James Adair

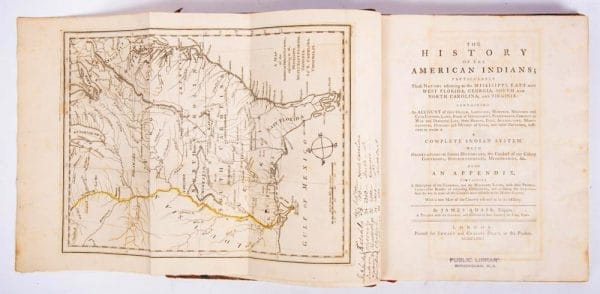

James Adair (ca. 1709-ca. 1775) authored what is arguably the most significant eighteenth-century work on the southeastern Indians: The History of the American Indians . . ., published in London in 1775. The book, a cultural and historical study of the Catawbas, Cherokees, Creeks, Choctaws, and Chickasaws Indians, is based on Adair’s first-hand observations derived from his 40-year career as a deerskin trader among several southeastern Indian tribes.

The History of the American Indians

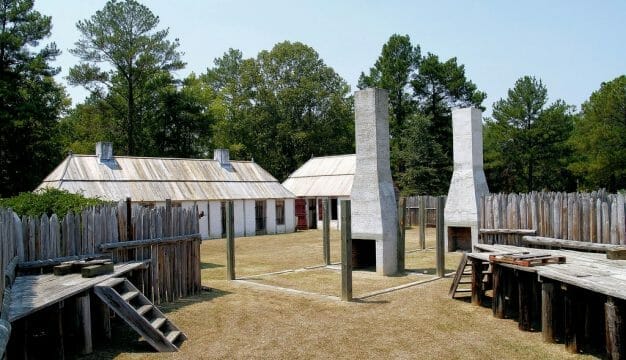

Adair is widely believed to have been born in County Antrim, Ireland, in 1709, although no evidence to support the contention exists. In his book, Adair dates his entry into the deerskin trade at 1735, when he briefly traded with the Catawba Indians. He quickly moved to the more lucrative Cherokee trade and soon afterward began trading with the Chickasaws. Adair entered the trade at a dangerous time in international relations. The French in New Orleans and Mobile (then part of the French colony of Louisiana) were attempting to gain Indian allies at the expense of the British, whose colonies of South Carolina and Georgia were aggressively pursuing trade and diplomatic alliances with the major southern tribes, particularly the Cherokees, Creeks, and Chickasaws. The Spanish in Florida likewise resented British incursions into their established territory, as well as their attempts to enlist Indian allies as auxiliaries against Spanish settlements. Adair, a man of education and ability, quickly caught the attention of those in power, and he was employed by the governor of South Carolina to entice a band of Chickasaw Indians to resettle at New Windsor, near Fort Moore on the Savannah River, to help defend the post—and colony—from attack by Indian allies of the French or Spanish.

The History of the American Indians

Adair is widely believed to have been born in County Antrim, Ireland, in 1709, although no evidence to support the contention exists. In his book, Adair dates his entry into the deerskin trade at 1735, when he briefly traded with the Catawba Indians. He quickly moved to the more lucrative Cherokee trade and soon afterward began trading with the Chickasaws. Adair entered the trade at a dangerous time in international relations. The French in New Orleans and Mobile (then part of the French colony of Louisiana) were attempting to gain Indian allies at the expense of the British, whose colonies of South Carolina and Georgia were aggressively pursuing trade and diplomatic alliances with the major southern tribes, particularly the Cherokees, Creeks, and Chickasaws. The Spanish in Florida likewise resented British incursions into their established territory, as well as their attempts to enlist Indian allies as auxiliaries against Spanish settlements. Adair, a man of education and ability, quickly caught the attention of those in power, and he was employed by the governor of South Carolina to entice a band of Chickasaw Indians to resettle at New Windsor, near Fort Moore on the Savannah River, to help defend the post—and colony—from attack by Indian allies of the French or Spanish.

Embroiled in Controversy

When King George’s War (1744-48) broke out among the major European powers, Adair became embroiled in one of the most interesting and controversial episodes of his long career—an attempt by South Carolina to lure the Choctaw Indians from their French alliance by initiating a trade partnership with them. The plan was the brainchild of South Carolina governor James Glen and others, who saw in it the potential to both undermine what they perceived as expanding French influence among the Indians and make enormous personal profits. Among other activities, Adair worked (under instructions from Glen) to assist the pro-English Choctaw faction in their efforts against the French. The complicated gambit, which ultimately failed, split the Choctaw towns and resulted in a bitter and costly civil war. Adair’s angry condemnation of the underhanded actions by Glen and his trading partners, who failed miserably in their attempts to supply the Choctaw, almost landed the trader in the Charles Town jail, and effectively ended his influence as an advisor and agent. In what was likely a botched attempt to gather evidence against Glen and his partners, Adair visited the French at Fort Toulouse after the war ended. In South Carolina, it was widely reported that he had defected to the enemy, although the French arrested him and were on the verge of sending him to prison in Mobile when he managed to escape. Patronless and deeply in debt, Adair retired to the backcountry and began his history of the failed “Choctaw Revolt” with an eye to clearing his name.

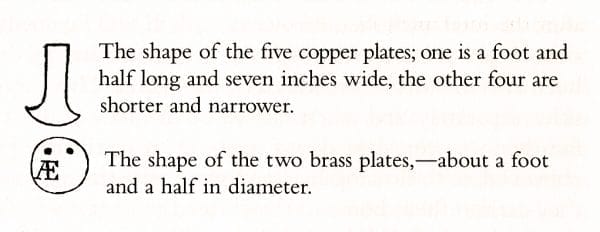

Tukabatchee Ceremonial Decoration

Adair seems to have spent the next decade among the western Chickasaw towns and at New Windsor, likely spending some of his time writing his book. In time, Adair’s reputation was restored, and he was appointed to serve as a lieutenant in charge of leading Chickasaw warriors against the Cherokee during the Cherokee War with South Carolina in 1760. By the time of the cession of French Louisiana to Great Britain in 1763, Adair was widely recognized as one of the most reputable and experienced backcountry traders. He gave up trading in the early 1770s to pursue publication of his book. His obvious intellect and knowledge of the southern tribes won him the assistance of a number of prominent men, including Joseph Galloway, then the speaker of the Pennsylvania assembly; Elias Boudinot, who would soon serve as president of the Continental Congress, and Benjamin Franklin, whom he met in London and who was then acting as colonial agent for several colonies. Franklin provided him with publishing advice and a letter of introduction to a leading London publishing house, which published Adair’s book in 1775. By that time, Adair had returned to America, and his last known activity was his participation in another controversy: he was a signatory on a deed by which Georgia plantation owner Jonathan Bryan attempted to lease a sizeable parcel of land in East Florida from the Creek Indians. Adair’s final years, including the actual date of his death, are a mystery, and no records of his existence after 1775 have been uncovered.

Tukabatchee Ceremonial Decoration

Adair seems to have spent the next decade among the western Chickasaw towns and at New Windsor, likely spending some of his time writing his book. In time, Adair’s reputation was restored, and he was appointed to serve as a lieutenant in charge of leading Chickasaw warriors against the Cherokee during the Cherokee War with South Carolina in 1760. By the time of the cession of French Louisiana to Great Britain in 1763, Adair was widely recognized as one of the most reputable and experienced backcountry traders. He gave up trading in the early 1770s to pursue publication of his book. His obvious intellect and knowledge of the southern tribes won him the assistance of a number of prominent men, including Joseph Galloway, then the speaker of the Pennsylvania assembly; Elias Boudinot, who would soon serve as president of the Continental Congress, and Benjamin Franklin, whom he met in London and who was then acting as colonial agent for several colonies. Franklin provided him with publishing advice and a letter of introduction to a leading London publishing house, which published Adair’s book in 1775. By that time, Adair had returned to America, and his last known activity was his participation in another controversy: he was a signatory on a deed by which Georgia plantation owner Jonathan Bryan attempted to lease a sizeable parcel of land in East Florida from the Creek Indians. Adair’s final years, including the actual date of his death, are a mystery, and no records of his existence after 1775 have been uncovered.

Development of the Book

Adair’s career as an Indian trader and agent for South Carolina would make him worthy of historic attention, but it is his book that sets him apart from other notables of the day. By the time the work was published, he had developed it from an event-driven narrative designed to expose his political enemies and salvage his reputation into a complex examination of the origins of the American Indians. The book details important events between the 1740s and the 1770s from the viewpoint of a backcountry settler and merchant, including commentary on land grants and settlement patterns in West Florida and British policies regarding the Indians. It is particularly valuable in documenting the bitter struggle between British and French colonists for control of Indian allies and thus, the southern backcountry. More importantly, Adair’s discourse on the origin of the American Indians is the most complete and systematic attempt by an American to discuss the question up to that time—a question of prime importance among intellectuals of Adair’s day. His central thesis, which dominates the text and has subsequently caused many to dismiss the contents, includes 23 arguments purporting to demonstrate that the American Indians are of Hebrew descent (the Lost Tribes of Israel). But as modern scholars have observed, although Adair’s central thesis is flawed, the evidence he presents and his sincere effort at comparative analysis of cultures has resulted in an astounding work on southeastern Indian culture, examining in detail such topics as gender roles, religion, warfare, marriage customs, and language. More importantly, Adair’s intense focus on matters of ritual purity has influenced the interpretative framework developed by modern anthropologists and ethnohistorians. Moreover, although Adair wrote in emotional and condemnatory tones regarding his political enemies, for the most part, his characterization of the events is largely confirmed by other sources.

Further Reading

- Braund, Kathryn E. Holland. “James Adair: His Life and History.” In James Adair, The History of the American Indians. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2005, pp. 1-53.

- Hudson, Charles. “James Adair as Anthropologist.” Ethnohistory 24 (Fall 1977): 311–28.