Hank Williams Sr.

Hank Willliams Sr.

Few performers in the history of country music can compare with Hank Williams Sr. (1923-1953) in terms of importance and influence. A key figure in the development of modern country music, Williams personified the musical genre’s shift from a regional, rural phenomenon to nationwide, urban acceptance in the late 1940s. Revered by fans drawn to the sincerity of his songs and his singing and glorified by an industry that once ostracized him, Hank Williams, during his brief 29 years, was instrumental in turning “hillbilly” music into “country” music.

Hank Willliams Sr.

Few performers in the history of country music can compare with Hank Williams Sr. (1923-1953) in terms of importance and influence. A key figure in the development of modern country music, Williams personified the musical genre’s shift from a regional, rural phenomenon to nationwide, urban acceptance in the late 1940s. Revered by fans drawn to the sincerity of his songs and his singing and glorified by an industry that once ostracized him, Hank Williams, during his brief 29 years, was instrumental in turning “hillbilly” music into “country” music.

Hiram “Hank” Williams was born on September 17, 1923, near Mount Olive in Butler County, Alabama, to Lon Williams, a locomotive engineer, and Lillie Williams, a church organist. The couple separated early in Hank’s life, and he was raised primarily by his mother during his formative years. Williams spent most of his childhood in Georgiana and Greenville, both in Butler County, and early on became enthralled with music, playing harmonica, learning the organ from his mother, and acquiring his first guitar around the time he was eight years old.

Williams Family Reunion

Like many other young boys growing up in the South at the time, Williams was a fan of singer Jimmie Rodgers, a Mississippian whose groundbreaking music blended blues guitar, evocative yodeling, and vivid lyrical imagery. Williams’ sound was further influenced by his friendship with African American street singer Rufus “Tee Tot” Payne, who helped Williams hone his guitar-playing skills and, more importantly, develop the blues phrasing and blues rhythms that he would later use in his own singing style.

Williams Family Reunion

Like many other young boys growing up in the South at the time, Williams was a fan of singer Jimmie Rodgers, a Mississippian whose groundbreaking music blended blues guitar, evocative yodeling, and vivid lyrical imagery. Williams’ sound was further influenced by his friendship with African American street singer Rufus “Tee Tot” Payne, who helped Williams hone his guitar-playing skills and, more importantly, develop the blues phrasing and blues rhythms that he would later use in his own singing style.

In 1937, Lillie Williams and her son moved to the capital city of Montgomery, where Lillie opened a boarding house. Hank augmented the family income by shining shoes and selling peanuts on the street. He maintained his interest in music and eventually began

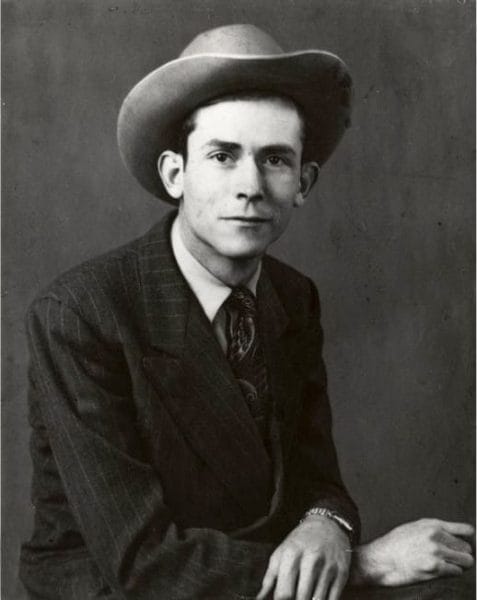

Hank and Hezzy’s Driftin’ Cowboys

performing on Montgomery’s WSFA radio station, where he remained on the air intermittently from 1937 to 1942. The young performer eventually formed a band called the Driftin’ Cowboys and began playing in the area. Singing without amplification, and above the sounds of a band, Williams developed a full-throated style similar to that of Grand Ole Opry star Roy Acuff. As one of Alabama’s 540,000 urbanites in 1940 (representing 29 percent of the state’s population), and one of only about 250,000 who lived in the state’s large cities, the Williams family represented Alabama’s demographic future. World War II ultimately provided the impetus for the state’s rapid urbanization of the 1940s. By 1950, more than 40 percent of the state’s population resided in urban areas, nearly half of them in larger metropolitan cities. A combination of the Great Depression in the 1930s and economic opportunities during the 1940s spurred these developments, and Williams found himself right in the middle of them at the advent of World War II. Turned down for military service because of back problems, Williams worked war-related jobs in Portland, Oregon, and Mobile, Mobile County.

Hank and Hezzy’s Driftin’ Cowboys

performing on Montgomery’s WSFA radio station, where he remained on the air intermittently from 1937 to 1942. The young performer eventually formed a band called the Driftin’ Cowboys and began playing in the area. Singing without amplification, and above the sounds of a band, Williams developed a full-throated style similar to that of Grand Ole Opry star Roy Acuff. As one of Alabama’s 540,000 urbanites in 1940 (representing 29 percent of the state’s population), and one of only about 250,000 who lived in the state’s large cities, the Williams family represented Alabama’s demographic future. World War II ultimately provided the impetus for the state’s rapid urbanization of the 1940s. By 1950, more than 40 percent of the state’s population resided in urban areas, nearly half of them in larger metropolitan cities. A combination of the Great Depression in the 1930s and economic opportunities during the 1940s spurred these developments, and Williams found himself right in the middle of them at the advent of World War II. Turned down for military service because of back problems, Williams worked war-related jobs in Portland, Oregon, and Mobile, Mobile County.

Williams returned to Montgomery near the conclusion of the war, formed a band, and resumed his pursuit of a musical career in earnest. In addition to performing at dances and other local events, Williams and his group also played the “honky tonks,” the often rough and rowdy beer joints frequented by the city’s newcomers. The experience helped to form Williams’s percussive, rhythmic musical style, ultimately a combination of Payne’s teaching and the influence of one of honky-tonk music’s pioneers, Ernest Tubb.

Hank Williams Sr. in Luverne

Having amassed a loyal following in Alabama, Williams set his sights on a recording contract, which he acquired in 1946 with the assistance of talent scout and song publisher Fred Rose. The singer made his first recordings for Sterling (based in New York) in December and, on the strength of his regionally popular song “Honky Tonkin” secured a recording contract with a larger record label, MGM, in the spring of 1947. One of Williams’s earliest hits, “Move It On Over,” earned him a chance to play on the Louisiana Hayride radio program in Shreveport in 1948, where he soon became a regular member of the cast. This proved to be his breakthrough, as the station’s powerful 50,000-watt signal reached not only the entire South, but much of the nation as well. Not long after joining the program, Williams recorded “Lovesick Blues,” a song written by Clifford Friend and Irving Mills. The record became a national hit, topping Billboard magazine’s country chart for 16 weeks. “Lovesick Blues” and its follow-up, “Wedding Bells,” landed Williams an appearance on country music’s premier radio show, the Grand Ole Opry, in June 1949.

Hank Williams Sr. in Luverne

Having amassed a loyal following in Alabama, Williams set his sights on a recording contract, which he acquired in 1946 with the assistance of talent scout and song publisher Fred Rose. The singer made his first recordings for Sterling (based in New York) in December and, on the strength of his regionally popular song “Honky Tonkin” secured a recording contract with a larger record label, MGM, in the spring of 1947. One of Williams’s earliest hits, “Move It On Over,” earned him a chance to play on the Louisiana Hayride radio program in Shreveport in 1948, where he soon became a regular member of the cast. This proved to be his breakthrough, as the station’s powerful 50,000-watt signal reached not only the entire South, but much of the nation as well. Not long after joining the program, Williams recorded “Lovesick Blues,” a song written by Clifford Friend and Irving Mills. The record became a national hit, topping Billboard magazine’s country chart for 16 weeks. “Lovesick Blues” and its follow-up, “Wedding Bells,” landed Williams an appearance on country music’s premier radio show, the Grand Ole Opry, in June 1949.

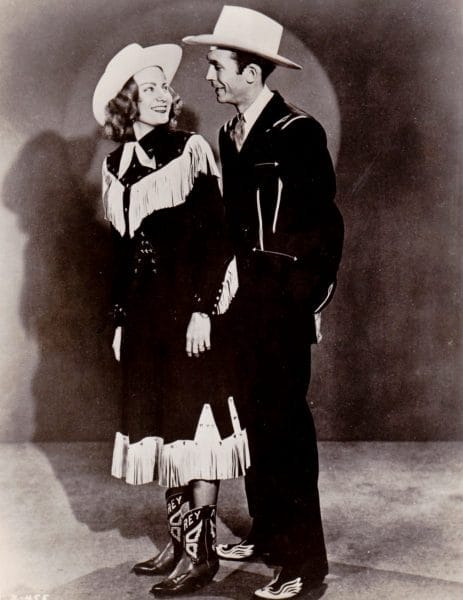

Hank and Audrey Williams

Despite all the success of his musical career, Williams’s personal life was extremely turbulent, stemming primarily from alcohol abuse, a problem that intensified his stormy relationship with Audrey Sheppard, of Banks in Pike County, Alabama, whom he married in 1944. In 1949, their son Hank Jr. was born. The couple initially worked as a team to promote Hank’s career, but a combination of his substance abuse and mutual incompatibility led them to separate briefly in 1948 and later divorce. The couple’s volatile relationship made its way into many of Williams’s most famous songs, ironically contributing to the success that the couple had pursued with such vigor together early in their marriage. Hank Williams’s songs most often featured themes of heartbreak, heartache, and the dissolution of relationships. Some of these songs, including “The Blues Come Around,” “You’re Gonna Change, or I’m Gonna Leave,” and “Why Don’t You Love Me,” were set to up-tempo rhythms that belied the despair and anger behind the lyrics. Mid- and slow-tempo numbers such as “I Don’t Care If Tomorrow Never Comes,” “Long Gone Lonesome Blues,” and “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry” offer unparalleled images of loneliness and longing, with heartfelt singing that adds considerable weight to powerful lyrics.

Hank and Audrey Williams

Despite all the success of his musical career, Williams’s personal life was extremely turbulent, stemming primarily from alcohol abuse, a problem that intensified his stormy relationship with Audrey Sheppard, of Banks in Pike County, Alabama, whom he married in 1944. In 1949, their son Hank Jr. was born. The couple initially worked as a team to promote Hank’s career, but a combination of his substance abuse and mutual incompatibility led them to separate briefly in 1948 and later divorce. The couple’s volatile relationship made its way into many of Williams’s most famous songs, ironically contributing to the success that the couple had pursued with such vigor together early in their marriage. Hank Williams’s songs most often featured themes of heartbreak, heartache, and the dissolution of relationships. Some of these songs, including “The Blues Come Around,” “You’re Gonna Change, or I’m Gonna Leave,” and “Why Don’t You Love Me,” were set to up-tempo rhythms that belied the despair and anger behind the lyrics. Mid- and slow-tempo numbers such as “I Don’t Care If Tomorrow Never Comes,” “Long Gone Lonesome Blues,” and “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry” offer unparalleled images of loneliness and longing, with heartfelt singing that adds considerable weight to powerful lyrics.

Hank Williams Sr. and Jr.

Williams’s appeal to his audience lay primarily in the sincerity of his performances and the strength of his writing. Combining Jimmie Rodgers’s penchant for pastoralism with his own remarkable ability to explore the depths of human emotions using simple language, Williams could convey both a lust for life (“Settin’ the Woods on Fire,” “Baby, We’re Really in Love”) and a sense of utter despair (“Cold, Cold Heart,” “May You Never Be Alone”) with equal conviction. The sincerity of Williams’s performances appealed to his listeners, many of whom were also new to city life and shared Williams’s feelings of displacement and disillusionment. To the thousands of southerners displaced by migration both within the region and in other parts of the United States, Williams offered a sense of commonality and familiarity.

Hank Williams Sr. and Jr.

Williams’s appeal to his audience lay primarily in the sincerity of his performances and the strength of his writing. Combining Jimmie Rodgers’s penchant for pastoralism with his own remarkable ability to explore the depths of human emotions using simple language, Williams could convey both a lust for life (“Settin’ the Woods on Fire,” “Baby, We’re Really in Love”) and a sense of utter despair (“Cold, Cold Heart,” “May You Never Be Alone”) with equal conviction. The sincerity of Williams’s performances appealed to his listeners, many of whom were also new to city life and shared Williams’s feelings of displacement and disillusionment. To the thousands of southerners displaced by migration both within the region and in other parts of the United States, Williams offered a sense of commonality and familiarity.

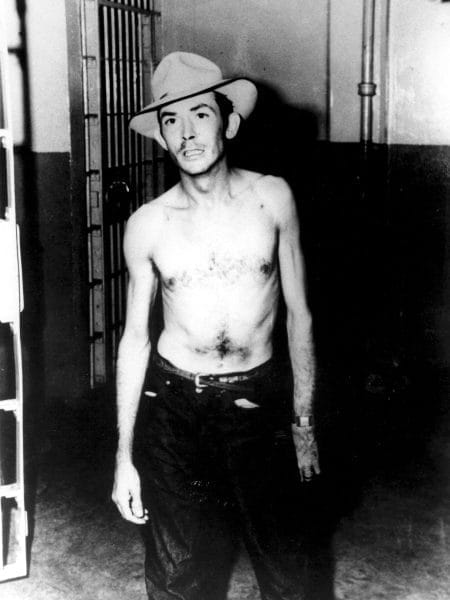

Hank Williams in Jail

By the end of 1951, Williams had amassed 24 top 10 singles, with six reaching number one. In addition to success on the country charts, he also became a favored song source for such pop singers as Frankie Laine, Jo Stafford, Guy Mitchell, and, most notably, Tony Bennett, whose recording of “Cold, Cold Heart” reached number one on the pop charts in 1951. Despite all the success, Williams’s personal and professional lives were in peril by the middle of 1952. Divorced from Audrey in July and fired from the Opry in August for chronic absenteeism, Williams headed back to Alabama to regroup, and the Louisiana Hayride eventually rehired him in late summer. Prior to his departure, however, he had a brief affair with secretary Bobbie Jett, and the couple lived together during the summer of 1952 in a cabin on Lake Martin. In 1953, Jett gave birth to a daughter, Antha Belle Jett, in Montgomery soon after his death.

Hank Williams in Jail

By the end of 1951, Williams had amassed 24 top 10 singles, with six reaching number one. In addition to success on the country charts, he also became a favored song source for such pop singers as Frankie Laine, Jo Stafford, Guy Mitchell, and, most notably, Tony Bennett, whose recording of “Cold, Cold Heart” reached number one on the pop charts in 1951. Despite all the success, Williams’s personal and professional lives were in peril by the middle of 1952. Divorced from Audrey in July and fired from the Opry in August for chronic absenteeism, Williams headed back to Alabama to regroup, and the Louisiana Hayride eventually rehired him in late summer. Prior to his departure, however, he had a brief affair with secretary Bobbie Jett, and the couple lived together during the summer of 1952 in a cabin on Lake Martin. In 1953, Jett gave birth to a daughter, Antha Belle Jett, in Montgomery soon after his death.

In the autumn of 1952, Williams married Billie Jean Jones of Louisiana and had two singles (“Jambalaya” and “Settin’ the Woods on Fire”) rising on the charts. His life and career suddenly appeared to be on the upswing. Unfortunately, Williams’s health steadily declined in November and December. Back problems that had plagued him his entire life grew worse and caused him to increase his drinking, which in turn exacerbated developing heart problems. In search of relief from the painful ailments that plagued him, Williams began taking pain medication as well. After a brief tour in Texas, Williams returned to Montgomery in late December to rest before heading north for a scheduled New Year’s Day appearance in Canton, Ohio. During the trip northward, Williams slipped into unconsciousness and was pronounced dead on New Year’s Day in Oak Hill, West Virginia, at the age of 29. Williams was interred in Montgomery’s Oakwood Annex Cemetery, and his grave attracts many visitors each year.

Hank Williams Boyhood Home and Museum

Following his death, sales of Williams’s records skyrocketed. An estimated 20,000 people attended his funeral, held in Montgomery’s Municipal Auditorium on January 4, 1953, with country star Red Foley singing “(There’ll Be) Peace in the Valley” and Roy Acuff and others performing “I Saw the Light.” Williams’s unofficial coronation as country music’s most legendary performer occurred in September 1953, when Montgomery celebrated Hank Williams Day. Two days of honors and accolades culminated in a show at Cramton Bowl, where 8,500 fans showed up to see and hear a musical tribute to one of Alabama’s greatest contributions to country music.

Hank Williams Boyhood Home and Museum

Following his death, sales of Williams’s records skyrocketed. An estimated 20,000 people attended his funeral, held in Montgomery’s Municipal Auditorium on January 4, 1953, with country star Red Foley singing “(There’ll Be) Peace in the Valley” and Roy Acuff and others performing “I Saw the Light.” Williams’s unofficial coronation as country music’s most legendary performer occurred in September 1953, when Montgomery celebrated Hank Williams Day. Two days of honors and accolades culminated in a show at Cramton Bowl, where 8,500 fans showed up to see and hear a musical tribute to one of Alabama’s greatest contributions to country music.

Hank Williams’s Cadillac

The legacy of Hank Williams remains alive today, with the heartfelt nature of his performances and the vivid imagery and honesty of his lyrics remaining the benchmark by which country music performers are measured. In a recording career that spanned only six years, Williams wrote several classics of American music, including “Your Cheatin’ Heart,” “Hey Good Lookin’,” and “I Saw the Light,” and together with Ernest Tubb, Floyd Tillman, and Lefty Frizzell forged the honky-tonk sound that became the standard for country music in the latter half of the twentieth century. More than 50 years after his death, Hank Williams remains enshrined in the hearts and minds of his fans and music followers as a folk hero and country music icon. In April 2010, the Pulitzer Prize Board awarded Williams with a posthumous Special Citation lifetime achievement award to honor his contributions to music. His life and career are celebrated at two museums in Alabama: the Hank Williams Museum in Montgomery and the Hank Williams Boyhood Home and Museum in Georgiana.

Hank Williams’s Cadillac

The legacy of Hank Williams remains alive today, with the heartfelt nature of his performances and the vivid imagery and honesty of his lyrics remaining the benchmark by which country music performers are measured. In a recording career that spanned only six years, Williams wrote several classics of American music, including “Your Cheatin’ Heart,” “Hey Good Lookin’,” and “I Saw the Light,” and together with Ernest Tubb, Floyd Tillman, and Lefty Frizzell forged the honky-tonk sound that became the standard for country music in the latter half of the twentieth century. More than 50 years after his death, Hank Williams remains enshrined in the hearts and minds of his fans and music followers as a folk hero and country music icon. In April 2010, the Pulitzer Prize Board awarded Williams with a posthumous Special Citation lifetime achievement award to honor his contributions to music. His life and career are celebrated at two museums in Alabama: the Hank Williams Museum in Montgomery and the Hank Williams Boyhood Home and Museum in Georgiana.

Hank Williams Jr. went on to pursue a very successful country music career, as did his son, Hank Williams III. Antha Belle Jett would later change her name to Jett Williams and also make a career as a country singer. She fought a protracted legal battle to prove her paternity and gain a share of the Williams estate, winning the case officially in 1990.

Recordings

Hank Williams: The Original Singles Collection . . . Plus. Produced by Colin Escott. New York: Polygram Records, 1990.

Hank Williams—40 Greatest Hits. New York: Polygram Records, 1990.

The Complete Hank Williams. Nashville, Tenn.: Mercury Nashville, 1998.

Further Reading

- Escott, Colin, et. al. Hank Williams: The Biography. Boston: Little, Brown, 1994.

- Hemphill, Paul. Lovesick Blues: The Life of Hank Williams. New York: Viking, 2005.

- Whitburn, Joel. The Billboard Book of Top 40 Country Hits. New York: Billboard Books, 1996.

- Williams, Roger M. Hank Williams. Alexandria, Va.: Time-Life Records, 1981.