William Crawford Gorgas

Gorgas, William Crawford

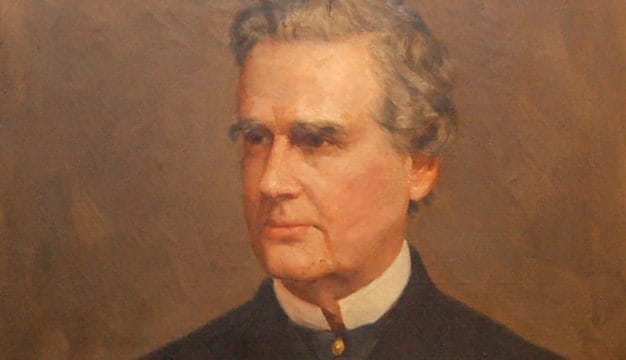

William Crawford Gorgas (1854-1920) was a pioneer in the field of public health and tropical medicine. His work in eradicating yellow fever in Panama made possible the construction of the Panama Canal. Gorgas served as U.S. Army surgeon general, received honorary degrees from seven different universities, won honors from several foreign countries for his service to public health, and fought tirelessly to improve sanitary conditions throughout South America and Africa.

Gorgas, William Crawford

William Crawford Gorgas (1854-1920) was a pioneer in the field of public health and tropical medicine. His work in eradicating yellow fever in Panama made possible the construction of the Panama Canal. Gorgas served as U.S. Army surgeon general, received honorary degrees from seven different universities, won honors from several foreign countries for his service to public health, and fought tirelessly to improve sanitary conditions throughout South America and Africa.

Gorgas was born on October 3, 1854, in Toulminville, near Mobile, Alabama, at the home of his grandfather John Gayle, a former governor of Alabama. His parents were Amelia Gayle Gorgas, born in Greensboro, Hale County, and Josiah Gorgas, a U.S. Army lieutenant and commandant of the Mount Vernon Arsenal who was born in Running Pumps, Pennsylvania. The Gorgases lived in Mount Vernon until mid-1856 and then moved to various arsenal locations in Maine, South Carolina, and Pennsylvania. In 1861, Josiah received an appointment as chief of ordnance for the Confederacy. He relocated to Richmond, Virginia, with the rest of the Confederate government in June 1862, and his family joined him soon thereafter. When Josiah fled Richmond with the Confederate government in April 1865, his family, which by this time included William Crawford’s sisters Jessie, Mary Gayle, Christine Amelia, and Maria Bayne and brother, Richard Haynsworth, moved in with Amelia’s sister in Richmond. Later that year, the two sisters and their children moved to Maryland.

In 1866, Josiah Gorgas and several other investors reopened an existing iron works at Brierfield, Alabama, and his family joined him there. The years in Brierfield were happy for the family, and young William Crawford fished, hunted, and rode horseback, activities that he enjoyed throughout his life. And despite his father’s vehement opposition, the young Gorgas dreamed of a military career.

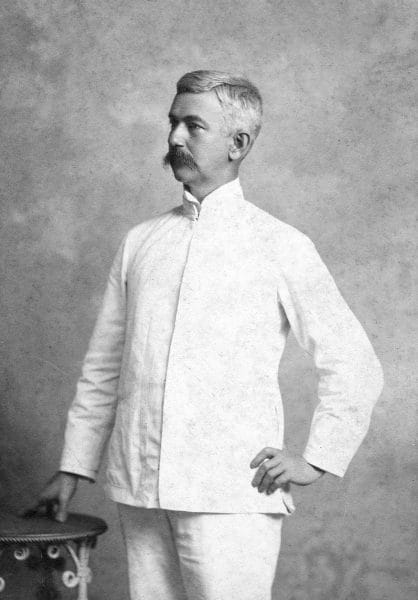

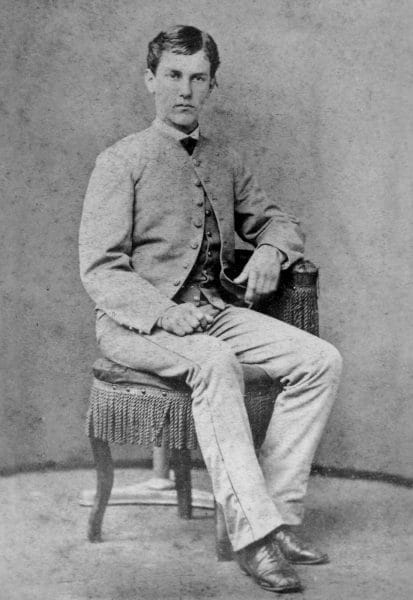

Gorgas at Sewanee

The iron works failed in 1869, and Josiah Gorgas took a position as headmaster at the University of the South at Sewanee, Tennessee, set in a remote, mountain-top wilderness and populated largely by ex-Confederates. Gorgas accompanied his father, attended the university, and graduated in 1875. Gorgas then spent an unhappy year in his uncle’s New Orleans law office. He was determined to follow his father into the U.S. Army, but he failed to get into West Point and instead enrolled in medical school at Bellevue Hospital Medical College in New York City, graduating in 1879. He interned at Bellevue and at the New York Insane Asylum at Blackwell’s Island, New York, before entering the U.S. Army Medical Corps in June 1880 as a first lieutenant.

Gorgas at Sewanee

The iron works failed in 1869, and Josiah Gorgas took a position as headmaster at the University of the South at Sewanee, Tennessee, set in a remote, mountain-top wilderness and populated largely by ex-Confederates. Gorgas accompanied his father, attended the university, and graduated in 1875. Gorgas then spent an unhappy year in his uncle’s New Orleans law office. He was determined to follow his father into the U.S. Army, but he failed to get into West Point and instead enrolled in medical school at Bellevue Hospital Medical College in New York City, graduating in 1879. He interned at Bellevue and at the New York Insane Asylum at Blackwell’s Island, New York, before entering the U.S. Army Medical Corps in June 1880 as a first lieutenant.

Gorgas’s years in medical school coincided with his father’s failing health and threats of dismissal from Sewanee trustees. The family’s grim financial state led all of his siblings to quit school and find employment to contribute to the family’s income. Gorgas’s father was no longer able to supplement his income, and his already frugal lifestyle became even more frugal. In 1881, he began sending money to his family monthly, a practice he continued until suffering a stroke in 1920.

Between 1880 and 1884 Gorgas served at army posts in south Texas, where he contracted a mild case of yellow fever. While convalescing, he met Marie Doughty, another fever victim. The two married in September 1885 and had one daughter, Aileen Lyster, in 1889. In late 1885, Gorgas was assigned to Fort Randall, North Dakota, where he made house calls wrapped in buffalo robes in frigid temperatures and blizzards. He was promoted to captain in 1885. Because he now was immune to yellow fever, he next served two tours of duty from 1888 to 1898 at Fort Barrancas, in Pensacola, Florida, where he successfully controlled a yellow fever epidemic.

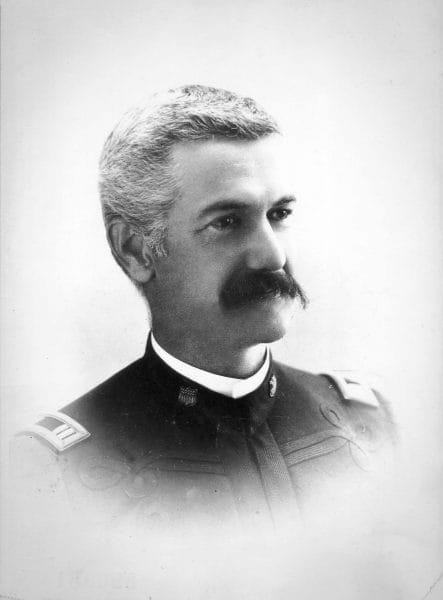

William Crawford Gorgas in Uniform

Promoted to major, Gorgas became chief sanitary officer for U.S.-occupied Havana, Cuba, in July 1898. He instituted strict sanitation codes that led to the decline of other diseases in the city, but yellow fever occurrences continued to rise. Gorgas rejected the theory that mosquitoes transmitted yellow fever until 1900, when fellow Army physician Maj. Walter Reed proved that the female Stegomyia (now known as the Aedes) mosquito spread the disease. Gorgas soon implemented efforts to destroy mosquito breeding sites, and by September 1901 these procedures had eliminated yellow fever in the Havana area. Gorgas became enormously popular among Havana’s citizens.

William Crawford Gorgas in Uniform

Promoted to major, Gorgas became chief sanitary officer for U.S.-occupied Havana, Cuba, in July 1898. He instituted strict sanitation codes that led to the decline of other diseases in the city, but yellow fever occurrences continued to rise. Gorgas rejected the theory that mosquitoes transmitted yellow fever until 1900, when fellow Army physician Maj. Walter Reed proved that the female Stegomyia (now known as the Aedes) mosquito spread the disease. Gorgas soon implemented efforts to destroy mosquito breeding sites, and by September 1901 these procedures had eliminated yellow fever in the Havana area. Gorgas became enormously popular among Havana’s citizens.

That same year, the U.S. government began planning for the construction of the Panama Canal and named Gorgas as the sanitary expert for the project. He spent 1902 preparing for the assignment by familiarizing himself with the failed French attempts to construct a canal in Panama and by touring the Suez Canal in Egypt and the proposed site of the canal in Panama. When the government created a commission to lead the canal project, the American Medical Association tried unsuccessfully to place Gorgas on the commission. He thus found himself answering to a frugal commission that dismissed the mosquito theory.

Gorgas was promoted to colonel in March 1903 and sailed for Panama in June 1904. Despite Gorgas’s knowledge of the area and its disease potential, the head of the commission routinely refused to approve the doctor’s requisitions for supplies. Gorgas faced local officials unwilling to enforce sanitary regulations for fear of losing elections, U.S. officials opposed to the mosquito theory, and stingy Washington bureaucrats convinced that sanitation money could be better spent on other aspects of canal construction. As Gorgas’s predictions about sanitary conditions came to pass and controversy mounted over the canal’s slow progress, the American Medical Association sent an eminent surgeon to determine the truth about conditions. The resulting report condemned the commission for abuses of authority, delays in acquisition of urgently needed supplies, and deliberate obstruction of canal work. Gorgas, however, received warm praise.

In early 1905, Pres. Theodore Roosevelt read the report and decided to replace the commission members, reorganize the sanitary department, and replace Gorgas. The dean of the Johns Hopkins Medical School in Baltimore, Maryland, advised Roosevelt that no one was as qualified as Gorgas in the sanitation field, however, and Roosevelt promised to retain Gorgas and to support his work. In mid-1905, Roosevelt appointed a new chief engineer who believed in the mosquito theory and supported Gorgas. The subsequent two years were “halcyon days,” as Gorgas described them. The sanitary department in Panama accomplished more than at any other time in the construction of the canal, and yellow fever cases took a steep decline. In November 1906 Roosevelt visited the canal, praised Gorgas’s work, reorganized the canal administration, and made the sanitary department responsible only to the chairman of the canal commission.

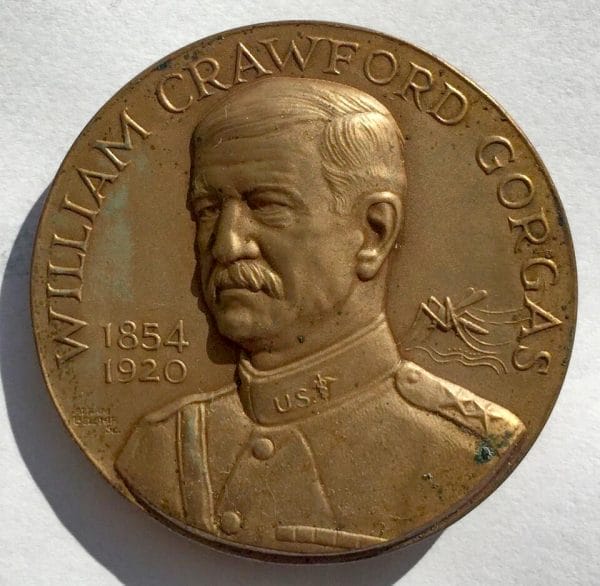

Gorgas Panama Medal

Unfortunately, this favorable period ended in 1907 with the appointment of still another chief engineer and commission chairman, George W. Goethals, a man who issued orders and viewed disagreement as disloyalty. Gorgas had won cooperation from the Panamanians and canal employees through charm and salesmanship. Now he found himself reporting to a man who did not believe in his sanitation program, was bitterly hostile to him personally, and ruled the construction project like a dictator.

Gorgas Panama Medal

Unfortunately, this favorable period ended in 1907 with the appointment of still another chief engineer and commission chairman, George W. Goethals, a man who issued orders and viewed disagreement as disloyalty. Gorgas had won cooperation from the Panamanians and canal employees through charm and salesmanship. Now he found himself reporting to a man who did not believe in his sanitation program, was bitterly hostile to him personally, and ruled the construction project like a dictator.

Despite his difficult working conditions, Gorgas began to receive wide recognition for his accomplishments. In 1908 he was elected president of the American Medical Association, and in 1911 he was offered the presidency of the University of Alabama, which he considered his highest honor. Believing his duty was to see the Panama Canal project through to completion, he regretfully declined the offer.

By the time the canal opened to commercial traffic in August 1914, Gorgas had taken a leave of absence and was consulting about sanitation and other health issues in Africa. In January 1914, he received a promotion to brigadier general and an appointment as U.S. Army surgeon general; promotion to major general followed in March 1915. In mid-1916, the Rockefeller Foundation asked him to consult on yellow fever in Central and South America, where he was welcomed as a hero.

That same year, Gorgas became occupied with preparations for potential U.S. involvement in World War I. After mobilization began, disease and deaths in army camps followed. Gorgas personally inspected camps and found them too overcrowded for good sanitation. In addition, his superiors were willing to construct and equip every type of building except hospitals. His successful efforts to rectify these conditions broke the pattern of previous wars, in which more deaths had resulted from disease than from bullets. Gorgas retired from the army on October 3, 1918.

Not long afterward, Gorgas returned to South America, at the request of the Rockefeller Foundation’s International Health Board, to address persistent pockets of yellow fever. In 1920, he traveled to Europe and Africa and then to London, where he suffered a stroke. At Queen Alexandra Military Hospital, Gorgas received a visit from King George V, who knighted him. Gorgas’s condition worsened, however, and he died on July 3, 1920.

Following a funeral at St. Paul’s Cathedral, a full military cortege, including Coldstream Guards playing Chopin’s Funeral March, processed through the streets of London. Gorgas’s family transported his body back to the United States, where it lay in state for four days at Washington’s Church of the Epiphany. Burial followed at Arlington National Cemetery. In 1993, the American Society of Tropical Medicine & Hygiene created the Gorgas Memorial Institute Research Award, also known as the Gorgas Panama Award, for efforts to advance global health, especially in the field of tropical diseases. The organization ceased the award in 2014.

Further Reading

- Gibson, John M. Physician to the World: The Life of General William C. Gorgas. 1950. Reprint, Tuscaloosa, Al.: University of Alabama Press, 1989.

- Gorgas, Marie D., and Burton J. Hendrick. William C. Gorgas: His Life and Work. Garden City, N.Y.: Garden City Publishing, l924.

- Gorgas, William Crawford. Sanitation in Panama. New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1915.

- Wiggins, Sarah Woolfolk. Love and Duty: Amelia and Josiah Gorgas and Their Family. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2005.