William Bartram

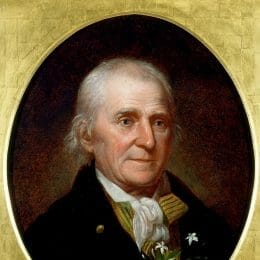

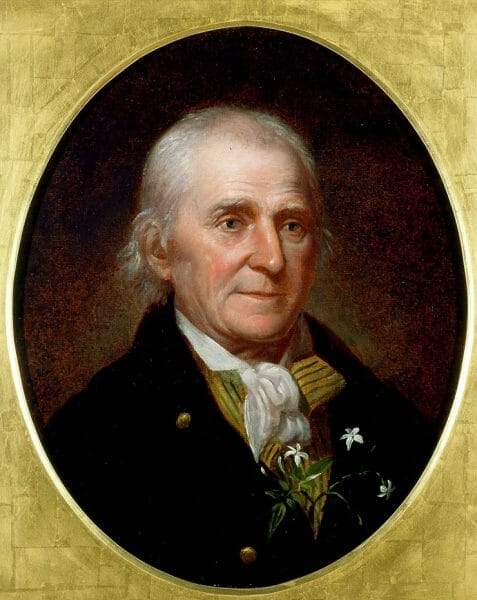

William Bartram

The fame of naturalist, nurseryman, artist, and author William Bartram (1739-1823) rests primarily on his one book, Travels through North and South Carolina, East and West Florida, the Cherokee Country, the Extensive Territories of the Muscolgulges, or Creek Confederacy, and the Country of the Chactaws [sic] (1791). This literary and scientific classic describes his journey through southeastern North America during the Revolutionary War era. It is an essential resource on the flora and fauna of the Southeast and includes detailed descriptions of his visits among the Indian peoples of the region, including what is now Alabama. Bartram’s imagery inspired such poets as Samuel Taylor Coleridge and William Wordsworth, and Travels is recognized as the first classic of environmental literature written and published in the United States.

William Bartram

The fame of naturalist, nurseryman, artist, and author William Bartram (1739-1823) rests primarily on his one book, Travels through North and South Carolina, East and West Florida, the Cherokee Country, the Extensive Territories of the Muscolgulges, or Creek Confederacy, and the Country of the Chactaws [sic] (1791). This literary and scientific classic describes his journey through southeastern North America during the Revolutionary War era. It is an essential resource on the flora and fauna of the Southeast and includes detailed descriptions of his visits among the Indian peoples of the region, including what is now Alabama. Bartram’s imagery inspired such poets as Samuel Taylor Coleridge and William Wordsworth, and Travels is recognized as the first classic of environmental literature written and published in the United States.

Franklinia altamaha

William Bartram and his twin sister Elizabeth were born on April 9, 1739, (although there is some confusion about this date) in Kingsessing (now within the city of Philadelphia), Pennsylvania, to world-renowned botanist John Bartram and his second wife, Anne Mendenhall. Bartram showed a talent for illustration early on and was raised among of his father’s prominent intellectual friends and correspondents, including Benjamin Franklin (for whom he named the Franklinia altamaha tree)and Carl von Linné (popularly known as Linnaeus). John included the teen-aged Billy, as he was known to the family, on plant-gathering expeditions and mailed his son’s drawings to eminent naturalists in Europe. William attended Philadelphia Academy (later the University of Pennsylvania) for three years but failed to translate his education and talents into an income-yielding profession. After a three-year apprenticeship as a trader, Billy moved to the Cape Fear region of coastal North Carolina, where he lived with his uncle William Bartram and sought to establish himself in that profession.

Franklinia altamaha

William Bartram and his twin sister Elizabeth were born on April 9, 1739, (although there is some confusion about this date) in Kingsessing (now within the city of Philadelphia), Pennsylvania, to world-renowned botanist John Bartram and his second wife, Anne Mendenhall. Bartram showed a talent for illustration early on and was raised among of his father’s prominent intellectual friends and correspondents, including Benjamin Franklin (for whom he named the Franklinia altamaha tree)and Carl von Linné (popularly known as Linnaeus). John included the teen-aged Billy, as he was known to the family, on plant-gathering expeditions and mailed his son’s drawings to eminent naturalists in Europe. William attended Philadelphia Academy (later the University of Pennsylvania) for three years but failed to translate his education and talents into an income-yielding profession. After a three-year apprenticeship as a trader, Billy moved to the Cape Fear region of coastal North Carolina, where he lived with his uncle William Bartram and sought to establish himself in that profession.

Purple Finch

Bartram’s life changed in 1765 when his father, John, was appointed by King George III to explore the territory of Florida as an official botanist. In 1766, John returned to Philadelphia, but William remained in Florida and purchased a plantation near the St. Johns River near present-day Jacksonville. He was an utter failure as a planter and may have taken a position with British surveyor general William Gerard De Brahm, who was mapping the new Florida territory. After surviving a shipwreck off the Atlantic coast of Florida, Bartram returned to Philadelphia. Credit problems forced him to leave in 1770, however, and the following year, he moved to St. Augustine.

Purple Finch

Bartram’s life changed in 1765 when his father, John, was appointed by King George III to explore the territory of Florida as an official botanist. In 1766, John returned to Philadelphia, but William remained in Florida and purchased a plantation near the St. Johns River near present-day Jacksonville. He was an utter failure as a planter and may have taken a position with British surveyor general William Gerard De Brahm, who was mapping the new Florida territory. After surviving a shipwreck off the Atlantic coast of Florida, Bartram returned to Philadelphia. Credit problems forced him to leave in 1770, however, and the following year, he moved to St. Augustine.

Although these were turbulent times for Bartram, he made artistic strides in depicting the native plants of his new home region, many of which remained unknown to Western science. William found an audience for his work among his father’s connections in Europe. Drawings that he sent to London cloth merchant and botany enthusiast Peter Collinson in 1772 brought commissions from London physician John Fothergill (for whom the North American plant genus Fothergilla is named), as well as noted shell collector Margaret Harley Cavendish Bentinck, Duchess of Portland.

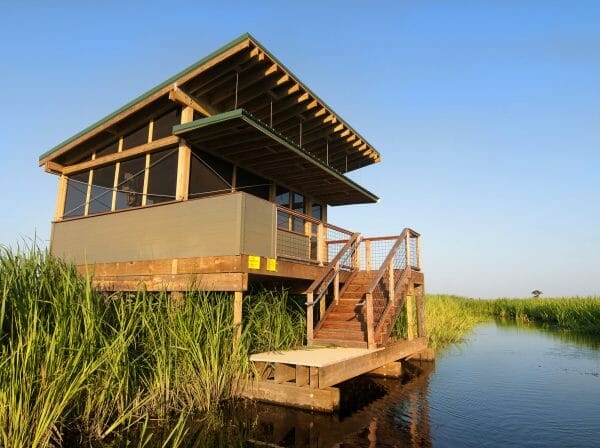

Fothergill hired Bartram to collect and sketch more plants, and Bartram departed for Charleston in March 1773, thus beginning what would become his famous travels. His path ranged through the Georgia and South Carolina Piedmont to the Atlantic barrier islands off Georgia to the upper waters of the St. Johns River and across the Florida peninsula. In late 1774, Bartram journeyed through Cherokee territory and then southwest through the Creek and Choctaw territories to the Mississippi River. During the 1775–76 leg of his journey, along what later became the Federal Road, Bartram passed through Alabama’s present-day Russell and Macon counties to the future site of Montgomery and then turned southwest through what are now Lowndes, Butler, Conecuh, Escambia, and Baldwin counties. Bartram reached Mobile in July 1775 and sailed up the Tensaw and Tombigbee rivers on a route now called the Bartram Canoe Trail. At the Mobile Delta, Bartram saw his first evening primrose (Oenothera grandiflora), which he sketched and described as “the most brilliant shew [show] of any yet known to exist.”

Bartram Biodiversity Scene

After a brief skirmish in the Revolutionary War, about which details are sparse, Bartram returned to Philadelphia on January 2, 1777. Friends had given him up for dead at least once. The trip made Bartram’s reputation as an expert in natural history and Native American cultures, and it also helped the Bartram family’s nursery business. John Bartram died in 1777, leaving the garden to son John Bartram Jr., and William joined his brother in running the operation, preparing orders for such important figures as George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and author Hector St. John de Crèvecoeur. In 1786, Bartram fell from a cypress tree while gathering seeds, broke his leg, and may have spent his recuperation working on the manuscript for Travels. Because the book evolved slowly and was intended to serve many purposes, it can strike modern readers as uneven. It is perhaps best read in small sections or as a reference for specific flora, fauna, peoples, or locales. The introduction offers an excellent example of Enlightenment-era nature writing. Part one includes a detailed account of the 1773 Treaty of Augusta, in which the Cherokees suffered the “humiliating lash” of a Creek cession of their land taken in warfare. Part two contains the book’s most memorable scenes, including a clash with “crocodiles” on the St. Johns River. Parts three and four (the latter presented in typical eighteenth-century ethnography form) include astute observations of Creek, Cherokee, and Choctaw customs and culture in remarkably unbiased accounts that historians continue to use.

Bartram Biodiversity Scene

After a brief skirmish in the Revolutionary War, about which details are sparse, Bartram returned to Philadelphia on January 2, 1777. Friends had given him up for dead at least once. The trip made Bartram’s reputation as an expert in natural history and Native American cultures, and it also helped the Bartram family’s nursery business. John Bartram died in 1777, leaving the garden to son John Bartram Jr., and William joined his brother in running the operation, preparing orders for such important figures as George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and author Hector St. John de Crèvecoeur. In 1786, Bartram fell from a cypress tree while gathering seeds, broke his leg, and may have spent his recuperation working on the manuscript for Travels. Because the book evolved slowly and was intended to serve many purposes, it can strike modern readers as uneven. It is perhaps best read in small sections or as a reference for specific flora, fauna, peoples, or locales. The introduction offers an excellent example of Enlightenment-era nature writing. Part one includes a detailed account of the 1773 Treaty of Augusta, in which the Cherokees suffered the “humiliating lash” of a Creek cession of their land taken in warfare. Part two contains the book’s most memorable scenes, including a clash with “crocodiles” on the St. Johns River. Parts three and four (the latter presented in typical eighteenth-century ethnography form) include astute observations of Creek, Cherokee, and Choctaw customs and culture in remarkably unbiased accounts that historians continue to use.

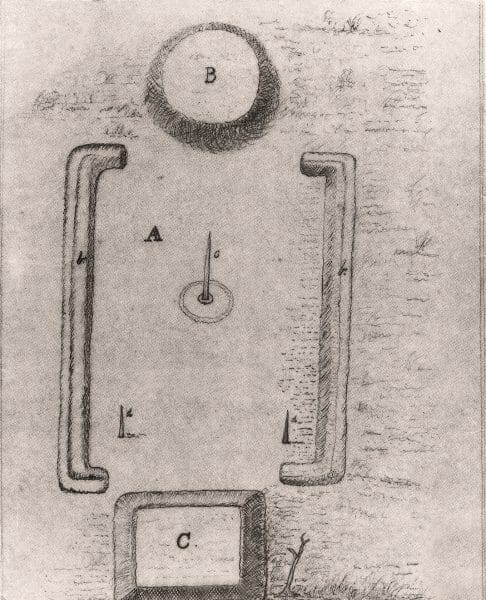

Chunkey Yard

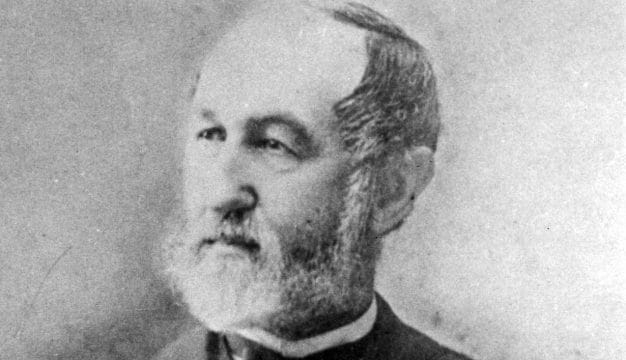

Bartram published only a handful of essays after Travels but remained active in intellectual circles. He collaborated on several projects, most notably with University of Pennsylvania professor Benjamin Smith Barton on a project that eventually became the unpublished manuscript “Observations on the Creek and Cherokee Indians,” Bartram’s most in-depth piece on Native Americans, and Bartram created the illustrations for Barton’s Elements of Botany (1803). Scottish-born ornithologist Alexander Wilson also sought Bartram’s advice and with his help produced the nine-volume American Ornithology (1808–14). The set predated the work of John James Audubon and deserves credit as the first ornithology published in the United States. By guiding and training a new generation of naturalists, William Bartram built upon the legacy of Travels and helped to nurture an environmental tradition that flourishes to this day. Bartram died in his home on July 22, 1823, at the age of 84 and was buried on the family property. The gravesite now lies within the Bartram’s Garden National Historic Landmark in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Chunkey Yard

Bartram published only a handful of essays after Travels but remained active in intellectual circles. He collaborated on several projects, most notably with University of Pennsylvania professor Benjamin Smith Barton on a project that eventually became the unpublished manuscript “Observations on the Creek and Cherokee Indians,” Bartram’s most in-depth piece on Native Americans, and Bartram created the illustrations for Barton’s Elements of Botany (1803). Scottish-born ornithologist Alexander Wilson also sought Bartram’s advice and with his help produced the nine-volume American Ornithology (1808–14). The set predated the work of John James Audubon and deserves credit as the first ornithology published in the United States. By guiding and training a new generation of naturalists, William Bartram built upon the legacy of Travels and helped to nurture an environmental tradition that flourishes to this day. Bartram died in his home on July 22, 1823, at the age of 84 and was buried on the family property. The gravesite now lies within the Bartram’s Garden National Historic Landmark in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Further Reading

- Braund, Kathyrn H., ed. The Attention of a Traveller: Essays on William Bartram’s “Travels” and Legacy. Tuscaloosa, Ala.: University of Alabama Press, 2022.

- Harper, Francis, ed. The Travels of William Bartram: Naturalist Editions. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1998.

- Sanders, Brad. Guide to William Bartram’s Travels: Following the Trail of America’s First Great Naturalist. Athens, Ga.: Fevertree Press, 2002.

- Slaughter, Thomas P. ed. William Bartram: Travels and Other Writings. New York: Library of America, 1996.

- ———. The Natures of John and William Bartram. New York: Vintage, 1996.

- Waselkov, Gregory A., and Kathryn E. Holland Braund. William Bartram on the Southeastern Indians. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1995.