British West Florida

East and West Florida, 1763

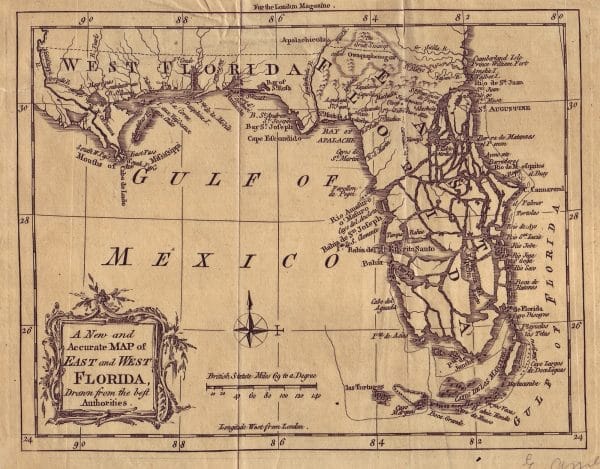

In the Seven Years’ War (1754, 1756-1763), British forces soundly defeated those of the Spanish and the French. One result was a new British province, West Florida, fashioned in 1763 from what had been enemy possessions in what are now Mississippi, Louisiana, Alabama, and the Florida panhandle. Territorially, British West Florida included more than half of the present state of Alabama. Its first northern boundary was just below modern Montgomery, but as a result of lobbying by West Florida’s first governor, George Johnstone, the boundary was expanded in 1764 to below present-day Birmingham. The only towns of significant size in West Florida were its two ports on the Gulf of Mexico: Pensacola, British West Florida’s capital, and Mobile, which had been the most significant French post on the Gulf. Apart from a scattering of traders, the population surrounding the British settlements was primarily Native American, particularly Creeks, Choctaws, and Chickasaws.

East and West Florida, 1763

In the Seven Years’ War (1754, 1756-1763), British forces soundly defeated those of the Spanish and the French. One result was a new British province, West Florida, fashioned in 1763 from what had been enemy possessions in what are now Mississippi, Louisiana, Alabama, and the Florida panhandle. Territorially, British West Florida included more than half of the present state of Alabama. Its first northern boundary was just below modern Montgomery, but as a result of lobbying by West Florida’s first governor, George Johnstone, the boundary was expanded in 1764 to below present-day Birmingham. The only towns of significant size in West Florida were its two ports on the Gulf of Mexico: Pensacola, British West Florida’s capital, and Mobile, which had been the most significant French post on the Gulf. Apart from a scattering of traders, the population surrounding the British settlements was primarily Native American, particularly Creeks, Choctaws, and Chickasaws.

The onset of the American Revolution in 1775 hobbled the growth of population and the expansion of trade that usually followed. American privateers further hampered the flow of goods and immigrants to British territories. One even dared to enter Mobile’s harbor and seize a loaded merchant vessel. The one population group that did increase during the Revolution was the Tories. Looking for a refuge from persecution, Tories found the province an especially attractive haven because the British crown offered free land in West Florida as a reward to anyone who met any of three criteria: proven Loyalism, service in the Seven Years’ War, or head of household. Despite this influx, even at its height in 1779, it is unlikely that the number of white inhabitants of West Florida exceeded 6,000.

George Johnstone

Throughout the colony’s existence the military comprised a major component of the population. In 1763 the 22nd Infantry Regiment occupied Mobile’s Fort Condé, established by the French in 1702, and renamed it Fort Charlotte to honor Britain’s queen. At the time, Mobile was home to 40 French families of perhaps 200 individuals. British military leaders thought that a military presence might preserve order if the port’s French inhabitants grew restless under British rule. In fact the residents accepted British authority without resistance, but also without noticeable enthusiasm.

George Johnstone

Throughout the colony’s existence the military comprised a major component of the population. In 1763 the 22nd Infantry Regiment occupied Mobile’s Fort Condé, established by the French in 1702, and renamed it Fort Charlotte to honor Britain’s queen. At the time, Mobile was home to 40 French families of perhaps 200 individuals. British military leaders thought that a military presence might preserve order if the port’s French inhabitants grew restless under British rule. In fact the residents accepted British authority without resistance, but also without noticeable enthusiasm.

The many entrepreneurs who flocked to West Florida to make fortunes through trade with the Spanish empire found frustration, but Native Americans of West Florida clamored for the products of England’s factories and New England’s distilleries. Native Americans exchanged deerskins for muskets, textiles, hardware, and rum. Although large vessels could not enter Mobile harbor with ease, a 130-ton vessel arrived annually to ship skins and furs to Britain, and the many rivers flowing into Mobile Bay provided easy access to the interior. The Creeks and Choctaws were at war for a decade prior to the American Revolution, so no doubt their supply of hides for trading was low. Even so, merchant houses of Mobile, and the partnership of James McGillivray, John Miller, William Struthers, and Peter Swanson in particular, exported tens of thousands of skins each year.

Land was either cheap or free in West Florida, so many immigrants were able to acquire large holdings and establish plantations worked by slaves. Planters produced indigo, tobacco, and rice, but the most profitable export was timber products. Around Mobile, and along adjacent rivers, including the Tensaw, Dog, Fowl, and Fish, the light soil made cattle raising and the production of tar, turpentine, and potash the most common pursuits.

Bernardo de Gálvez

During the first three years of the American Revolution, West Florida remained uninvolved and unmolested, even though it spurned overtures from the Continental Congress, and its legislature and council proudly professed loyalty to King George III. The apparent immunity of the province disappeared in 1778 when James Willing of the U.S. Navy launched a raid through the province’s back door, the Mississippi River. Meeting almost no resistance, his force of about 100 men destroyed many plantations in the colony’s western districts. Although his success was short-lived, and Willing soon saw the inside of a British jail, his achievement alerted the British crown to West Florida’s vulnerability. Two regiments of Loyalists from Pennsylvania and Maryland and a German regiment from Waldeck arrived in January 1779 to bolster the 16th Infantry Regiment, until then the sole regular unit available during the Revolution for the defense of the colony.

Bernardo de Gálvez

During the first three years of the American Revolution, West Florida remained uninvolved and unmolested, even though it spurned overtures from the Continental Congress, and its legislature and council proudly professed loyalty to King George III. The apparent immunity of the province disappeared in 1778 when James Willing of the U.S. Navy launched a raid through the province’s back door, the Mississippi River. Meeting almost no resistance, his force of about 100 men destroyed many plantations in the colony’s western districts. Although his success was short-lived, and Willing soon saw the inside of a British jail, his achievement alerted the British crown to West Florida’s vulnerability. Two regiments of Loyalists from Pennsylvania and Maryland and a German regiment from Waldeck arrived in January 1779 to bolster the 16th Infantry Regiment, until then the sole regular unit available during the Revolution for the defense of the colony.

These reinforcements proved no match for the dashing and resourceful Bernardo de Gálvez , Spanish governor of Louisiana, who invaded West Florida as soon as he could after Spain declared war on Britain on June 21, 1779. Having conquered small British garrisons on the Mississippi, Gálvez and his commander José Manuel de Ezpeleta laid siege to Mobile’s Fort Charlotte in March 1780. The commandant of the crumbling fort, Elias Durnford, had in his command a few regulars, a number of sailors, two dozen dragoons of the West Florida Royal Foresters, some volunteers, and armed slaves supplied by local citizens. All told he had 304 defenders to pit against almost 2,000 besiegers. After Spanish artillery smashed breaches in Fort Charlotte’s walls, Durnford surrendered on the 13th day of the siege. Gálvez acknowledged the spirit of Durnford’s defense by allowing him the full honors of war, that is, he allowed the defenders to march out with drums beating and colors flying before they surrendered their weapons to the victors.

For the next year the new governor of Mobile, José de Ezpeleta, attacked the Pensacola garrison and Britain’s Native American allies from Mobile. Pensacola was West Florida’s last stronghold. It surrendered to Gálvez in May 1781, thus ending British rule in West Florida .

Further Reading

- Bartram, William. Travels through North and South Carolina, Georgia, East and West Florida. 1791. Reprint, New York: Penguin, 1988.

- Braund, Kathryn H. Deerskins and Duffels: The Creek Indian Trade with Anglo-America, 1685-1815. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1993.

- Braund, Kathyrn H., ed. The Attention of a Traveller: Essays on William Bartram’s “Travels” and Legacy. Tuscaloosa, Ala.: University of Alabama Press, 2022.

- Bunn, Mike. Fourteenth Colony: The Forgotten Story of the Gulf South During America’s Revolutionary Era. Montgomery: NewSouth Books, 2020.

- Fabel, Robin F.A. The Economy of British West Florida, 1763-1783. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1988.

- Hamilton, Peter J. Colonial Mobile. 1910. Reprint, Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1976.

- Johnson, Cecil. British West Florida, 1763-1783. Hamden, Conn.: Archon, 1971.

- Rea, Robert R. Major Robert Farmar of Mobile. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1990.

- Romans, Bernard. A Concise Natural History of East and West Florida. Edited by Kathryn Braund. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1999.

- Starr, J Barton. Tories, Dons, and Rebels: The American Revolution in British West Florida. Gainesville: University Presses of Florida, 1976.