Lister Hill

Lister Hill

Lister Hill (1894-1984) was Alabama’s premier lawmaker of the twentieth century. He served in the U.S. Congress for more than 45 years and sponsored 80 pieces of major legislation. His tenure in national office began in 1923, when he was elected to the House of Representatives, and extended until 1969 when he retired from the U.S. Senate. During the 1940s and early 1950s, Hill also dominated the political scene in his home state. Largely owing to his influence, Alabamians elected a House delegation often rated by fellow House members as the best in that body; during this same period, Hill and his protégé, John Sparkman of Huntsville, were ranked in a 1952 study of the U.S. Senate as the fourth-best team in that body. From the New Deal of Franklin Roosevelt until the beginnings of the civil rights era, the Hill machine convinced Alabama’s overwhelmingly white electorate to vote based on their economic needs; as a result, Alabama was often described as the most liberal state in the Deep South.

Lister Hill

Lister Hill (1894-1984) was Alabama’s premier lawmaker of the twentieth century. He served in the U.S. Congress for more than 45 years and sponsored 80 pieces of major legislation. His tenure in national office began in 1923, when he was elected to the House of Representatives, and extended until 1969 when he retired from the U.S. Senate. During the 1940s and early 1950s, Hill also dominated the political scene in his home state. Largely owing to his influence, Alabamians elected a House delegation often rated by fellow House members as the best in that body; during this same period, Hill and his protégé, John Sparkman of Huntsville, were ranked in a 1952 study of the U.S. Senate as the fourth-best team in that body. From the New Deal of Franklin Roosevelt until the beginnings of the civil rights era, the Hill machine convinced Alabama’s overwhelmingly white electorate to vote based on their economic needs; as a result, Alabama was often described as the most liberal state in the Deep South.

John Sparkman

Joseph Lister Hill was born in Montgomery on December 27, 1894, to Luther Leonidas Hill Jr., a prominent and widely known Montgomery physician, and his wife, Lilly Lyons of Mobile. He had a twin sister, Amelie, and a younger brother, Luther Lyons. Hill was reared in Montgomery, graduated from Starke University School there, and earned his undergraduate degree from the University of Alabama in 1914. He then went on to earn a law degree from the University of Alabama and a second from Columbia University at the prodding of his father, who wanted to test Hill’s ability to compete with students at a prestigious northern university.

John Sparkman

Joseph Lister Hill was born in Montgomery on December 27, 1894, to Luther Leonidas Hill Jr., a prominent and widely known Montgomery physician, and his wife, Lilly Lyons of Mobile. He had a twin sister, Amelie, and a younger brother, Luther Lyons. Hill was reared in Montgomery, graduated from Starke University School there, and earned his undergraduate degree from the University of Alabama in 1914. He then went on to earn a law degree from the University of Alabama and a second from Columbia University at the prodding of his father, who wanted to test Hill’s ability to compete with students at a prestigious northern university.

Hill practiced law in Montgomery, with a brief stint in World War I, until the age of 28. In 1922 he was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives from the state’s sparsely populated Second Congressional District, south of Montgomery. Hill owed his victory almost entirely to the influence of his father. Before entering politics, Lister Hill publicly affiliated with the Methodist Church of his paternal forefathers, thus forsaking the Catholic faith in which, at his mother’s insistence, he had been reared. He also carefully hid the fact that his mother was partly of Jewish ancestry. In February 1928 he married Henrietta Fontaine McCormick of Eufaula; they had two children, Henrietta and Luther Lister.

During his 15 years in the House of Representatives, Hill became an ardent follower of Pres. Franklin D. Roosevelt, who exemplified to this young member of the Alabama gentry the concept of the aristocrat as Democrat. Under Roosevelt’s spell, Hill became an active New Dealer, supporting government programs for public works, employment, rural electrification and telephone service, and subsidies for cutbacks in agricultural production. Less enthusiastically at first, he sponsored the House version of the bill that created the Tennessee Valley Authority, envisioned by Senator George Norris of Nebraska, that eventually transformed the geography and economy of north Alabama with lakes, barge traffic, fertilizer plants, new industries, and cheap electricity.

Lister Hill Sworn into Senate

In 1938 Hill was elected to the U.S. Senate to fill the seat of Hugo Black, who had been appointed by Roosevelt to the U.S. Supreme Court. Hill defeated aging former senator J. Thomas Heflin, who was backed by Alabama’s so-called Big Mules, leaders of business and agriculture who strongly opposed Roosevelt’s proposal to limit the work week to 44 and then 40 hours and to raise the minimum wage to 25 and then 40 cents. Organized labor, voters in the Tennessee Valley, and white, working-class Alabamians devoted to FDR rallied behind Hill, who favored this legislation. His victory helped to spur passage of the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, which brought about immediate pay raises for millions and ended child labor.

Lister Hill Sworn into Senate

In 1938 Hill was elected to the U.S. Senate to fill the seat of Hugo Black, who had been appointed by Roosevelt to the U.S. Supreme Court. Hill defeated aging former senator J. Thomas Heflin, who was backed by Alabama’s so-called Big Mules, leaders of business and agriculture who strongly opposed Roosevelt’s proposal to limit the work week to 44 and then 40 hours and to raise the minimum wage to 25 and then 40 cents. Organized labor, voters in the Tennessee Valley, and white, working-class Alabamians devoted to FDR rallied behind Hill, who favored this legislation. His victory helped to spur passage of the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, which brought about immediate pay raises for millions and ended child labor.

Hill entered the Senate at the age of 43 as one of the five youngest members in that body. Initially his future appeared promising—he quickly rose to the post of Democratic whip, second to Majority Leader Alben Barkley in managing the legislative docket. There was even talk that Hill might be the first southerner, representing a southern state, elected president of the United States in the twentieth century. But in nominating Roosevelt for a third term at the Democratic convention of 1940, Hill became a national laughingstock when a huge radio audience, as widely reported in the anti-Roosevelt press, jeered at his southern accent and florid oratory.

1948 Democratic National Convention

His White House hopes were to be ended, however, by a much more serious issue: in choosing political survival in Alabama, Hill opposed every civil rights measure that came before Congress during his long tenure in office. In addition to signing the “Southern Manifesto” opposing school integration in 1956, he voted against the Civil Rights Acts of 1957, 1960, and 1964 and the 1965 Voting Rights Act, all of which aimed to strengthen voting rights, and the 1968 Civil Rights Act, which addressed housing discrimination. He handily turned back challengers in four Democratic primaries (at the time equivalent to election), defeating James Simpson in 1944, Lawrence McNeil in 1950, and John Crommelin in 1956 and 1962. Despite his opposition to civil rights legislation, Hill was not among the half of the Alabama delegates to the 1948 Democratic National Convention who walked out in protest of the nomination of pro-civil rights candidate Harry Truman. These men would go on to form the Dixiecrat faction, but Hill remained aligned with the national Democratic Party. Although not vulnerable to those who used race to lure white Alabamians away from Democratic loyalty, Hill narrowly won his last campaign in the general election of 1962 against an openly Republican candidate, James D. Martin of Gadsden.

1948 Democratic National Convention

His White House hopes were to be ended, however, by a much more serious issue: in choosing political survival in Alabama, Hill opposed every civil rights measure that came before Congress during his long tenure in office. In addition to signing the “Southern Manifesto” opposing school integration in 1956, he voted against the Civil Rights Acts of 1957, 1960, and 1964 and the 1965 Voting Rights Act, all of which aimed to strengthen voting rights, and the 1968 Civil Rights Act, which addressed housing discrimination. He handily turned back challengers in four Democratic primaries (at the time equivalent to election), defeating James Simpson in 1944, Lawrence McNeil in 1950, and John Crommelin in 1956 and 1962. Despite his opposition to civil rights legislation, Hill was not among the half of the Alabama delegates to the 1948 Democratic National Convention who walked out in protest of the nomination of pro-civil rights candidate Harry Truman. These men would go on to form the Dixiecrat faction, but Hill remained aligned with the national Democratic Party. Although not vulnerable to those who used race to lure white Alabamians away from Democratic loyalty, Hill narrowly won his last campaign in the general election of 1962 against an openly Republican candidate, James D. Martin of Gadsden.

Through his long service in the Senate, Hill became one of that body’s inner circle, rising to the powerful position of chair of its Labor and Public Welfare Committee. Always inspired by his father’s profession, Hill co-sponsored the 1946 Hill-Burton Act, which provided federal funding for hospital construction, especially in rural areas, and which had been crafted by the medical establishment to counter President Harry Truman’s proposed national health insurance. Through his chairmanship, Hill became the leading proponent of federal funding of medical research, by which billions of dollars were eventually allocated to the National Institutes of Health. He also played a crucial role in spreading medical knowledge worldwide by advocating the creation in 1959 of a new National Institute for International Medical Research. Additionally, he and a fellow Alabamian in the House of Representatives, Carl Elliott of Jasper, sponsored the Library Services Act of 1956, which authorized federal funding for libraries. They also sponsored a much larger, path-breaking measure, the National Defense Education Act of 1958, which committed the federal government to massive assistance in improving education and which continues to benefit millions of young Americans who rely on college loans to achieve their career goals.

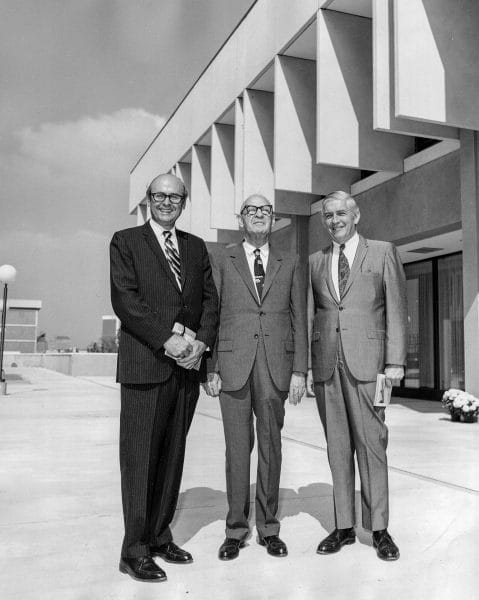

Lister Hill Library Dedication

In 1962, Hill faced a serious challenge from the candidate of the newly emerging Republican Party, James D. Martin. Hill won the election with only one percnt of the vote. In 1968, at the age of 74, Hill retired rather than face another grueling campaign. Even longtime political enemies conceded the value of his contributions to the citizens of Alabama. The New York Times described Hill as a politician “trapped by the racial history of [his] region . . . who [nevertheless] dared to be progressive on every issue except civil rights.” The Times concluded that he had “done more for the health of Americans in modern times than any man outside the medical profession.” Hill’s Alabama supporters pointed out that his legislative achievements in health, education, the creation of the Tennessee Valley Authority, and the establishment of numerous military bases in the state all benefited blacks as well as whites. One North Carolina newspaper predicted that Hill’s name would grace historic legislation “when George Wallace is reduced to a pathetic footnote in history.” But another North Carolina editor offered the more prescient observation that “the Alabama of George Wallace could not produce another Lister Hill. . . . [I]f somehow one appeared, the state would not elect him.”

Lister Hill Library Dedication

In 1962, Hill faced a serious challenge from the candidate of the newly emerging Republican Party, James D. Martin. Hill won the election with only one percnt of the vote. In 1968, at the age of 74, Hill retired rather than face another grueling campaign. Even longtime political enemies conceded the value of his contributions to the citizens of Alabama. The New York Times described Hill as a politician “trapped by the racial history of [his] region . . . who [nevertheless] dared to be progressive on every issue except civil rights.” The Times concluded that he had “done more for the health of Americans in modern times than any man outside the medical profession.” Hill’s Alabama supporters pointed out that his legislative achievements in health, education, the creation of the Tennessee Valley Authority, and the establishment of numerous military bases in the state all benefited blacks as well as whites. One North Carolina newspaper predicted that Hill’s name would grace historic legislation “when George Wallace is reduced to a pathetic footnote in history.” But another North Carolina editor offered the more prescient observation that “the Alabama of George Wallace could not produce another Lister Hill. . . . [I]f somehow one appeared, the state would not elect him.”

Lister Hill died in Montgomery on December 20, 1984, a few days short of his 90th birthday.

Further Reading

- Flynt, Wayne. Alabama in the Twentieth Century. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2004.

- Hamilton, Virginia Van der Veer. Lister Hill: Statesman from the South. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1987. Reprinted in paperback by The Library of American Classics, Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2004.

- ———. Hugo Black: The Alabama Years. 1972. Reprint, Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1982.