Beef Cattle Industry

Livestock Market

Alabama’s modern cattle industry is one of the pillars of agriculture in the state. Since the introduction of cattle to North America by the Spanish, breeds, ranching methods, and ownership have undergone numerous transformations. Diverse practices and practitioners all contributed to the development of cattle raising in Alabama, and today it is the most common agricultural activity among farmers in Alabama and around the country. Cattle can be found in every Alabama county, with Montgomery and Cullman Counties having the highest number, and beef is valued at around $524 million in the state as a whole.

Livestock Market

Alabama’s modern cattle industry is one of the pillars of agriculture in the state. Since the introduction of cattle to North America by the Spanish, breeds, ranching methods, and ownership have undergone numerous transformations. Diverse practices and practitioners all contributed to the development of cattle raising in Alabama, and today it is the most common agricultural activity among farmers in Alabama and around the country. Cattle can be found in every Alabama county, with Montgomery and Cullman Counties having the highest number, and beef is valued at around $524 million in the state as a whole.

Cattle are not indigenous to the Western Hemisphere. Although feral cattle likely ventured from coastal areas into modern-day Alabama ahead of permanent European settlers, in the late sixteenth century Spanish missionaries first introduced the practice of cattle raising to the American Indians of the interior Southeast. Domestic cattle raising was likely already underway in Alabama in the late seventeenth century. The first documentation of the practice, however, appears in 1701 from French colonial records from Dauphin Island and other Mobile Bay settlements. Within a generation, French colonial commerce boasted a thriving cattle-raising business, and, like their Spanish predecessors, French missionaries and settlers traded their knowledge and stock with local Indian tribes. The eighteenth century witnessed a dramatic increase in cattle raising among Indian nations in the Southeast, with the Cherokees of northeastern Alabama adapting the practices of European settlers in the western Carolinas.

Cattle Auction

By the time of the American Revolution, some residents of the Mobile area and several prominent residents of local Indian villages owned herds numbering in the hundreds. By the time of Alabama’s statehood in 1819, however, cattle ranching had come to be dominated by the Anglo-American settlers who flooded into the region, bringing with them a system of ranching developed in the piney woods of the Carolinas. Like the French and Spanish settlers, Anglo-Americans took advantage of the vast open spaces and a comparatively sparse population. Farmers fenced in their crops and allowed livestock to roam freely in a system known as open-range herding. Cattle were periodically corralled and identified with brands or marks, and drovers transported herds of cattle to markets in Mobile, on the east coast, or in blossoming interior towns. In the first half of the nineteenth century, southwest Alabama, with its plentiful canebrakes (dense thickets of cane with edible shoots) and sawgrass stands became the territory’s and state’s primary cattle-herding region.

Cattle Auction

By the time of the American Revolution, some residents of the Mobile area and several prominent residents of local Indian villages owned herds numbering in the hundreds. By the time of Alabama’s statehood in 1819, however, cattle ranching had come to be dominated by the Anglo-American settlers who flooded into the region, bringing with them a system of ranching developed in the piney woods of the Carolinas. Like the French and Spanish settlers, Anglo-Americans took advantage of the vast open spaces and a comparatively sparse population. Farmers fenced in their crops and allowed livestock to roam freely in a system known as open-range herding. Cattle were periodically corralled and identified with brands or marks, and drovers transported herds of cattle to markets in Mobile, on the east coast, or in blossoming interior towns. In the first half of the nineteenth century, southwest Alabama, with its plentiful canebrakes (dense thickets of cane with edible shoots) and sawgrass stands became the territory’s and state’s primary cattle-herding region.

The Civil War

Although most common in south Alabama, cattle raising had spread across the state by the outbreak of the Civil War. Although pork was more popular than beef in the typical southern diet, most planters and small farmers in Alabama found plenty of reasons to keep cattle in addition to their hogs. Cattle served as draft animals, as sources of meat and dairy products, as producers of fertilizer, and as suppliers of leather, tallow, and other products. On the plantations of the Black Belt and the Tennessee Valley, slaves most often cared for cattle and other livestock, and some became skilled cattlemen. Large planters and “gentleman farmers” were most responsible for the introduction and expansion of purebred herds of modern British breeds such as Herefords, Shorthorns, and Devons, which were used to improve bloodlines in common herds and as display animals at local fairs and livestock shows.

By the mid-nineteenth century, cotton production had emerged as the primary agricultural pursuit in Alabama, a development that caused a corresponding decline in cattle raising. The Civil War took a further toll on Alabama’s cattle herds as animals were sold off, consumed by hungry families on the homefront or confiscated by the military. For the remainder of the nineteenth century and into the early twentieth century, Alabama’s cattle industry stagnated. Furthermore, with the almost universal use of horses and mules as work stock and the increasing availability of mass-produced leather, candles, and other cattle-derived products, cattle gradually ceased to be the multi-purpose animals they had been during much of the nineteenth century. By the turn of the twentieth century, cattle served mostly as a source of milk and meat.

Foundations of Modern Cattle-Raising

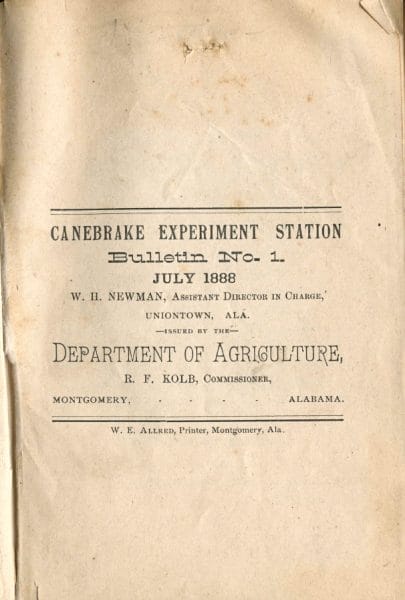

Canebrake Experiment Station Bulletin

Developments during this period laid the foundation for what would become the modern cattle-raising industry. One of these harbingers was the movement to close the open range. Influential planters, who disliked the expense of fencing in hundreds of acres of crops and who feared their purebred cows would breed with the “scrub” bulls belonging to less “progressive” neighbors, had begun to voice opposition to the open-range tradition prior to the war. Responding to pressure from powerful planters, in 1866 the Alabama legislature designated the state’s first closed-range area, the Canebrake Agricultural District, in the Black Belt, a heavily cultivated plantation area from which all cattle and hogs were banned. Open-range herding continued in South Alabama and in some highland areas well into the 1900s, but the practice ended gradually as Progressive-era ideas took hold in livestock raising. “Stock law” controversies reflected socioeconomic divisions in the state, as poor farmers and tenants, the ones whose small landholdings or lack of land altogether made them most likely to benefit from the open-range tradition, found themselves in opposition to planters, middle-class farmers, and land-owning industrialists. Small and landless farmers viewed the stock law as a method used by the agricultural elite to cast the poor into economic dependence, while larger farmers and planters justified stock laws with arguments for agricultural improvement and soil conservation.

Canebrake Experiment Station Bulletin

Developments during this period laid the foundation for what would become the modern cattle-raising industry. One of these harbingers was the movement to close the open range. Influential planters, who disliked the expense of fencing in hundreds of acres of crops and who feared their purebred cows would breed with the “scrub” bulls belonging to less “progressive” neighbors, had begun to voice opposition to the open-range tradition prior to the war. Responding to pressure from powerful planters, in 1866 the Alabama legislature designated the state’s first closed-range area, the Canebrake Agricultural District, in the Black Belt, a heavily cultivated plantation area from which all cattle and hogs were banned. Open-range herding continued in South Alabama and in some highland areas well into the 1900s, but the practice ended gradually as Progressive-era ideas took hold in livestock raising. “Stock law” controversies reflected socioeconomic divisions in the state, as poor farmers and tenants, the ones whose small landholdings or lack of land altogether made them most likely to benefit from the open-range tradition, found themselves in opposition to planters, middle-class farmers, and land-owning industrialists. Small and landless farmers viewed the stock law as a method used by the agricultural elite to cast the poor into economic dependence, while larger farmers and planters justified stock laws with arguments for agricultural improvement and soil conservation.

While stock laws helped transform the countryside, state and federal governmental agencies played a significant role in modernizing cattle raising in the Lower South, as they had already done in the Midwest and Upper South. In 1872, the Alabama legislature established the state’s land-grant university, the Agricultural and Mechanical College of Alabama, at Auburn, and the institution would serve as both a catalyst for and a messenger of agricultural progressivism in the succeeding decades. The school’s Canebrake Experiment Station, founded in 1885 and partially funded with federal money from the Hatch Act of 1887, provided Alabama agriculturists with scientific information on forage crops, pasture grasses, and various facets of cattle feeding and breeding.

Additionally, a joint federal and state effort was implemented in 1906 to do away with, or at least control, the harmful and costly Texas fever tick. It required farmers to participate in eradication efforts conducted by government agents, or “tick inspectors,” who oversaw the construction of dipping vats, in-ground structures in which cattle were “dipped” in a chemical solution designed to kill the ticks. Like the stock laws, the tick eradication program proved controversial and reflected socioeconomic divisions. Many farmers, especially poor and landless ones, resented both the governmental intrusion and the expense and effort required to drive their cattle to designated dipping vats, and some responded by dynamiting vats or intimidating tick inspectors.

The Cooperative Extension System

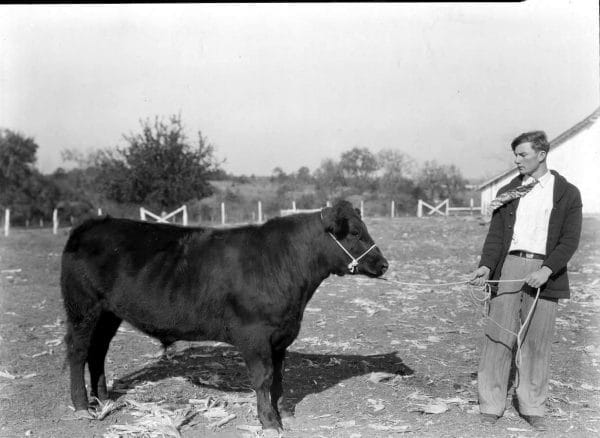

Angus Steer

In 1914, a joint federal and state effort established the Cooperative Extension System, which was coordinated through the land-grant universities. Following the massive boll weevil infestation that began in 1910, the program furthered progressive goals of agricultural diversity by placing university-trained extension agents in each county. During the 1910s and 1920s, the changes fostered and implemented by these agencies coalesced to produce a modern, Midwestern-style of cattle raising in the Black Belt characterized by purebred cattle, enclosed fields of pasture and hay grass, and wintertime feeding of hay and grains.

Angus Steer

In 1914, a joint federal and state effort established the Cooperative Extension System, which was coordinated through the land-grant universities. Following the massive boll weevil infestation that began in 1910, the program furthered progressive goals of agricultural diversity by placing university-trained extension agents in each county. During the 1910s and 1920s, the changes fostered and implemented by these agencies coalesced to produce a modern, Midwestern-style of cattle raising in the Black Belt characterized by purebred cattle, enclosed fields of pasture and hay grass, and wintertime feeding of hay and grains.

During the first half of the twentieth century, the Black Belt became Alabama’s unrivaled leader in cattle raising, as more and more planters reacted to boll-weevil infestation and declining cotton prices by switching to cattle. The opening of Union Stock Yards in Montgomery in 1918 provided central Alabama cattlemen with a much-needed local market, and the Depression-era establishment of auction markets in the Black Belt—beginning with Selma in 1929—supplied even more outlets for cattle sales. New Deal programs in the 1930s further boosted the region’s cattle industry by providing subsidies to help farmers convert row-crop acreage to pasturage and hayfields.

These developments only hastened a trend already underway in the Black Belt; in other parts of the state, however, they proved almost revolutionary in their effects on agriculture. From the hills in the northeast to the piney woods in the southwest, Alabama farmers altered their farming practices in accordance with federal mandates and market dictates. Cotton acreage allotments, extension service calls for diversification, the founding of the Alabama Cattlemen’s Association during World War II, rising beef prices, and more plentiful markets for livestock all contributed to increasing numbers of cattle herds in the state. An increased emphasis on purebreds, such as Hereford, Angus, and Shorthorn, improved the quality and value of Alabama herds.

The Postwar Years

The boom in Alabama’s cattle industry continued into the postwar years, with the cattle industry supplanting cotton as the state’s most lucrative agricultural activity in the early 1950s. Black Belt cattlemen continued to lead the state in beef cattle production—and in gaining positions of influence within the Alabama Cattlemen’s Association—through the 1960s. The mid-1960s through the 1970s saw a stagnation of the cattle industry in the Black Belt, but this was countered by a boom in other regions of the state, most notably the Tennessee Valley, the Wiregrass, and especially the Appalachian counties of northeast Alabama. There, cattle numbers more than doubled in the period between 1959 and 1974.

Alabama Cattlemen’s Association

In 2016, more than 17,000 Alabama farmers sold $558 million worth of cattle and calves, ranking cattle second only to poultry in terms of agricultural sales. There are more than 1.2 million cattle in the state, and the cattle industry overall is worth $2.5 billion to the state. The staying power of cattle farming, and much of its growth over the past half century, can be attributed to its easy fit with the demands of part-time farming. Beef cattle require only minimal supervision and care in the Deep South for much of the year. Perhaps of most importance to many part-time, or hobby, ranchers is cattle raising’s link to an agrarian tradition that has become increasingly threatened in the modern world.

Alabama Cattlemen’s Association

In 2016, more than 17,000 Alabama farmers sold $558 million worth of cattle and calves, ranking cattle second only to poultry in terms of agricultural sales. There are more than 1.2 million cattle in the state, and the cattle industry overall is worth $2.5 billion to the state. The staying power of cattle farming, and much of its growth over the past half century, can be attributed to its easy fit with the demands of part-time farming. Beef cattle require only minimal supervision and care in the Deep South for much of the year. Perhaps of most importance to many part-time, or hobby, ranchers is cattle raising’s link to an agrarian tradition that has become increasingly threatened in the modern world.

Further Reading

- Blevins, Brooks. Cattle in the Cotton Fields: A History of Cattle Raising in Alabama. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1998.

- Jordan, Terry G. North American Cattle-Ranching Frontiers: Origins, Diffusion, and Differentiation. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1993.