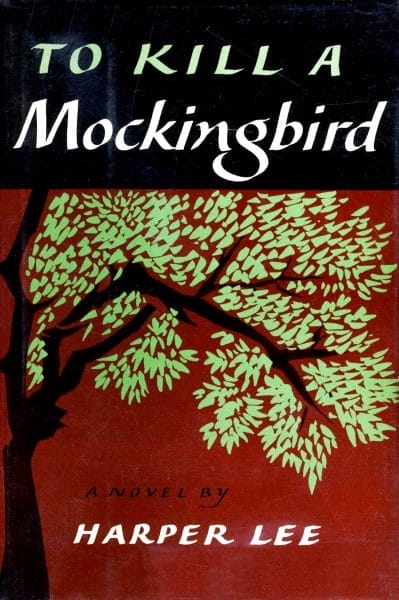

To Kill A Mockingbird

By almost any measurement, Harper Lee‘s To Kill A Mockingbird (1960) is the most important novel ever authored by a native Alabamian. The Pulitzer Prize–winning novel spent 88 weeks on bestseller lists, and by the 50th anniversary of its publication in 2010 had sold some 40 million copies. It continues to sell around a million copies a year and is often ranked among the world’s best-sellers. The themes and issues raised in the novel remain relevant, and thus To Kill A Mockingbird will likely hold its place in public discourse on tolerance, justice, and humanity.

To Kill A Mockingbird

The story told in the novel parallels two court cases that took place in Alabama but was not based directly on them: The Scottsboro Trials of 1931, in which nine black youths were tried for allegedly raping two white women on a train in north Alabama; and a November 1933 incident in Monroeville in which Naomi Lowery, a poor white woman, alleged that Walter Lett, a black ex-convict, sexually assaulted her. Lee began work on what would become the novel in 1956 while living in New York City. She originally conceived it as a novel focusing on main character Jean Louise “Scout” Finch as an adult returning to Maycomb for a summer visit and confronting the racial realities of her hometown in response to the civil rights movement; it was to be titled Go Set a Watchman. Her editor at Lippincott Publishers, Tay Hohoff, convinced her to pull out the flashbacks of Scout’s youth and refocus the novel around them. Lee did so, and the result, To Kill A Mockingbird, was published in 1960 to critical acclaim and public enthusiasm, winning the 1961 Pulitzer Prize for fiction.

To Kill A Mockingbird

The story told in the novel parallels two court cases that took place in Alabama but was not based directly on them: The Scottsboro Trials of 1931, in which nine black youths were tried for allegedly raping two white women on a train in north Alabama; and a November 1933 incident in Monroeville in which Naomi Lowery, a poor white woman, alleged that Walter Lett, a black ex-convict, sexually assaulted her. Lee began work on what would become the novel in 1956 while living in New York City. She originally conceived it as a novel focusing on main character Jean Louise “Scout” Finch as an adult returning to Maycomb for a summer visit and confronting the racial realities of her hometown in response to the civil rights movement; it was to be titled Go Set a Watchman. Her editor at Lippincott Publishers, Tay Hohoff, convinced her to pull out the flashbacks of Scout’s youth and refocus the novel around them. Lee did so, and the result, To Kill A Mockingbird, was published in 1960 to critical acclaim and public enthusiasm, winning the 1961 Pulitzer Prize for fiction.

The novel is set in the fictional town of Maycomb, Alabama, (loosely based on Lee’s hometown of Monroeville, Monroe County) between the summer of 1932 and Halloween night of 1935, during the Great Depression when many blacks and whites shared a common poverty. The plot is simple: three young children—Jean Louise “Scout” Finch, her older brother, Jem, and their friend, Dill—spend their summer holidays trying to learn more about their reclusive neighbor Arthur “Boo” Radley and soon become caught up in the unfolding drama of the trial of Tom Robinson, a black man accused of raping Mayella Ewell, the daughter of a poor white man, Robert E. Lee “Bob” Ewell. Jean Louise narrates the story from adulthood as a reminiscence of her childhood. She is six when the novel begins and nine when it ends. Essentially a coming-of-age novel about lost innocence, Scout learns that her otherwise decent and fair-minded white neighbors ignore the evidence when judging a black man accused of a violent crime. She also discovers that the black members of her town are complex people, some ignorant and evil and others wise and good. She learns the same lessons about the middle-class white residents of Maycomb and about the poor but proud Cunningham family and the poor but not-very-proud Ewells. The hero of the story is Scout’s lawyer father, Atticus Finch, who agrees to defend Tom Robinson. The case is hopeless from the beginning despite Finch’s best efforts, and it exposes him and his family to the anger and ostracism of Maycomb’s white people, violent retribution by Bob Ewell, and the admiration of the town’s black population.

Old Monroe County Courthouse

In 1962, Universal Pictures released a film adaptation featuring Gregory Peck in the starring role, Robert Duvall as Boo Radley, and Birmingham natives Mary Badham as Scout and Philip Alford as Jem. Renowned playwright Horton Foote wrote the screenplay, and Elmer Bernstein composed the memorable musical score. In 1963, the film was nominated for eight Academy Awards and won three: Gregory Peck for best actor; Horton Foote for best screenplay; and Henry Bumstead for best art direction. British playwright Christopher Sergel adapted the book into a play that is widely produced, including an annual spring performance at the Monroe County courthouse in Monroeville and periodic performances at the Alabama Shakespeare Festival in Montgomery.

Old Monroe County Courthouse

In 1962, Universal Pictures released a film adaptation featuring Gregory Peck in the starring role, Robert Duvall as Boo Radley, and Birmingham natives Mary Badham as Scout and Philip Alford as Jem. Renowned playwright Horton Foote wrote the screenplay, and Elmer Bernstein composed the memorable musical score. In 1963, the film was nominated for eight Academy Awards and won three: Gregory Peck for best actor; Horton Foote for best screenplay; and Henry Bumstead for best art direction. British playwright Christopher Sergel adapted the book into a play that is widely produced, including an annual spring performance at the Monroe County courthouse in Monroeville and periodic performances at the Alabama Shakespeare Festival in Montgomery.

The novel’s popular acclaim has increased with the passing decades. Pollsters estimated that three out of four high school students were required to read it. In 1991, the Library of Congress asked 5,000 patrons to name the book that had made the biggest difference in their lives. To Kill a Mockingbird came in second, after the Bible. In 1999, American librarians voted the book the best novel of the twentieth century. TV Guide and the American Film Institute have rated the movie consistently among the top 50 films of all time, and Atticus Finch is regularly cited as one of the greatest heroes in film. According to the Library of Congress, the novel is the country’s most popular selection for citywide reading programs, in which residents of a community read a common novel over the course of a year. Perhaps even more astounding, the novel is required reading in many schools in Ireland, Great Britain, Australia, and Canada, as well as in many non-English-speaking countries. The novel has been translated into more than forty languages.

The Modern Library’s list of the 100 greatest English-language novels of the twentieth century (as decided by a small committee of writers) omitted the novel, however. Some critics consider Atticus Finch an imperfect hero. The casual familiarity between the Finches and their black servant, Calpurnia, strikes some as condescending and paternalistic. Critics add that the book breaks no new literary ground, as compared with the novels of other writers, such as those by Mississippi native William Faulkner.

Nelle Harper Lee

Defenders praise Lee precisely for the simplicity of her style, her almost mystical evocation of childhood, and her sensitive portrayal of children as they slip the bounds of innocence and discover the darkness of adulthood. As for racial paternalism, defenders note that the novel was written in the late 1950s to describe the racially segregated world of the 1930s and consider it unreasonable to impose late-twentieth-century, post-civil-rights-era ideas about race upon it. For the novel’s fans, Atticus is a remarkable figure in American literature not because he transcends the segregationist mores of Maycomb but because he demands justice and tolerance within the framework of his own time. Popular acclaim for the novel owes much to the message of tolerance that Lee proclaimed during an intolerant age. Atticus’s admonition to his children that they will never understand a person until they consider life from his or her point of view is viewed as trite by some critics, but the novel’s message had profound effects many oppressed people throughout the world.

Nelle Harper Lee

Defenders praise Lee precisely for the simplicity of her style, her almost mystical evocation of childhood, and her sensitive portrayal of children as they slip the bounds of innocence and discover the darkness of adulthood. As for racial paternalism, defenders note that the novel was written in the late 1950s to describe the racially segregated world of the 1930s and consider it unreasonable to impose late-twentieth-century, post-civil-rights-era ideas about race upon it. For the novel’s fans, Atticus is a remarkable figure in American literature not because he transcends the segregationist mores of Maycomb but because he demands justice and tolerance within the framework of his own time. Popular acclaim for the novel owes much to the message of tolerance that Lee proclaimed during an intolerant age. Atticus’s admonition to his children that they will never understand a person until they consider life from his or her point of view is viewed as trite by some critics, but the novel’s message had profound effects many oppressed people throughout the world.

To Kill A Mockingbird has played a significant role in the intense half-century debate Americans have had about the role of education in fostering moral values. Should public schools teach values? If so, what values? Whose values? Hundreds of thousands of American teachers have chosen to teach To Kill A Mockingbird, deciding that Harper Lee’s values represent the best of humanity: tolerance; kindness; civility; justice; the courage to face down community or family

To Kill A Mockingbird Play in Monroeville

when they are wrong; and the compassion to love them despite their flaws. Despite these qualities, the novel is one of the books most frequently banned by local school boards because of the plot (which involves an alleged rape) and the theme (tolerance for people who do not conform to community norms). When the book first appeared, Alabama’s White Citizens Council called the work “communistic” for promoting racial integration and tried to have the state director of the Alabama Public Library Service fired for refusing to remove it from state libraries.

To Kill A Mockingbird Play in Monroeville

when they are wrong; and the compassion to love them despite their flaws. Despite these qualities, the novel is one of the books most frequently banned by local school boards because of the plot (which involves an alleged rape) and the theme (tolerance for people who do not conform to community norms). When the book first appeared, Alabama’s White Citizens Council called the work “communistic” for promoting racial integration and tried to have the state director of the Alabama Public Library Service fired for refusing to remove it from state libraries.

Ironically, a novel written by a woman from Monroeville in Alabama’s Black Belt has become the primary literary instrument worldwide for teaching values of racial justice, tolerance for people different from ourselves, and the need for moral courage in the face of community prejudice and ostracism.

Additional Resources

Flynt, Wayne. “Class and Race, Text and Context in To Kill A Mockingbird.” In The Many Souths: Class in Southern Culture, edited by Waldemar Zacharesiewicz. Tübingen, Germany: Stauffenburg Verlag, 2003.

Johnson, Claudia Durst. Understanding To Kill A Mockingbird: A Student Casebook to Issues, Sources, and Historic Documents. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1994.

Mahoney, John, and Stewart Martin. To Kill A Mockingbird by Harper Lee. Letts Study Aids Series. London: Charles Letts and Co., 1987.

Petry, Alice Hall, ed. On Harper Lee: Essays and Reflections. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2007.

Shields, Charles J. Mockingbird: A Portrait of Harper Lee. New York: Henry Holt, 2006.