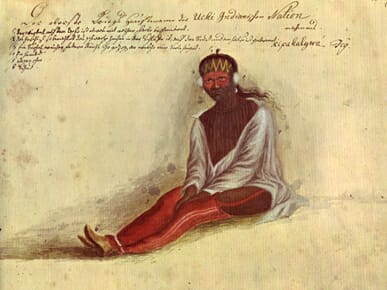

Senkaitschi, Yuchi Leader

According to their oral tradition, the Yuchis were created by the Sun, a visible manifestation of the Creator, and the first Yuchi man was Tsoyaha, meaning “Offspring of the Sun.” Tsoyaha is also the Yuchi name for themselves as a tribe. The Yuchis speak a language that is not closely related to any known language. Little is known about the Yuchis at the time of their first encounter with Europeans. In 1567, Spanish explorer Juan Pardo noted the existence of a group whom he identified alternatively as “Uchi” and “Huchi,” although his reasons for this remain unclear. These were likely the Yuchis, who at the time resided somewhere in what is today eastern Tennessee.

Senkaitschi, Yuchi Leader

According to their oral tradition, the Yuchis were created by the Sun, a visible manifestation of the Creator, and the first Yuchi man was Tsoyaha, meaning “Offspring of the Sun.” Tsoyaha is also the Yuchi name for themselves as a tribe. The Yuchis speak a language that is not closely related to any known language. Little is known about the Yuchis at the time of their first encounter with Europeans. In 1567, Spanish explorer Juan Pardo noted the existence of a group whom he identified alternatively as “Uchi” and “Huchi,” although his reasons for this remain unclear. These were likely the Yuchis, who at the time resided somewhere in what is today eastern Tennessee.

By the end of the seventeenth century, the Yuchis become more clearly identifiable in the documentary record. In this period, they appear to have resided in a wide range of locales across the Southeast, with the center of gravity of Yuchi life shifting south and east toward the English settlements in South Carolina and, after its founding, Georgia.

During the first half of the eighteenth century, the Yuchis inhabited several towns on the Savannah River. As Georgia settlers expanded westward, the residents of these Yuchi towns largely consolidated with those in Yuchi Town on the Chattahoochee River. Located in what is now Russell County, Alabama, Yuchi Town was one of a number of Indian towns near modern-day Fort Moore (formerly Fort Benning) and was occupied through the time of removal to Indian Territory. Some Yuchis also resided among the Upper Creek towns in north-central Alabama.

Kipahalgwa

According to historical accounts, Yuchi traditional culture centered on the town as the basic social group. Yuchi towns possessed a town square, where public rituals were practiced, and each was led by a hereditary chief. The most important of these rituals was the Green Corn Ceremony, an annual harvest ritual that was practiced in varied forms by most Southeastern tribes. These structures and town rituals continue to characterize Yuchi life today.

Kipahalgwa

According to historical accounts, Yuchi traditional culture centered on the town as the basic social group. Yuchi towns possessed a town square, where public rituals were practiced, and each was led by a hereditary chief. The most important of these rituals was the Green Corn Ceremony, an annual harvest ritual that was practiced in varied forms by most Southeastern tribes. These structures and town rituals continue to characterize Yuchi life today.

The majority of Yuchi people resided among the Lower Creeks and were associated with Yuchi Town, although they remained generally independent of the Creek political structure. The traditional origin stories describing Yuchi creation, their language, and most importantly their ceremonies are markedly different from those of the Creeks. Their cultural beliefs and practices are distinct, but they do show evidence of influence by the Shawnee and other peoples of the upper Midwest, with whom the Yuchis were in contact. Socially, the Yuchis shared with other southeastern groups strong emphasis on the town as a basic social unit, but they were unique in tracing descent through the father, rather than the mother, and in their social divisions. Despite their cultural differences, however, the Yuchis and the Creeks shared similar tools, architecture, and economic practices. These included corn horticulture, participation in the deerskin trade (later replaced by animal husbandry), and wooden houses constructed of wattle and daub, which was later replaced by log-timber construction. Both groups relied to an ever-expanding degree on European trade goods, including finished clothing, trade cloth and notions, and metal tools.

Despite their social, cultural, and political independence, during the period after the American Revolution the Yuchis came to be treated by the U.S. government and by Creek political leaders as a constituent part of the Creek Nation. The historical record documents ongoing efforts by the Yuchis to maintain and assert their autonomy; at times these efforts included open conflict with their Creek neighbors. The anti-Yuchi sentiment of some Creek political leaders is also well documented.

Timpoochee Barnard

Some Yuchis joined culturally conservative Creek peoples and relocated to Florida, where they joined with Indians from other tribes to form the multi-ethnic Seminole society. Many of the Indians who came together shared a commitment to local town autonomy, an opposition to American interference in Indian life and land ownership, an adherence to traditional religion and customs, and an economic system based on traditional subsistence farming, hunting, and the deerskin trade. The social complexities of this period reflect older patterns of tribal conflict that continue into the present and that have roots in prehistory.

Timpoochee Barnard

Some Yuchis joined culturally conservative Creek peoples and relocated to Florida, where they joined with Indians from other tribes to form the multi-ethnic Seminole society. Many of the Indians who came together shared a commitment to local town autonomy, an opposition to American interference in Indian life and land ownership, an adherence to traditional religion and customs, and an economic system based on traditional subsistence farming, hunting, and the deerskin trade. The social complexities of this period reflect older patterns of tribal conflict that continue into the present and that have roots in prehistory.

Yuchi forces fought for both sides during the Creek Civil War and the Second Seminole War (1835-1842) and served with the U.S. government in a number of battles under leader Timpoochee Barnard. Barnard, the son of a Yuchi woman and Timothy Barnard, a trader and deputy to Indian agent Benjamin Hawkins, was the most prominent Yuchi figure of the era.

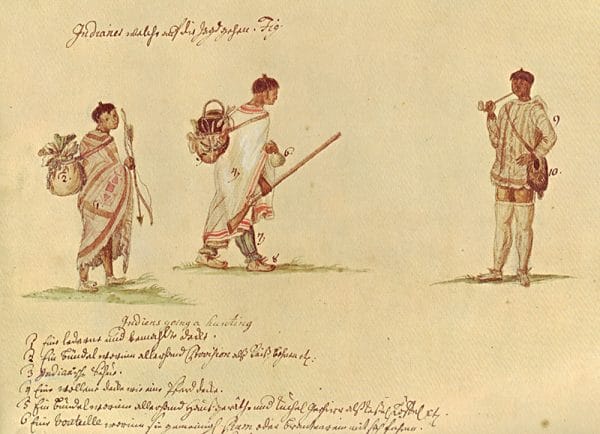

Yuchis Going Hunting

The events of the Creek War and the First and Second Seminole Wars, compounded by ever-increasing demands for Indian lands by white settlers, led the U.S. government to draft a plan to remove all of the Indians in the Southeast to Indian Territory (now Oklahoma). The Yuchis were active in resistance to Pres. Andrew Jackson’s policy of Indian removal, but most Yuchis accompanied their Creek neighbors west to Indian Territory in 1836. In their new home, towns once again were the focus of Yuchi life. The most important present-day Yuchi towns in Oklahoma are Duck Creek Town, near the modern municipality of Bixby, Polecat Town, near the city of Sapulpa, and Sand Creek Town, near present-day Bristow.

Yuchis Going Hunting

The events of the Creek War and the First and Second Seminole Wars, compounded by ever-increasing demands for Indian lands by white settlers, led the U.S. government to draft a plan to remove all of the Indians in the Southeast to Indian Territory (now Oklahoma). The Yuchis were active in resistance to Pres. Andrew Jackson’s policy of Indian removal, but most Yuchis accompanied their Creek neighbors west to Indian Territory in 1836. In their new home, towns once again were the focus of Yuchi life. The most important present-day Yuchi towns in Oklahoma are Duck Creek Town, near the modern municipality of Bixby, Polecat Town, near the city of Sapulpa, and Sand Creek Town, near present-day Bristow.

After Oklahoma’s statehood, the Yuchis were recognized as a single town in the Creek national government and sent representatives to the Creek national council. Throughout the changes wrought by the dissolution of the Creek Nation (ca. 1907) and the revival of its government in the late twentieth century, the Yuchis have lacked any direct voice in the governance of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation. The Yuchis have continually sought ways to increase their communal autonomy and are presently seeking separate federal acknowledgement. Yuchi people regularly make trips to sites in Georgia and Alabama seeking to connect to their ancient homelands.

Further Reading

- Ethridge, Robbie Franklyn. Creek Country: The Creek Indians and Their World. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003.

- Jackson, Jason Baird. Yuchi Ceremonial Life: Performance, Meaning and Tradition in a Contemporary American Indian Community. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2003.

- ———. “Yuchi.” In Handbook of North American Indians. Vol. 14, Southeast. Edited by William C. Sturtevant and Raymond Fogelson. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 2004.

- Speck, Frank G. Ethnology of the Yuchi Indians. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2004.