Helen Keller

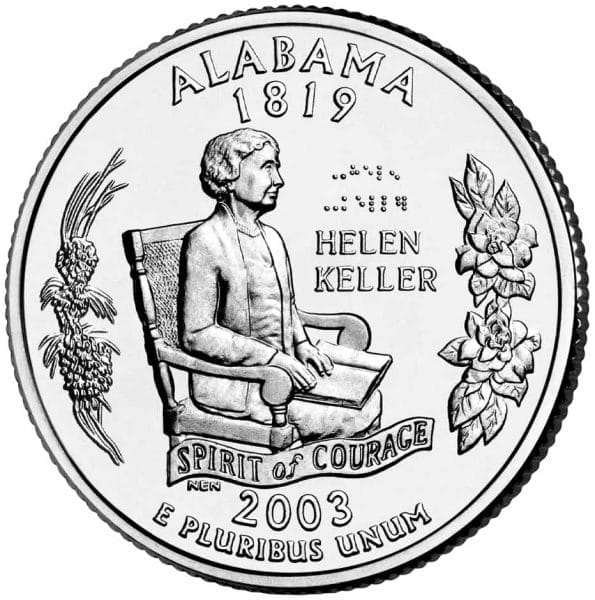

Alabama State Quarter

Few Alabamians have risen to the level of worldwide fame held by Helen Keller (1880-1968). Ironically, despite her many accomplishments as an adult, she is probably best remembered today as the deaf and blind child who learned sign language from her teacher Anne Sullivan at her parents’ backyard water pump. During her lifetime, she was known for her tireless activism on behalf of workers’ and women’s rights, her literary work, and her tenure as an unofficial U.S. ambassador to the world. Although Keller left Alabama at the age of eight, she always claimed Ivy Green, her family’s house in Tuscumbia, as home, and she continued to identify herself as a southerner throughout her life and travels. She was selected to represent Alabama on its 2003 state quarter, and on October 7, 2009, a bronze statue depicting seven-year-old Keller at the water pump replaced that of J. L. M. Curry in Statuary Hall in the U.S. Capitol.

Alabama State Quarter

Few Alabamians have risen to the level of worldwide fame held by Helen Keller (1880-1968). Ironically, despite her many accomplishments as an adult, she is probably best remembered today as the deaf and blind child who learned sign language from her teacher Anne Sullivan at her parents’ backyard water pump. During her lifetime, she was known for her tireless activism on behalf of workers’ and women’s rights, her literary work, and her tenure as an unofficial U.S. ambassador to the world. Although Keller left Alabama at the age of eight, she always claimed Ivy Green, her family’s house in Tuscumbia, as home, and she continued to identify herself as a southerner throughout her life and travels. She was selected to represent Alabama on its 2003 state quarter, and on October 7, 2009, a bronze statue depicting seven-year-old Keller at the water pump replaced that of J. L. M. Curry in Statuary Hall in the U.S. Capitol.

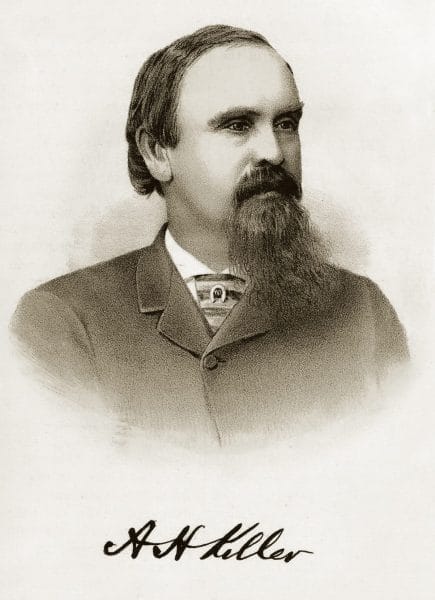

Arthur Keller

Helen Keller was born on June 27, 1880, in Tuscumbia, Colbert County, to Capt. Arthur H. Keller, a newspaper editor, and Kate Adams Keller, and had a brother and a sister. At the age of 19 months, Keller contracted what doctors at the time called “brain fever,” which may have been scarlet fever. Although Keller survived the illness, it left her deaf and blind. As she grew, her parents became more and more frustrated with their increasingly uncontrollable daughter. Family members urged the Kellers to place Helen in an asylum or institution. Apparently neither parent considered sending her to the Alabama School for the Deaf and Blind in Talladega, perhaps because southerners often looked at such educational institutions with suspicion given the connections between educational reformers and abolitionism.

Arthur Keller

Helen Keller was born on June 27, 1880, in Tuscumbia, Colbert County, to Capt. Arthur H. Keller, a newspaper editor, and Kate Adams Keller, and had a brother and a sister. At the age of 19 months, Keller contracted what doctors at the time called “brain fever,” which may have been scarlet fever. Although Keller survived the illness, it left her deaf and blind. As she grew, her parents became more and more frustrated with their increasingly uncontrollable daughter. Family members urged the Kellers to place Helen in an asylum or institution. Apparently neither parent considered sending her to the Alabama School for the Deaf and Blind in Talladega, perhaps because southerners often looked at such educational institutions with suspicion given the connections between educational reformers and abolitionism.

Many financially secure families did send deaf or blind children to highly reputed schools in the Northeast. Through contacts with inventor and deaf educator Alexander Graham Bell, Keller’s parents contacted Michael Anagnos, director of Boston’s Perkins School for the Blind in 1886. He responded by sending his star student and recent graduate, the financially needy and orphaned Anne Sullivan, to work with the seven-year-old Helen Keller. Sullivan was quite familiar with living with a disability, having lost her sight after a childhood illness. Despite surgeries at Perkins that restored some function, Sullivan’s eyesight remained erratic and limited for most of her life, and her eyes frequently caused her great pain.

Helen Keller Birthplace

In March 1887, the 21-year-old Sullivan arrived at Ivy Green and started what would be a lifelong partnership with Helen Keller. The two generally communicated by finger-spelling, a process by which individual letters are spelled out in sign language on the open palm. Soon after she was able to teach the young Keller language, the forceful Sullivan persuaded her reluctant parents to allow the pair to move to Boston so that Keller could attend the Perkins School for the Blind. She argued that Helen needed to be removed from her overly protective family circle and that Perkins was the sensible educational choice.

Helen Keller Birthplace

In March 1887, the 21-year-old Sullivan arrived at Ivy Green and started what would be a lifelong partnership with Helen Keller. The two generally communicated by finger-spelling, a process by which individual letters are spelled out in sign language on the open palm. Soon after she was able to teach the young Keller language, the forceful Sullivan persuaded her reluctant parents to allow the pair to move to Boston so that Keller could attend the Perkins School for the Blind. She argued that Helen needed to be removed from her overly protective family circle and that Perkins was the sensible educational choice.

Keller later wrote of her growing desire for education in her book Teacher (1955), a tribute to Sullivan. After completing her education at Perkins, she and Sullivan spent several years in New York attempting to develop her lip-reading and speaking skills at the Wright-Humason School for the Deaf. Then, despite the opposition of many financial supporters, she sought admission to Radcliffe College, the women’s institution associated with Harvard University. After several more years of preparation at the Cambridge School for Young Ladies, Keller entered the prestigious institution in the fall of 1900 and graduated in 1904.

Helen Keller and Anne Sullivan

While in college, Keller undertook an essay assignment that evolved into a magazine serial and then into her 1903 autobiography, The Story of My Life, which remains her most famous publication. In it, she chronicled her education and first 23 years, and Sullivan provided supplementary accounts of the teaching process. Harvard scholar and friend John Macy helped negotiate a publishing contract and edited the book, and he married Sullivan in 1905. Literary success revolutionized Keller’s world. The autobiography became an almost unparalleled best seller in multiple languages and caused Keller to dream of life as an economically self-sufficient author.

Helen Keller and Anne Sullivan

While in college, Keller undertook an essay assignment that evolved into a magazine serial and then into her 1903 autobiography, The Story of My Life, which remains her most famous publication. In it, she chronicled her education and first 23 years, and Sullivan provided supplementary accounts of the teaching process. Harvard scholar and friend John Macy helped negotiate a publishing contract and edited the book, and he married Sullivan in 1905. Literary success revolutionized Keller’s world. The autobiography became an almost unparalleled best seller in multiple languages and caused Keller to dream of life as an economically self-sufficient author.

In The Story of My Life (1903), it is clear that Keller’s Alabama and southern ties formed and constituted a vital element of her public identity. She characterized Ivy Green and its garden as “the paradise of my childhood,” and detailed the smells, location, and sometimes texture of each flower and vine. She claimed her regional roots fondly but grappled with them at times. Throughout her lifetime, she increasingly questioned and then challenged segregation, racially based economic inequalities, and racial violence.

Ivy Green Water Pump

After graduating college, Keller assumed that she would build on the massive literary success of her autobiograpnhy, but she found supporting herself as an author more difficult than she anticipated. Editors and the reading public only wanted to read about her disability, but Keller wanted to write on her expanding and increasingly controversial economic, political, and international views. The critics panned and few bought The World I Live In (1908), Song of the Stone Wall (1910), and her collection of political essays Out of the Dark (1913). She and Sullivan tried the lecture circuit, starred in the 1919 Hollywood film Deliverance (which also featured her brother), and lectured about her education and politics on the vaudeville stage in an effort to support themselves. Neither woman enjoyed the constant travel and public scrutiny, and Sullivan (who both married and separated from her husband John Macy during this time period) particularly disliked the stress of travel and public performance.

Ivy Green Water Pump

After graduating college, Keller assumed that she would build on the massive literary success of her autobiograpnhy, but she found supporting herself as an author more difficult than she anticipated. Editors and the reading public only wanted to read about her disability, but Keller wanted to write on her expanding and increasingly controversial economic, political, and international views. The critics panned and few bought The World I Live In (1908), Song of the Stone Wall (1910), and her collection of political essays Out of the Dark (1913). She and Sullivan tried the lecture circuit, starred in the 1919 Hollywood film Deliverance (which also featured her brother), and lectured about her education and politics on the vaudeville stage in an effort to support themselves. Neither woman enjoyed the constant travel and public scrutiny, and Sullivan (who both married and separated from her husband John Macy during this time period) particularly disliked the stress of travel and public performance.

In the decades after college, Keller also become increasingly involved in politics. She joined the Socialist Party of America in 1909 and became an advocate of suffrage, unemployment benefits, and legalized birth control for women and a defender of the radical Industrial Workers of the World union. She criticized World War I as a profit-making venture for industrialists and urged working-class men to resist the war. She supported striking workers and jailed dissidents and expressed passionate views about the need for a just and economically equitable society. She blamed industrialization and poverty for causing disability among a disproportionately large number of working-class people and became increasingly concerned about racial inequalities. She expressed all of these sentiments through public speeches, newspaper and magazine articles, interviews, and appearances at rallies.

Though she was a discerning woman of political opinions and activism, Keller frequently encountered people who believed that her disability disqualified her from civic life. Detractors sometimes voiced these criticisms in regional terms. For example, when she voiced political opinions considered radical in the early twentieth century, opponents from Alabama attributed her views to the “Yankee” influence of Anne Sullivan Macy and her then-husband John Macy. When a letter and donation Keller sent to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People became public knowledge in 1916, an Alabama newspaper wrote that it reflected lingering abolitionist sentiment. According to her critics, her disability left her politically pliable, especially by what they considered immoral and irrational northerners, and incapable of intentional deliberation. Such attitudes frustrated and enraged her.

Helen Keller and Pres. Calvin Coolidge

Keller entered the 1920s seeking a meaningful public life and financial stability. The newly created American Foundation for the Blind (AFB) supplied both, becoming the center of her and Anne Macy’s lives as they worked from their Forest Hills, New York, home. Working on behalf of blind people with and through the AFB, Keller became an inveterate fundraiser and political lobbyist. From the 1920s through the early 1940s, she worked almost ceaselessly, raising funds and lobbying state and national legislatures. She emphasized educational and employment possibilities for people with disabilities, particularly those who were blind. Amidst these efforts she also published My Religion (1927). In 1896, she had converted to Swedenborgianism, a Christian sect established by eighteenth-century Swedish spiritual leader Emanuel Swedenborg and a growing movement among turn-of-the-century Americans. Keller valued the opportunity to share that faith in My Religion. In 1929, she published Midstream, a continuation of her 1903 autobiography.

Helen Keller and Pres. Calvin Coolidge

Keller entered the 1920s seeking a meaningful public life and financial stability. The newly created American Foundation for the Blind (AFB) supplied both, becoming the center of her and Anne Macy’s lives as they worked from their Forest Hills, New York, home. Working on behalf of blind people with and through the AFB, Keller became an inveterate fundraiser and political lobbyist. From the 1920s through the early 1940s, she worked almost ceaselessly, raising funds and lobbying state and national legislatures. She emphasized educational and employment possibilities for people with disabilities, particularly those who were blind. Amidst these efforts she also published My Religion (1927). In 1896, she had converted to Swedenborgianism, a Christian sect established by eighteenth-century Swedish spiritual leader Emanuel Swedenborg and a growing movement among turn-of-the-century Americans. Keller valued the opportunity to share that faith in My Religion. In 1929, she published Midstream, a continuation of her 1903 autobiography.

In 1936, Anne Sullivan Macy died at their home in Forest Hills, New York, at the age of 70, profoundly shaking Keller and forcing her to expand both her personal and professional worlds. During Macy’s last months, the two women had received a visit from Takeo Iwahashi, an English-speaking Christian director of a school for the blind in Osaka, Japan, and the Japanese translator of The Story of My Life. He urged Keller to visit Japan, and Macy exacted a promise that Keller would someday follow through. In 1937, after Macy’s death, Keller made good on her promise. Desperately in need of escape from her grief, the 56-year-old Keller, unsure of the rest of her life, saw in the trip the possibility of a new focus.

Helen Keller in Japan

A subsequent trip to Japan in 1948 was the catalyst for Keller’s transformation from tourist to semi-official ambassador for the United States. Keller had been strongly affected by the devastation caused by World War II and the U.S. atomic attacks and was thrilled by the enthusiastic reception she received from the Japanese citizens. She thus grew convinced of her calling to international service, and the AFB leadership agreed. Thrilled by her reception in Japan and always alert to opportunities to promote the U.S. image abroad during the Cold War, the State Department worked with the AFB to fund and facilitate her travels and promote her persona as a representative of Americanism. Seeking renewed purpose and escape, while also believing in her cause, Keller increasingly turned to international travel and advocacy of people with disabilities.

Helen Keller in Japan

A subsequent trip to Japan in 1948 was the catalyst for Keller’s transformation from tourist to semi-official ambassador for the United States. Keller had been strongly affected by the devastation caused by World War II and the U.S. atomic attacks and was thrilled by the enthusiastic reception she received from the Japanese citizens. She thus grew convinced of her calling to international service, and the AFB leadership agreed. Thrilled by her reception in Japan and always alert to opportunities to promote the U.S. image abroad during the Cold War, the State Department worked with the AFB to fund and facilitate her travels and promote her persona as a representative of Americanism. Seeking renewed purpose and escape, while also believing in her cause, Keller increasingly turned to international travel and advocacy of people with disabilities.

By 1957, Keller had traveled to more than 30 countries, attracting huge crowds wherever she went. During her public lectures, meetings with foreign dignitaries and women’s clubs, and frequent visits to schools and other institutions for blind people, she simultaneously scolded governments and philanthropists for their limited efforts and cajoled them to do more. Encouraged by the AFB, the U.S. State Department, her own sense of service, and the delight of international travel, she traveled to countries as widespread as Australia, Brazil, Egypt, India, Mexico, and South Africa. Even in countries that were antagonistic to the U.S., citizens praised Keller enthusiastically. At each location, she gave brief speeches, sometimes aided by her companion Polly Thomson.

Helen Keller Statue at the Capitol

During the years after Macy’s death, Keller strove to redefine herself professionally and personally. By this point, her contacts with Alabama were minimal. Her father had died in 1896, and her mother in 1921. She largely communicated with her brother and sister by letter. From her adopted home of Westport, Connecticut, she developed new friends and venues of expression. Sculptor Jo Davidson became one of the most important of these friends, stimulating her interest in life through intellectual debate and the arts. For example, on a trip to Italy he arranged a tactile “viewing” for Keller of sculptures by Michelangelo and Donatello. Other friendships grew out of the New York world of friend and editor Nella Braddy Henney. With Henney’s assistance, Keller published Journal in 1938, a chronicling of the months after Macy’s death, and Teacher, her memorial to Macy, in 1956. Keller grew to love interacting with these people and valued them for their wit, sharp opinions, and knowledge of the political world. Good friends already knew or learned to finger-spell in order to communicate with Keller, and her speech was easily understood by those accustomed to hearing it. With individuals who did not finger-spell, Keller sometimes relied on her own form of lip reading. She sat very close; and with her left index finger, middle finger, and thumb she touched their nostril, lips, and larynx in order to understand words. At other times, Polly Thomson interpreted on-going conversations by finger-spelling.

Helen Keller Statue at the Capitol

During the years after Macy’s death, Keller strove to redefine herself professionally and personally. By this point, her contacts with Alabama were minimal. Her father had died in 1896, and her mother in 1921. She largely communicated with her brother and sister by letter. From her adopted home of Westport, Connecticut, she developed new friends and venues of expression. Sculptor Jo Davidson became one of the most important of these friends, stimulating her interest in life through intellectual debate and the arts. For example, on a trip to Italy he arranged a tactile “viewing” for Keller of sculptures by Michelangelo and Donatello. Other friendships grew out of the New York world of friend and editor Nella Braddy Henney. With Henney’s assistance, Keller published Journal in 1938, a chronicling of the months after Macy’s death, and Teacher, her memorial to Macy, in 1956. Keller grew to love interacting with these people and valued them for their wit, sharp opinions, and knowledge of the political world. Good friends already knew or learned to finger-spell in order to communicate with Keller, and her speech was easily understood by those accustomed to hearing it. With individuals who did not finger-spell, Keller sometimes relied on her own form of lip reading. She sat very close; and with her left index finger, middle finger, and thumb she touched their nostril, lips, and larynx in order to understand words. At other times, Polly Thomson interpreted on-going conversations by finger-spelling.

In 1955, Keller won an Oscar for her participation in the documentary The Unconquered (also titled Helen Keller in Her Story). In 1964, Pres. Lyndon Johnson awarded her the Congressional Medal of Freedom. When she died on June 1, 1968, at the age of 88, she was one of the most famous people in the world—as she had been since nearly the age of eight. The young girl from Tuscumbia, whose parents had foreseen a grim future for their deaf-blind girl, had literally and figuratively travelled far.

Further Reading

- Foner, Philip S., ed. Helen Keller: Her Socialist Years. New York: International Publishers, 1967.

- Herrmann, Dorothy. Helen Keller: A Life. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1998.

- Lash, Joseph. Helen and Teacher: The Story of Helen Keller and Anne Sullivan Macy. New York: Addison-Wesley, 1980.

- Lowler, Laurie. Helen Keller: Rebellious Spirit. New York: Holiday House, 2001.

- Miller, Sarah. Miss Spitfire: Reaching Helen Keller. New York: Atheneum, 2007.

- Nielsen, Kim E. Helen Keller: Selected Writings. New York: New York University Press, 2005.

- ———. The Radical Lives of Helen Keller. New York: New York University Press, 2004.